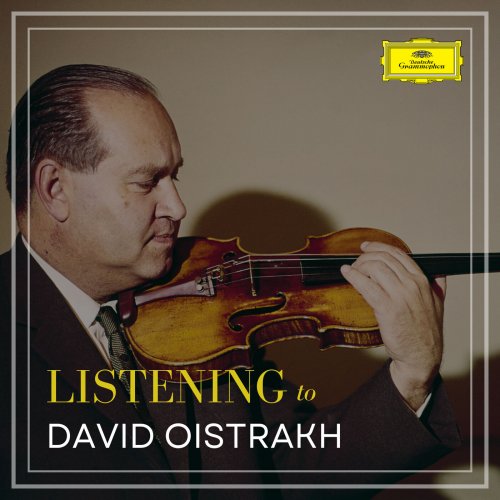

David Oistrakh - Listening to David Oistrakh (2022)

Artist: David Oistrakh, Igor Oistrakh, Vladimir Yampolsky, Hans Pischner, Lev Oborin, Kirill Kondrashin, Eugène Goossens

Title: Listening to David Oistrakh

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: UMG Recordings, Inc.

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 8:45:15

Total Size: 2.12 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Listening to David Oistrakh

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: UMG Recordings, Inc.

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 8:45:15

Total Size: 2.12 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. No. 4 in A Minor

02. I. Allegro moderato

03. 1. Allegro

04. No. 5 in E Major

05. I. Adagio

06. Sarasate: Navarra for Two Violins, Op. 33

07. I. Vivace

08. III. Andante espressivo - attacca

09. Paganini: Variations On The G String On A Theme From Rossini's "Moses"

10. I. Allegro

11. 3. Allegro

12. No. 5 In E Major

13. II. Largo

14. 3. Alla breve

15. No. 2

16. 3. Allegro

17. IV. Vivace

18. No. 3

19. Kreisler: La Gitana

20. 1. Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord No. 5 in F Minor, BWV 1018

21. Sarasate: Zortzico (Spanish Dance)

22. 1. Vorspiel (Allegro moderato)

23. IV. Allegro

24. III. Adagio

25. 1. Moderato

26. III. Allegro

27. IV. Presto

28. III. Adagio

29. Ravel: Tzigane

30. III. Finale (Allegro vivacissimo)

31. 4. Presto

32. I. Adagio

33. 3. Vivace giocoso

34. 1. Andante - Allegro

35. No. 2 in E Flat Major

36. III. Allegro

37. 2. Largo

38. 1. Adagio

39. 2. Allabreve

40. III. Allegro assai

41. II. Allegro

42. II. Allegro

43. I. Allegro

44. V. Allegro

45. IV. Allegro

46. 2. Arioso

47. 2. Andante - Tempo I

48. III. Andante un poco

49. 2. Scherzo. Vivacissimo

50. III. Allegro assai

51. 3. Allegro

52. 1. Allegro molto e con brio

53. IV. Allegro

54. III. Andante

55. Beethoven: Violin Romance No. 2 in F Major, Op. 50

56. 1. Adagio

57. II. Allegro

58. 3. Allegro

59. II. Andante

60. 2. Adagio

61. I. Siciliano (Largo)

62. III. Finale (Presto)

63. 1. Andantino

64. II. Adagio

65. 3. Allegretto - Allegro molto vivace

66. 2. Andantino cantabile

67. III. Adagio ma non tanto

68. 1. Moderato

69. 3. Finale (Allegro energico)

70. II. Canzonetta (Andante)

71. IV. Adagio

72. II. Allegro

73. 2. Larghetto

74. II. Adagio

75. Beethoven: Violin Romance No. 1 in G Major, Op. 40

76. III. Allegro risoluto - Allegro molto - Tempo rubato - Moderato - Meno mosso - Moderato

77. II. Andante

78. II. Largo ma non tanto

79. Glazunov: Mazurka-Oberek

80. IV. Finale. Allegro con brio

81. II. Allegro molto - Tema con variazioni

82. 2. Andante

83. Wieniawski: Legende, Op. 17

84. 3. Moderato

85. III. Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace - Poco più presto

86. I. Allegro

87. 1. Allegro molto appassionato

88. I. Allegro

89. Ysaÿe: Poeme Elegiaque, Op. 12

90. Chausson: Poème, Op. 25

David Oistrakh is considered the premiere violinist of mid-20th century Soviet Union. His recorded legacy includes nearly the entire standard violin repertory up to and including Prokofiev and Bartók. Oistrakh's violin studies began in 1913 with famed teacher Pyotr Stolyarsky. Later he officially joined Stolyarsky's class at the Odessa Conservatory, graduating in 1926 by playing Prokofiev's First Violin Concerto. Performances of the Glazunov concerto in Odessa and Kiev in 1927, and a 1928 debut in Leningrad (Tchaikovsky concerto), gave Oistrakh the confidence to move to Moscow. He made his premiere there in early 1929, but the event went largely unnoticed. In 1934, however, after several years of patiently refining his craft, Oistrakh was invited to join the Moscow Conservatory, eventually rising to the rank of full professor in 1939.

Meanwhile, Oistrakh was gaining success on the competition circuit, winning the 1930 All-Ukrainian contest, and the All-Soviet competition three years later. In 1935 he took second prize at the Wieniawski competition. In 1937 the Soviet government sent the now veteran violinist to Brussels to compete in the International Ysaÿe Competition, where he took home first prize.

With his victory in Brussels, Soviet composers began to take notice of their young compatriot, enabling Oistrakh to work closely with Myaskovsky and Khachaturian on their concertos in 1939 and 1940, respectively. In addition, his close friendship with Shostakovich led the composer to write two concertos for the instrument (the first of which Oistrakh played at his, and its, triumphant American premiere in 1955). During the 1940s Oistrakh's active performing schedule took him across the Soviet Union but his international career had to wait until the 1950s, when the political climate had cooled enough for Soviet artists to be welcomed in the capitals of the West.

The remaining decades of Oistrakh's life were devoted to maintaining the highest possible standards of excellence throughout an exhausting touring schedule (he returned to the U.S. six times in the 1960s), and he began a small but successful sideline career as an orchestral conductor. His death came suddenly in Amsterdam in 1974, during a cycle of Brahms concerts in which he both played and conducted. Oistrakh's unexpected death left a void in the Soviet musical world which was never really filled.

Throughout his career David Oistrakh was known for his honest, warm personality; he developed close friendships with many of the leading musicians of the day. His violin technique was virtually flawless, though he never allowed purely physical matters to dominate his musical performances. He always demanded of himself (and his students) that musical proficiency, intelligence, and emotion be in balance, regardless of the particular style. Oistrakh felt that a violinist's essence was communicated through clever and subtle use of the bow, and not through overly expressive use of vibrato. To this end he developed a remarkably relaxed, flexible right arm technique, capable of producing the most delicate expressive nuances, but equally capable of generating great volume and projection.

As a teacher, David Oistrakh maintained that a teacher should do no more than necessary to help guide the student toward his or her own solutions to technical and interpretive difficulties. He rarely played during lessons, fearing that he might distract the student from developing a more individual approach, and even encouraged his students to challenge his interpretations. Perhaps the best evidence of the Oistrakh's gift for teaching is that he felt that he gained as much from the teaching experience as his students did. ~ Blair Johnston

Meanwhile, Oistrakh was gaining success on the competition circuit, winning the 1930 All-Ukrainian contest, and the All-Soviet competition three years later. In 1935 he took second prize at the Wieniawski competition. In 1937 the Soviet government sent the now veteran violinist to Brussels to compete in the International Ysaÿe Competition, where he took home first prize.

With his victory in Brussels, Soviet composers began to take notice of their young compatriot, enabling Oistrakh to work closely with Myaskovsky and Khachaturian on their concertos in 1939 and 1940, respectively. In addition, his close friendship with Shostakovich led the composer to write two concertos for the instrument (the first of which Oistrakh played at his, and its, triumphant American premiere in 1955). During the 1940s Oistrakh's active performing schedule took him across the Soviet Union but his international career had to wait until the 1950s, when the political climate had cooled enough for Soviet artists to be welcomed in the capitals of the West.

The remaining decades of Oistrakh's life were devoted to maintaining the highest possible standards of excellence throughout an exhausting touring schedule (he returned to the U.S. six times in the 1960s), and he began a small but successful sideline career as an orchestral conductor. His death came suddenly in Amsterdam in 1974, during a cycle of Brahms concerts in which he both played and conducted. Oistrakh's unexpected death left a void in the Soviet musical world which was never really filled.

Throughout his career David Oistrakh was known for his honest, warm personality; he developed close friendships with many of the leading musicians of the day. His violin technique was virtually flawless, though he never allowed purely physical matters to dominate his musical performances. He always demanded of himself (and his students) that musical proficiency, intelligence, and emotion be in balance, regardless of the particular style. Oistrakh felt that a violinist's essence was communicated through clever and subtle use of the bow, and not through overly expressive use of vibrato. To this end he developed a remarkably relaxed, flexible right arm technique, capable of producing the most delicate expressive nuances, but equally capable of generating great volume and projection.

As a teacher, David Oistrakh maintained that a teacher should do no more than necessary to help guide the student toward his or her own solutions to technical and interpretive difficulties. He rarely played during lessons, fearing that he might distract the student from developing a more individual approach, and even encouraged his students to challenge his interpretations. Perhaps the best evidence of the Oistrakh's gift for teaching is that he felt that he gained as much from the teaching experience as his students did. ~ Blair Johnston

Related Releases:

Listening to Grieg

Listening to Dvořák

Listening to Bruckner

Listening to Béla Bartók

Listening to Shostakovich

Listening to Arnold Schoenberg

Listening to Gustav Holst and more

Listening to Grieg

Listening to Dvořák

Listening to Bruckner

Listening to Béla Bartók

Listening to Shostakovich

Listening to Arnold Schoenberg

Listening to Gustav Holst and more

![Tim Kliphuis, Maya Fridman, Marc van Roon - Kosmos (2025) [Hi-Res] Tim Kliphuis, Maya Fridman, Marc van Roon - Kosmos (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765893448_folder.jpg)