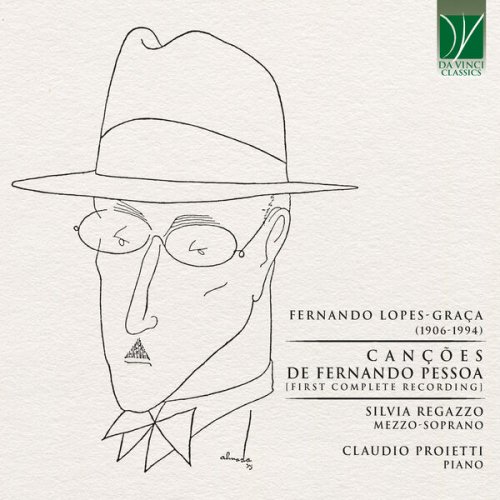

Artist:

Silvia Regazzo, Claudio Proietti

Title:

Fernando Lopes-Graça: Cançōes de Fernando Pessoa (First Complete Recording)

Year Of Release:

2022

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 1:07:42

Total Size: 237 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:01. Duas canções de Fernando Pessoa, LG 163: No. 1, Põe-me as mãos nos ombros

02. Duas canções de Fernando Pessoa, LG 163: No. 2, Sol nulo nos dias vãos

03. O menino da sua mãe, LG 167

04. Três canções de Fernando Pessoa, LG 179: No. 1, Cavalo de sombra, cavaleiro monge

05. Três canções de Fernando Pessoa, LG 179: No. 2, Horizonte

06. Três canções de Fernando Pessoa, LG 179: No. 3, Não sei se é sonho, se realidade

07. Tomámos a vila depois de um intenso bombardeamento, LG 221

08. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 1, Coroai-me de rosas

09. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 2, Aqui, dizeis …

10. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 3, Ao longe os montes …

11. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 4, Bocas roxas de vinho

12. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 5, Já sobre a fronte vã …

13. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 6, Olho os campos, Neera …

14. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 7, O ritmo antigo …

15. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 8, O mar jaz …

16. Nove odes de Ricardo Reis, LG 242: No. 9, O deus Pã não morreu

17. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 1, Velo, na noite em mim …

18. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 2, Há luz no tojo e no brejo

19. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 3, Há quanto tempo não canto

20. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 4, Cheguei à janela …

21. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 5, Dorme criança, dorme

22. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 6, Sopra o vento, sopra o vento

23. Cantos de mágoa e desalento, LG 243: No. 7, Um dia baço …

24. Quatro momentos de Álvaro de Campos, LG 244: No. 1, Dá-me lírios, lírios

25. Quatro momentos de Álvaro de Campos, LG 244: No. 2, De la musique

26. Quatro momentos de Álvaro de Campos, LG 244: No. 3, Trapo

27. Quatro momentos de Álvaro de Campos, LG 244: No. 4, Magnificat

The music conceived by Fernando Lopes-Graça, who certainly was one of the most important Portuguese composers of the twentieth century, is a wide and multifaceted universe. And also a very complex one.

It is the meta-historical heritage of his life, which was lived with an exemplary rigour and engagement in every form of its manifestations: in ethnomusicology, in the form of cultural promotion, as organisation of musical events, as popularisation, as essay-writing, as concert activity, and as political engagement.

These all are the fields in which Lopes-Garça worked, representing an essential and safe reference point for his contemporaries. He was always led, staunchly and without doubts, by his deep faith in the communist idea.

If one considers that Lopes-Graça was only 26 years old when a fascist dictatorship came into power in Portugal, keeping a firm grip on it until 1974, it can easily be understood that this political choice brought to his life enormous limitations, persecutions, and professional ostracism by the public institutions, and at times even imprisonment.

Indeed, the compelling need he felt for the definition of his own musical language, which had to be in line with contemporaneous European trends (Lopes-Graça called Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Bartók the “cornerstones of modern musical thought”) caused him, at certain points, some problems also with the Portuguese Communist Party. Its most orthodox members rigidly followed the anti-formalist (and therefore anti-modernist) dictates which Ždanov had imposed in the USSR.

Still, Lopes-Graça went straight down his own path. His entire, vast output is all woven with the thread of modernity – as concerns his aesthetic, poetic, and linguistic thought – along with that of a non-renounceable political and ethical engagement.

Within his output, his songs for voice and piano occupy a relevant place, reaching the considerable size of nearly 550 pieces. Many of them have a folklike inspiration, and derive from the profound ethnomusicological research made by the composer following his on-field campaigns in various regions of Portugal. The intimately archaic and pre-tonal features of the peasants’ songs became, little by little, the nourishment for his own creative experience, thus deeply contributing to the definition of its modernity.

Still, many of his songs set to music the lyrics of the greatest Portuguese poets who lived from the sixteenth century onwards, and in particular Antero de Quental (1842-1891). The highest importance, however, is given to the composer’s contemporaries, among whom tens and tens of different names are found. It is as if Lopes-Graça intended to play a systematic role in bearing witness to his own epoch. The names of Adolfo Casais Monteiro and José Régio are significant among the representatives of the modernist trend; in the field of neo-realism, those of José Gomes Ferreira and Carlos de Oliveira stand out. Finally we reach the pre-eminent names of Eugénio de Andrade, and obviously, José Saramago, by whom Lopes-Graça set to music a Tríptico de D. João in 1993.

However, doubtlessly the most intense and fecund relationship was that between the composer and the poetry by Fernando Pessoa: from it, twenty-seven works came to being. However, they are found in a rather inhomogeneous fashion within the chronology of Lopes-Graça’s works: three in 1934/36, three in 1947/50, one in 1960, and no less than twenty in 1989.

From a close observation, it results that this temporal discontinuity corresponds to a thematic separation, mirrored in turn by musical writing, in such a fashion that it probably goes beyond the composer’s overall stylistic evolution. It is certainly not by chance that among the first compositions, and along with eternally Pessoan themes (such as the indefinable boundary between dream, illusion, and reality, or the sense of extraneity with respect to being) there are also others, which as much more seldom found, such as the terrible denunciation of war (O menino da sua mãe, Tomámos a vila depois de um intenso bombardeamento), or else fantastic images from nightmares (Cavalo de sombra, cavaleiro monge).

In all cases, the first songs are all works with a great expressivity and a solid modernity, even though they are bound to linguistic and formal traits which are very easy to identify even at first hearing (key, strophic structure, a kind of descriptive adhesion to the images created by the verses, even when they slide into the dreamy). They are essential and very well-defined works, depicting true aural narratives, needing wide temporal spaces in order to take shape.

The great flowering of songs on Pessoa’s lyrics in 1987 was caused by an external fact. In 1988 the poet’s hundredth birthday was to be celebrated. The Portuguese Ministry of Culture asked Lopes-Garça to participate in the festivities. Thus no less than three different cycles were created: the Nove odes de Ricardo Reis (completed on March 8th, 1987), the Cantos de mágoa e desalento (composed just nineteen days after, on March 27th), and the Quatro momentos de Álvaro de Campos (written between October 24th and November 21st).

This is a true immersion within the poetic world of Pessoa and of his heteronyms; an aesthetic rapture and, at the same time, a great and complex project. That project aimed at musically retracing some of the numerous, and frequently ungraspable, lines of the poet’s multiple personalities. Thus three series of pieces came to being; like splinters from a broken mirror, they offer disconnected fragments of reality and dream. They do so by drawing fleeting melodies, by employing crude and elusive harmonies, by evoking symbolic rhythms and gestures. They do so by creating true musical metaphors, which constantly avoid the definition of shapes and boundaries, and often even that between piano and voice, which are merged with another in a single expressive epiphany. At the end, every song remains suspended over mute and eternal questions. It seems to gaze beyond, with a blind person’s empty eyes.

According to tradition, Homer was blind just as Demodocus, the aoidos in Alcynoo’s house. Pessoa was very short-sighted: on his deathbed, he requested his glasses, perhaps in order to see for a last time that world in which he had never learnt to live. In antiquity, blindness was the seer’s prerogative, a trait of those who had no access to the shared reality, but rather to a superior one. Pessoa hid to most people his identity as an author, and was a professional translator – more precisely, he was a “correspondent in foreign language of commercial enterprises”. He had spent most of his youthful years in South Africa, and therefore he studied and thought in English. Portuguese, instead, was the language of his heteronyms: Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis – to cite at least those appearing in the titles of Lopes-Graça’s song collections.

“Today I have no personality: I have divided all my humanness among the various authors whom I’ve served as literary executors. Today I am the meeting-place of a small humanity that belongs only to me. Being the medium of myself, still I subsist”. So did Pessoa write in The Genesis of the Heteronyms, a book collecting countless prose fragments he wrote during the course of his life, offering us a valuable interpretive key in order to define the timbre of his many voices.

Lopes-Graça did not compose a music which “accompanies” Pessoa’s poetry, but rather gave a voice to those many voices. It is for this reason that, from one collection to another, it seems that we are listening to different composers, and it is hard to believe that such heterogeneous atmospheres can refer to the same hand. Lopes-Graça followed in Pessoa’s footsteps, choosing to hide the one and to give voice to the others, to hide as the One and to give body to the Other.

Thus, it is the sounds of the Portuguese language, as they came out from the poietés’s pen (the poet-creator in the Greek meaning of the term) that create the melodies and harmonies by which Lopes-Graça’s score is composed. Sound is not superscripted, but rather found inside the word of Pessoa’s heteronyms, who tell reality and evoke atmospheres on the basis of their diverse identities. His lines are simply “let sing”; they are threads artfully intertwined by a composer who becomes one with the thread itself, and who allows a subtle and changing fabric to materialize under his fingers, woven in darkness by several hands, by several names.

We believe that, in the modern era, a comparable unity of meaning between poetic word and music was hardly ever achieved.

Silvia Regazzo, Claudio Proietti © 2022

![Demo Rumudo - Second Nature (2025) [Hi-Res] Demo Rumudo - Second Nature (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765883076_cover.jpg)