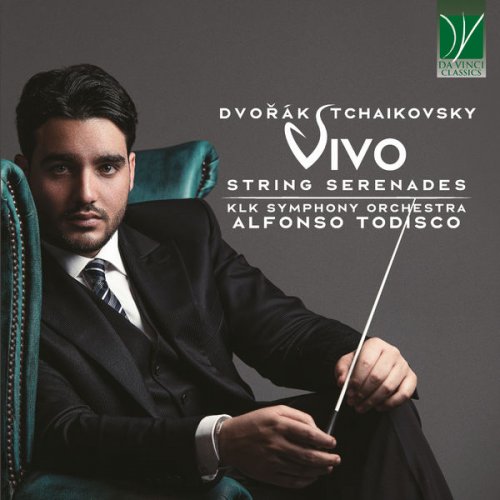

Artist:

Alfonso Todisco, Klk Symphony Orchestra

Title:

Dvorak, Tchaikovsky: Vivo, String Serenades

Year Of Release:

2022

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 59:41

Total Size: 294 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:01. Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22: I. Moderato

02. Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22: II. Tempo di Valse

03. Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22: III. Scherzo. Vivace

04. Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22: IV. Larghetto

05. Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22: V. Finale. Allegro vivace

06. Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48: I. Pezzo in forma di Sonatina

07. Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48: II. Walzer

08. Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48: III. Elégie

09. Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48: IV. Finale. Tema Russo

I imagine Dvořák and Tchaikovsky, at dusk, reflecting on their itinerary, on their art, on their life.

I imagine a moved Dvořák, having in his arms his firstborn, only a few months old, and with a luminous future before him. A prestigious award had recently changed his life; enthusiasm gets mixed with fear, and the true challenge of maturity begins.

I imagine Tchaikovsky alone, immersed in himself, tormented by a personal and creative crisis. He is seeking refuge in music; he lets his heart lead him. Probably that is the road, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. From that moment onwards, a spiritual rebirth will lead him to the apex of his career.

In music I love to read images and suggestions which are certainly personal, but inspired by a careful study of the composers’ lives at the time when they created their works. The music of these two masterpieces is living, rich in nuances, dense with emotionality, the fruit of an expressive research that the composers were living in a period of transition in their life. The free character of the “Serenade” is the perfect creative space for the two Romantic composers’ musical reflections. Between intimism and virtuosity, they gave life to true “artist’s pictures”, whereby it is easy to get lost, with closed eyes, in a mystical dialogue between dream and reality. Music, with a typically Romantic flavour, is “alive”, intense, evocative of images. One needs to listen just to the few initial bars in order to understand that it is a deeply inspired music.

Alfonso Todisco © 2022

The string orchestra is a very ancient and noble ensemble. Indeed, it is one of the earliest examples of “orchestra” in the Western tradition, if one considers the ensemble of viols typical for the English Renaissance as a string orchestra. In the Baroque era, string orchestras were called to the fore by many musicians, most notably in the Italian tradition (Vivaldi towering among them). In those cases, however, the strings were normally supported by a continuo part played by keyboards or other continuo instruments. In the Classical and early Romantic era, there are certainly significant examples of music for string orchestra, particularly chamber symphonies and, as we will see, Serenades, but most orchestral music is scored for orchestras with the presence of winds and at times percussions. Of course, the timbral variety provided by the great family of the winds is an extraordinary creative opportunity for a composer, one which is not easily renounced. At the same time, however, the greater homogeneity of a string ensemble is not without its own value, nor does it equal timbral flatness. Whilst bowed string instruments belong in the same instrumental family, their timbre is by no means the same – one simply needs to hear two notes by the same pitch played by a violin and by a cello and the difference is immediately evident. Moreover, a vast palette of timbral effects and nuances is available to composers writing for strings, including (most evidently) pizzicatos or con sordino, but also a plethora of different sounds created through different uses of the bow or of vibrato.

From a certain viewpoint, therefore, one could say that writing for a string orchestra can be not “just” an artistic undertaking in itself, but also a kind of compositional exercise. The relative limitation of the expressive resources available to the composer – in comparison with a full symphony orchestra – may prompt a very refined work on the nuances, shades, and light colours which can be chosen.

And this is certainly what both Antonín Dvořák and Pëtr Il’ič Tchaikovsky did with their two Serenades for strings.

They were written within the space of five years: Dvořák’s dates from 1875 and Tchaikovsky’s from 1880. Dvořák was 34 years old when he wrote this masterpiece, whilst Tchaikovsky had turned forty; the two composers were born respectively in 1841 and 1840. They were both living a delicate period in their lives: a moment of gradual resurrection, in Tchaikovsky’s case, and a moment of euphoria in Dvořák’s, whose life (contrary to Tchaikovsky’s) looked promising and rosy. But these biographical details are not all the two had in common. For both, one of the most pressing issues, as concerns the quest for their compositional style, was the need to find a voice of their own, particularly as concerns the relations between Eastern and Western Europe in musical terms.

Nineteenth-century instrumental music was dominated by the Austro-German tradition, just as coeval opera was mainly the domain of Italian musicians. There were, however, many other national schools striving for recognition. Politics, of course, was not entirely outside the scope of artistic inspiration. The Austro-Hungarian empire was, in its own fashion, an almost miraculous mosaic of different national and ethnic identities; still, virtually all the peoples which were subjugated by the Habsburg crown felt this yoke as oppressive. And the expansionist politics of Germany and Prussia was not looked upon favourably by their neighbours either. Whilst they admired the undeniable genius of the Austrian and German masters (such as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, and then Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, etc.), they were rather reluctant to simply submit their style to the (implicit) dictates of the German-speaking composers.

Russia, of course, was politically distinct, having an empire of its own. But here too there was a difficult balance to be sought between the Russians’ fascination for the West (this was the time when the educated Russians spoke French with each other) and the equally powerful attraction for national roots.

In Russia, this was the time when the Mighty Five tried and realised a genuinely “national” music, grounded on the musical tradition and roots of their homeland. But Tchaikovsky did not adhere to their principles. There is plenty of “Russia” also in his own music, to be sure; one clear example is also found in the Finale of the Serenade recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. But it is a kind of tamed Russia, a Russia politely exotic and enough (but not too much) colourful. On the other hand, the Mighty Five were not afraid to present some of the disconcerting features of the Russian musical tradition, such as the use of complex rhythms or of ancient modes.

Dvořák, in turn, came from an extremely ancient and august musical background. Bohemia and Czechia certainly qualify as one of the most musical zones of Europe, and have earned this reputation thanks to centuries of high-level music-making. Dvořák himself was the child of a butcher and helped his father both in his butchery and in the attached inn; yet, as all children of his nation, young Antonín was educated in music, and this allowed his extraordinary talent to come to the fore.

Dvořák’s accomplishment was first recognised by the Germans, though; precisely at the time of the Serenade’s composition he won a fellowship, awarded by such German-speaking authorities as Johannes Brahms and Eduard Hanslick, which definitively launched his career in the West. Doubtlessly, Dvořák’s style owes much to Brahms and to the Western tradition, but equally doubtlessly he constantly strove in order to integrate it with the expression of a genuinely national vein. By way of contrast, Tchaikovsky was not at all afraid of admitting the importance of Mozart’s influence on his own style, even though the century dividing Mozart from him dug an abyss in terms of musical language. Indeed, the Serenade recorded in this CD was acknowledged by Tchaikovsky as being directly inspired by Mozart’s Serenades for strings, to the point of mimicking their structure, and of “updating” the presence of a triple-time dance (a Minuet, in Mozart’s serenades) to a “modern” dance typical of his own time (a Waltz, which would become one of the most famous movements of this work, also thanks to George Balanchine’s memorable choreography).

A Waltz is also present in Dvořák’s Serenade, where it is found as the second movement, and evokes the genuine atmospheres of the dancing room, where the composer had worked as an orchestra violinist to earn his living. It follows the opening movement, a Moderato whose musical concept is broad and generous, suggesting the vast atmospheres of Dvořák’s homeland. After the Tempo di Valse, Dvořák inserts a hectic Scherzo, where both the freshness of his inspiration and his absolute mastery of contrapuntal techniques appear clearly. Polyphony is not seen as a learned device, here, but rather as a means for layering the musical texture in such a fashion that the result becomes thrilling and enthralling.

At the heart of Dvořák’s Serenade is certainly the magnificent Larghetto, whose beauty actually extends to the other movements, which occasionally cite its enchanted melodies. The expressive intensity of this slow movement is turned into unrestrained liveliness in the closing movement, rivalling with Tchaikovsky’s Finale in terms of vivacity and brilliance.

Tchaikovsky’s composition opens with a meditative chorale, employed as an introduction, but whose importance will be fully revealed at the work’s closing. The first movement is a “sonatina”, but the label is an understatement, since it is a fully-fledged Sonata form. At its end, we find a first return of the opening chorale. After the famous waltz there comes the touching and moving Elegy, whose lyrical depth certainly stands comparison with Dvořák’s Larghetto. The fourth and last movement is built on a Russian (or rather Russian-sounding!) folk dance, whose pace becomes mind-numbing in the Coda… but not without a welcome moment of respite, surprisingly cast as a quotation of the opening, introductory Chorale.

Together, these two masterpieces represent a fascinating diptych which reveals us the full potential and the rich palette of the Romantic string orchestra, as well as the reciprocal enrichment of the Western and Eastern musical traditions when they enter a fruitful dialogue. But, most importantly, they embody the connection between life and music, between hope, happiness, and harmony: they make music alive.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2022