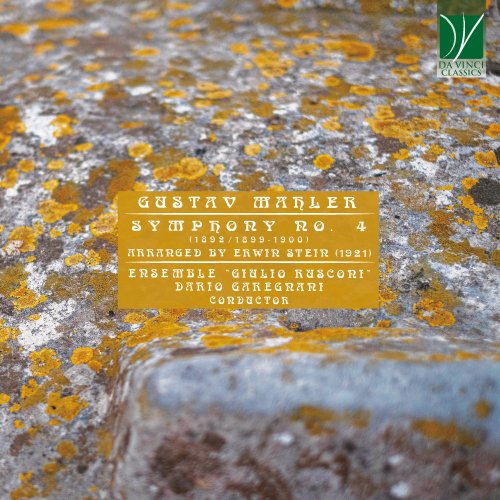

Artist:

Ensemble "Giulio Rusconi", Dario Garegnani, Beatrice Binda

Title:

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 (1892/1899-1900) - Arranged by Erwin Stein (1921)

Year Of Release:

2022

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 54:37

Total Size: 249 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:01. Symphony No. 4: I. Bedächtig, Nicht eilen, recht gemächlich (Arranged by Erwin Stein)

02. Symphony No. 4: II. Im gemächlicher Bewegung (Arranged by Erwin Stein)

03. Symphony No. 4: III. Ruhevoll (Arranged by Erwin Stein)

04. Symphony No. 4: IV. Sehr behaglich "Das himmlische Leben" (Arranged by Erwin Stein)

Written between 1899 and 1901, Gustav Mahler’s Fourth Symphony in G major is, among the great composer’s works, one of those whose character is more pronouncedly that of chamber music. Within the large symphonic output of the Bohemian composer, the Fourth Symphony closes a compositional period when (in the words of Bruno Walter, the first great performer and exegete of Mahler’s oeuvre) the expressed and unexpressed word complete each other. The first four Symphonies, ironically dubbed “my own Tetralogy” by Mahler himself (who thus acknowledged his debt toward Wagner), constitute in fact a self-enclosed component of his output, and – in spite of their obvious differences – have many traits in common. Going backwards from those years, the Third and the Second Symphony had already included the (more or less abundant) use of vocal materials and ensembles. In the First Symphony, the matter of a Lied having been turned instrumental had flowed. In parallel with this, in the Fourth Mahler chose to make use of a work dating from 1892, Das himmlische Leben, excerpted from the Lied collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn. This was a collection of poetry, published in the early nineteenth century and edited, among others, by Clemens Brentano, which – as happened with other Romantic publications, such as the Ossian poems – claimed to be the recovery of medieval poems, but was in most cases a contemporaneous forgery. In spite of this, it represented a source of inspiration for the Romantic idealisation of the Middle Ages and of their worldview. Mahler was enthralled by the collection when he found it at his friends’ place, and set several of its Lieder as a song collection (with piano and with orchestra accompaniment), under the title of Des Knaben Wunderhorn. One of the Lieder (not included in this song collection by Mahler) was planned to be included as a movement of the Third Symphony, which originally was intended to comprise seven movements, globally titled – in a typically Mahlerian fashion – as “what a child tells me”. As Mahler’s work on the Third progressed, he decided to excise the Lied – even though he had already cited fragments from it in the other movements of the Symphony, in order to impart it the cyclical form which he cherished so much. The atmosphere of enchantment, beauty and mystery found in the depiction of the “heavenly life” as seen by a child became, instead, the inspiration for the entire Fourth Symphony. That Lied, Das himmlische Leben, written for a soprano voice, has been in fact frequently performed by a child treble, in order to render in an even more efficacious fashion its suggestive sound, and the recounting of a vision where both the material world and visionary abstraction live together. Originally, also the Fourth should have had a different shape, comprising six movements, three of which should have been vocal and three instrumental.

The vision of heaven conjured by the last movement (in which Paradise is represented as a festive banquet) should have been counterbalanced, and partly explained, by that of “earthly life” found in another Lied. “Earthly life”, indeed, does not mean living for the senses, in this case – quite the contrary: the Lied’s lyrics portray the cruel death by starvation of a child whom the adults fail to rescue due to their daily business. This dark perspective also explains the eerie atmosphere of the second movement, a slow Scherzo in which the orchestra’s solo violin is the protagonist. The instrument has to be tuned one tone higher, thus acquiring a shrill and screeching sound, meant to represent the haunting serenade through which Death, playing the violin, shepherds the innocent children to their grave. In spite of this sombre style, which anticipates the Kindertotenlieder and thus represents a constant (and perhaps an idée fixe) in Mahler’s worldview, the slow movement is as pure and serene as a uniformly blue sky, as Mahler himself qualified it. It prepares and paves the way for the last movement, where the song resounds, depicting the beauty and bounty of heaven as a joyful and merry agape where saints and children happily mix together, eating plentifully, making music, and watching the dances of the blessed. The suggestion of a communication with the almost abstract world of childhood is very often found in the world of Mahler’s Lieder. It is it that determines a kind of a chronological and stylistic boundary within his oeuvre. The theoretical, conceptual, and certainly practical issue of a (more or less needed) “programme” is central for the understanding of his compositional technique. From his very beginnings, Mahler had sought a precarious balance between the need to lead the listener through his interior journey, and the need to “clean” his work of all kinds of labels (and therefore of texts). As previously said, the Fourth represents a boundary line, prior to reaching another series of symphonic works where both voice and text have no more space or use. There is a continuing game of intimacy, of allusions, of quotes, of counterpoints, and of echoes. As a consequence, this fascinating work charmed, just two decades after its premiere, even the great Arnold Schoenberg. The composer, who is considered as the father of dodecaphony, proposed to a restricted circle of pupils, colleagues and friends of his, the work of transcription and arrangement of this masterpiece (originally written for large symphonic orchestra and voice) for a smaller ensemble. The transcription’s destination was one of the “private performances” which were held, for many years, precisely at Schoenberg’s place, with the composer himself performing. The gatherings came under the name of Society for Private Musical Performances, and had, in spite of their homely setting, a very serious imprint. The Fourth Symphony, in particular, came into the hands of, and had been assigned to, Erwin Stein, a pupil and friend of the host. Stein collaborated closely with Schoenberg in the organisation of the “Private Musical Performances”, and had also written the first article for the “Neue Formprinzipien” (New Formal Principles), where the basic tenets of the twelve-tone technique were discussed and laid down. After working in Vienna as a composer and teacher, Stein would end up in London, where he was forced to emigrate in 1938 due to the Nazi persecution of the Jews, and became a champion of Britten, Schoenberg and Mahler’s music working as an editor at Boosey and Hawkes. He had been personally acquainted with Mahler and had participated in the Amsterdam Mahler Festival in 1920, remaining in correspondence with the Bohemian composer. Stein would also write an obituary for Schoenberg, stating that the composer “and his art had been a source of inspiration to us; we keenly anticipated any new work he would produce, curious to learn the ways of his imagination”. The result of Stein’s transcription, a hundred years after its composition, is surprising. Not only the ensemble (which is in the end much smaller than that of the original) betrays nothing with respect to the complete score, respecting every single note, every single harmony, and every single, precious instrumental pattern; rather, it ends up exalting the contrapuntal texture of this work. Indeed, the Symphony’s original large ensemble (though relatively small if one considers the size of one of the earlier and later symphonies) at times seems to damage the intelligibility of polyphony.

Stein’s work projects over this work a particular patina, a subtle, very personal veil. It represents a Vienna which had much changed in those twenty years. It is as if we could read a great classic, a great masterpiece (and in those few years so many musical works came into the hands of Schoenberg’s club…) through a decolouring lens. It is capable of covering the elegance of Mahler’s Vienna with the decadent sensibility of the same world, twenty years later. The Lied Das himmlische Leben, constituting the Symphony’s fourth movement, is the quintessence of Lied-writing, with its classical, elegant, neat melodic line. It is the vocal transfiguration of a vision of the heavenly life, through images of a rural daily life. The result is little less than sixty minutes long, with an extreme technical difficulty and a great musical intensity. Even today, the time spent with Mahler’s Fourt Symphony can lead both performers and audience not just into Mahler’s vision, but into the essential heart of his compositional power. It is as if we could, in turn, participate in the essential kernel of an immortal work. It is brought back to its essentiality, which is capable, every time, of leaving us breathless. When facing the essentiality of this minimal instrumentation, we are left with the feeling of the rendition’s extreme completeness. There is an essentiality without a reduction, a lossless transcription, where the message is not impoverished, but rather there is a purification, elevation, and distillation. Just has had been prescribed for the voice’s character, it is a rereading ohne Parodie, with great seriousness, respect, and engagement. This is a cornerstone of the entire symphonic repertoire, which, as if by miracle, and without losing any of its notes, becomes something else. There is nostalgia, awareness of the past, distance, loss. In a word: the twentieth century.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2022