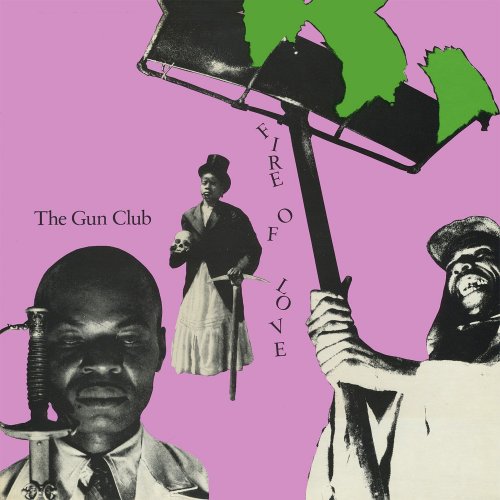

The Gun Club - Fire of Love (Remastered 2020) (2020) Hi-Res

Artist: The Gun Club

Title: Fire of Love (Remastered 2020)

Year Of Release: 1981 / 2020

Label: Blixa Sounds

Genre: New Wave, Post-Punk, Garage Rock, Psychobilly, Blues Rock

Quality: 320 / FLAC (tracks) / FLAC (tracks) 24bit-44.1kHz

Total Time: 53:50

Total Size: 125 / 362 / 634 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Fire of Love (Remastered 2020)

Year Of Release: 1981 / 2020

Label: Blixa Sounds

Genre: New Wave, Post-Punk, Garage Rock, Psychobilly, Blues Rock

Quality: 320 / FLAC (tracks) / FLAC (tracks) 24bit-44.1kHz

Total Time: 53:50

Total Size: 125 / 362 / 634 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Sex Beat (Remastered 2020) (2:48)

02. Preaching the Blues (Remastered 2020) (4:01)

03. Promise Me (Remastered 2020) (2:38)

04. She’s Like Heroin to Me (Remastered 2020) (2:35)

05. For the Love of Ivy (Remastered 2020) (5:37)

06. Fire Spirit (Remastered 2020) (2:50)

07. Ghost on the Highway (Remastered 2020) (2:47)

08. Jack on Fire (Remastered 2020) (4:46)

09. Black Train (Remastered 2020) (2:13)

10. Cool Drink of Water (Remastered 2020) (6:20)

11. Goodbye Johnny (Remastered 2020) (3:47)

12. Bad Indian (Alternate Version) (Remastered 2020) (2:26)

13. Cool Drink of Water (Alternate Version) (Remastered 2020) (1:01)

14. Fire of Love (Alternate Version) (Remastered 2020) (1:50)

15. For the Love of Ivy (Alternate Version) (Remastered 2020) (5:33)

16. Ghost on the Highway (Alternate Version) (Remastered 2020) (2:47)

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today we revisit the incendiary, hell-bent debut from the Los Angeles punk band who used blues and rockabilly to paint a depraved portrait of a young artist in their purest state.

London punk turned pub rock into protest music; New York punk reframed noise as art. But compared to those more celebrated first-wave scenes, L.A. punk was both more traditionalist and transgressive, the sound of faded glamour degenerating into fuck-it-all nihilism. Home to both the celebrity-industrial complex and the second-largest homeless population in the country, Los Angeles has always been the city that represents the folly of the American Dream, a place where happiness is manufactured for the big screen and hope goes to die under the sun. And by the late 1970s, the tension between the fantasy of L.A. and its reality had reached a breaking point. As local punk patriarch John Doe of X once put it, L.A. back then “looked like something between Roger Corman and Tennesee Williams. One of the Os in [the] ‘Hollywood’ [sign] had fallen down. It was in total decay.”

The natural response to living in a desperate, dangerous town is to make desperate, dangerous music. While the Germs and Black Flag pulverized punk into hardcore, bands like X and the Blasters approached punk as a rescue mission, by forging a spiritual connection with the primal hoots and howls of ’50s-jukebox oldies. And then there was the Gun Club, whose ringleader, Jeffrey Lee Pierce, looked so far back into the past—to the emotional bloodletting of Depression-era blues—that he wound up seeing the future, opening up a trail that indie rockers and roots artists would travel for decades to come. But what makes the Gun Club’s 1981 debut, Fire of Love, so timeless isn’t just that it set the stage for outlaw eccentrics like the Pixies, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, and the White Stripes (while providing Nick Cave with his post-Birthday Party roadmap into the swamp). It’s an eternally captivating portrait of a young artist in their purest state—hungry, drunk on attitude, and committed to their vision to the point of seeming supernaturally possessed.

Pierce wasn’t the most obvious candidate for punk sainthood; at heart, he was more of a studious fanboy than a natural frontman. Born to an American father and Mexican mother, Pierce was raised in the working-class east L.A. community of El Monte before relocating to the Valley suburb of Granada Hills—“the Los Angeles that nobody ever bothers with,” as he called it. A voracious reader and record collector, Pierce became the teenage president of the Blondie fan club and worked the counter at Bomp Records, before making vagabond journeys to New York, New Orleans, and Jamaica. (His time in Jamaica dovetailed with a reggae obsession that saw him review records for L.A. scene bible Slash under the pen name Ranking Jeffrey Lea.) His own musical pursuits were equally impulsive: Upon dissolving his short-lived art-pop outfit Red Lights, Pierce formed a new band with fellow Chicano Brian Tristan after the two attended a Pere Ubu show at the Whiskey A Go-Go in 1979, initially using it as a vehicle to indulge their mutual love of soul and reggae.

That band was initially known as the Creeping Ritual, before Black Flag/Circle Jerks singer Keith Morris suggested a switch to the Gun Club. (In return, Pierce gifted Morris the lyrics to the title track for the Jerks’ 1980 debut, Group Sex.) But the name wasn’t the only thing that had changed. Through friendships with local record-collecting zine-maker Phast Phreddie Patterson and ex-Canned Heat singer Bob Hite, Pierce immersed himself in the blues, embracing it as both the original outsider’s music and as a strategic device to distinguish the Gun Club from his punk peers more clearly beholden to a ’60s-garage/Stooges lineage. “Anything before the ’60s can be fascinating, because so much time has passed,” he explained in a 1982 interview. “The ’60s just completely demolished everybody’s minds, and so people aren’t really aware of most of the musical forms before then … there’s more fresh and wild ideas going on there.”

Today, the concept of punks playing the blues may not seem so radical in a world where Jack White oversees a commercial empire and the Black Keys play arenas, but in 1980, no self-respecting aesthete would touch the stuff. After all, classic rock’s fealty to American blues—and all the machismo and 17-minute guitar solos it engendered—was a big part of the reason punk happened. But in his essay that accompanies Blixa Sound’s 40th-anniversary reissue of the album, drummer Terry Graham observes: “My half-drunk opinion was that Jeff loved and hated the blues, but his love/hate was the alchemy that transformed an age-old hindrance into a brand new advantage.”

Key to this transformation was Tristan’s slide guitar, which yields some of Fire of Love’s bedrock riffs. But the guitarist didn’t stick around to see it through. With the Gun Club still playing to mostly empty rooms in L.A., Tristan accepted an offer to replace Bryan Gregory in the far more popular Cramps (where he became forever known as Kid Congo Powers). The loss of his co-founding partner presented an early indication that the Gun Club wasn’t going to be some tight-knit gang, but a fluid entity that would regularly reinvent itself in response to Pierce’s ever-changing whims. (As Graham says in the 2006 documentary Ghost on the Highway: “[Pierce] was just simply going to stuff his head with knowledge, express that knowledge somehow, and it just didn’t make any difference who was behind him, who was with him doing it, or who was in front of him watching him do it.”)

Tristan’s defection to the Cramps also provided a useful yardstick for measuring what made the Gun Club so singular. Pierce didn’t fit into any established punk archetypes: He wasn’t your typical leather-clad tough guy, he wasn’t a goth, he wasn’t some greasy coiffed, rockabilly revivalist. Though fond of performance-art provocation—like an early gig where he dressed up in Colonel Sanders garb and beat on a Bible with a chain—he didn’t have the lithe physique or cool stage-stalking presence of a Lux Interior. With his bottle-blonde hair and surplus-store assemblage of army coats, jackboots, and sabertooth necklaces, he looked less like Debbie Harry’s little brother and more like the drummer for an aspiring hair-metal band.

But Pierce had a big mouth and possessed a disarming, mercurial singing voice that was feral and fearful in equal measure. Most crucially, unlike the Cramps, Pierce channeled rock’n’roll’s primordial ooze free of camp or kitsch. Gun Club songs didn’t exist inside some imaginary B-movie, but in the darkest chapters of American history and the most depraved recesses of the male id. And that sense of psychological torment defines Fire of Love as much as any slide-guitar riff or desert-storming backbeat.

By 1981, Pierce had locked in a lineup featuring Graham and bassist Rob Ritter (both of L.A. punk mainstays the Bags) and rockabilly enthusiast Ward Dotson on guitar. Culled from two quickie sessions done on the cheap, Fire of Love is a masterpiece of thriftiness and expediency. On their smash-and-grab reclamation of Robert Johnson’s “Preachin’ Blues”—renamed “Preaching the Blues”—the band isn’t so much upgrading the genre for the hardcore era as trying to bash through their repertoire before getting the boot from the studio. The rhythm section pounds the ground so furiously, they practically start to glide across it.

Fire of Love’s crackling live-in-the-studio energy (complete with Pierce’s audible bandleader direction) and natural reverb create a late-night atmosphere every bit as thick and intoxicating as the most ostentatious rock opera. And for all of the album’s raw, cinéma-vérité qualities, Pierce crafts his lyrics with a painterly touch, constructing a netherworld that channels westerns and old-time religion one moment, porno mags and dive-bar bathroom graffiti the next.

Pierce doesn’t so much sing the blues as mainline them, pushing his nervous energy into more outrageous—and, at times, troubling—displays of bravado. He delivers his signature rave-ups “Sex Beat” and “She’s Like Heroin to Me” like someone who’d pick a fight with the biggest guy in the room even though he knows he’ll get his ass kicked. And while “Jack on Fire” is a comparatively laid-back walking blues, its breathless lyrical procession of Southern Gothic imagery, voodoo mysticism, and snuff-film depravity goads Pierce into one of his most gripping, magnetic performances.

Then, of course, there’s the searing centerpiece “For the Love of Ivy.” The song not only showcases the Gun Club at peak blues-punk fury, but also displays a command of silence, space, and tension that evokes L.A.’s original prophets of doom, the Doors. Part hat-tip to the 1968 Sidney Poitier film For Love of Ivy, part love letter to the Cramps’ untouchably cool guitarist, “For the Love of Ivy” teeters on the precipice where sexual desire descends into murderous bloodlust, with Pierce unleashing some of the most unsettling screams this side of Suicide’s “Frankie Teardrop.” If it were the only song Pierce had ever released, “For the Love of Ivy” would still make him a legend. After all these years, each lyric-capping cry of “Hell!” still feels like a fresh jump-scare.

In plumbing the depths of evil, “For the Love of Ivy” also betrays Pierce’s tendency to lose himself in his crackpot characters—which, in this case, means uttering a particularly ugly line about his deranged protagonist “hunting for n*****s down in the dark.” (A similarly disturbing phrase turns up in the cowpunk odyssey “Black Train.”) Saying the N-word was something of a taboo sport among otherwise progressive old-school punks, whether they were using it as an expression of outcast solidarity or holding a mirror up to society’s ugliest impulses or shoving it back in the racists’ faces. Still, its appearance in “Ivy” was and remains especially jarring coming from an artist who devoted so much of his life to studying and celebrating Black music and who, as a biracial man himself, was no stranger to feeling like a second-class citizen in his own country. For Pierce, the process of mining America’s musical past also meant dredging up the historical social tensions that shaped it. Committing to the bit meant occasionally employing the vile vernacular of the rednecks he caricatured. (That Fire of Love came from an era when punks like Pierce felt like they had poetic license to use such language is ultimately the only thing that dates the record.)

Of course, Pierce didn’t need to use racial slurs to alienate people. The same maniacal zeal that attracted musicians into his orbit was also the very thing that drove them away. Though Fire of Love made the Gun Club a hot property in post-punk circles—particularly in New York and Europe—its lineup didn’t even survive the making of the band’s second record, Miami. Ritter walked out of the sessions and Dotson followed suit after they wrapped. (Dotson was so traumatized by his experience working with Pierce, he would later admit that, years after his departure, he still harbored a deep-seated desire to whack him with a golf club.) From there, the Gun Club’s music would turn more artful and cinematic—even acquiring a dream-pop shimmer on 1987’s Robin Guthrie-produced Mother Juno—but their internal dysfunction only intensified, as Pierce’s control-freak tendencies and worsening substance abuse problems would see him cycle through a procession of players before he died of a brain hemorrhage in 1996 at 37.

While Pierce never stopped expanding his vision for the Gun Club over the course of his career, it was never more focused than on Fire of Love. And nowhere is his maniacal self-belief more deeply felt than on “Fire Spirit,” a snarling rocker that functions as his own personal—and eerily prophetic—theme song. “I can see clearly/From my diamond eyes,” he declares off the top, “I’m going to the mountain with the fire spirit/No one will accept all of me/So the fire… will stop.” Personal demons may have extinguished Pierce’s flame far too soon, but each time a needle drops on Fire of Love, it burns anew.

London punk turned pub rock into protest music; New York punk reframed noise as art. But compared to those more celebrated first-wave scenes, L.A. punk was both more traditionalist and transgressive, the sound of faded glamour degenerating into fuck-it-all nihilism. Home to both the celebrity-industrial complex and the second-largest homeless population in the country, Los Angeles has always been the city that represents the folly of the American Dream, a place where happiness is manufactured for the big screen and hope goes to die under the sun. And by the late 1970s, the tension between the fantasy of L.A. and its reality had reached a breaking point. As local punk patriarch John Doe of X once put it, L.A. back then “looked like something between Roger Corman and Tennesee Williams. One of the Os in [the] ‘Hollywood’ [sign] had fallen down. It was in total decay.”

The natural response to living in a desperate, dangerous town is to make desperate, dangerous music. While the Germs and Black Flag pulverized punk into hardcore, bands like X and the Blasters approached punk as a rescue mission, by forging a spiritual connection with the primal hoots and howls of ’50s-jukebox oldies. And then there was the Gun Club, whose ringleader, Jeffrey Lee Pierce, looked so far back into the past—to the emotional bloodletting of Depression-era blues—that he wound up seeing the future, opening up a trail that indie rockers and roots artists would travel for decades to come. But what makes the Gun Club’s 1981 debut, Fire of Love, so timeless isn’t just that it set the stage for outlaw eccentrics like the Pixies, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, and the White Stripes (while providing Nick Cave with his post-Birthday Party roadmap into the swamp). It’s an eternally captivating portrait of a young artist in their purest state—hungry, drunk on attitude, and committed to their vision to the point of seeming supernaturally possessed.

Pierce wasn’t the most obvious candidate for punk sainthood; at heart, he was more of a studious fanboy than a natural frontman. Born to an American father and Mexican mother, Pierce was raised in the working-class east L.A. community of El Monte before relocating to the Valley suburb of Granada Hills—“the Los Angeles that nobody ever bothers with,” as he called it. A voracious reader and record collector, Pierce became the teenage president of the Blondie fan club and worked the counter at Bomp Records, before making vagabond journeys to New York, New Orleans, and Jamaica. (His time in Jamaica dovetailed with a reggae obsession that saw him review records for L.A. scene bible Slash under the pen name Ranking Jeffrey Lea.) His own musical pursuits were equally impulsive: Upon dissolving his short-lived art-pop outfit Red Lights, Pierce formed a new band with fellow Chicano Brian Tristan after the two attended a Pere Ubu show at the Whiskey A Go-Go in 1979, initially using it as a vehicle to indulge their mutual love of soul and reggae.

That band was initially known as the Creeping Ritual, before Black Flag/Circle Jerks singer Keith Morris suggested a switch to the Gun Club. (In return, Pierce gifted Morris the lyrics to the title track for the Jerks’ 1980 debut, Group Sex.) But the name wasn’t the only thing that had changed. Through friendships with local record-collecting zine-maker Phast Phreddie Patterson and ex-Canned Heat singer Bob Hite, Pierce immersed himself in the blues, embracing it as both the original outsider’s music and as a strategic device to distinguish the Gun Club from his punk peers more clearly beholden to a ’60s-garage/Stooges lineage. “Anything before the ’60s can be fascinating, because so much time has passed,” he explained in a 1982 interview. “The ’60s just completely demolished everybody’s minds, and so people aren’t really aware of most of the musical forms before then … there’s more fresh and wild ideas going on there.”

Today, the concept of punks playing the blues may not seem so radical in a world where Jack White oversees a commercial empire and the Black Keys play arenas, but in 1980, no self-respecting aesthete would touch the stuff. After all, classic rock’s fealty to American blues—and all the machismo and 17-minute guitar solos it engendered—was a big part of the reason punk happened. But in his essay that accompanies Blixa Sound’s 40th-anniversary reissue of the album, drummer Terry Graham observes: “My half-drunk opinion was that Jeff loved and hated the blues, but his love/hate was the alchemy that transformed an age-old hindrance into a brand new advantage.”

Key to this transformation was Tristan’s slide guitar, which yields some of Fire of Love’s bedrock riffs. But the guitarist didn’t stick around to see it through. With the Gun Club still playing to mostly empty rooms in L.A., Tristan accepted an offer to replace Bryan Gregory in the far more popular Cramps (where he became forever known as Kid Congo Powers). The loss of his co-founding partner presented an early indication that the Gun Club wasn’t going to be some tight-knit gang, but a fluid entity that would regularly reinvent itself in response to Pierce’s ever-changing whims. (As Graham says in the 2006 documentary Ghost on the Highway: “[Pierce] was just simply going to stuff his head with knowledge, express that knowledge somehow, and it just didn’t make any difference who was behind him, who was with him doing it, or who was in front of him watching him do it.”)

Tristan’s defection to the Cramps also provided a useful yardstick for measuring what made the Gun Club so singular. Pierce didn’t fit into any established punk archetypes: He wasn’t your typical leather-clad tough guy, he wasn’t a goth, he wasn’t some greasy coiffed, rockabilly revivalist. Though fond of performance-art provocation—like an early gig where he dressed up in Colonel Sanders garb and beat on a Bible with a chain—he didn’t have the lithe physique or cool stage-stalking presence of a Lux Interior. With his bottle-blonde hair and surplus-store assemblage of army coats, jackboots, and sabertooth necklaces, he looked less like Debbie Harry’s little brother and more like the drummer for an aspiring hair-metal band.

But Pierce had a big mouth and possessed a disarming, mercurial singing voice that was feral and fearful in equal measure. Most crucially, unlike the Cramps, Pierce channeled rock’n’roll’s primordial ooze free of camp or kitsch. Gun Club songs didn’t exist inside some imaginary B-movie, but in the darkest chapters of American history and the most depraved recesses of the male id. And that sense of psychological torment defines Fire of Love as much as any slide-guitar riff or desert-storming backbeat.

By 1981, Pierce had locked in a lineup featuring Graham and bassist Rob Ritter (both of L.A. punk mainstays the Bags) and rockabilly enthusiast Ward Dotson on guitar. Culled from two quickie sessions done on the cheap, Fire of Love is a masterpiece of thriftiness and expediency. On their smash-and-grab reclamation of Robert Johnson’s “Preachin’ Blues”—renamed “Preaching the Blues”—the band isn’t so much upgrading the genre for the hardcore era as trying to bash through their repertoire before getting the boot from the studio. The rhythm section pounds the ground so furiously, they practically start to glide across it.

Fire of Love’s crackling live-in-the-studio energy (complete with Pierce’s audible bandleader direction) and natural reverb create a late-night atmosphere every bit as thick and intoxicating as the most ostentatious rock opera. And for all of the album’s raw, cinéma-vérité qualities, Pierce crafts his lyrics with a painterly touch, constructing a netherworld that channels westerns and old-time religion one moment, porno mags and dive-bar bathroom graffiti the next.

Pierce doesn’t so much sing the blues as mainline them, pushing his nervous energy into more outrageous—and, at times, troubling—displays of bravado. He delivers his signature rave-ups “Sex Beat” and “She’s Like Heroin to Me” like someone who’d pick a fight with the biggest guy in the room even though he knows he’ll get his ass kicked. And while “Jack on Fire” is a comparatively laid-back walking blues, its breathless lyrical procession of Southern Gothic imagery, voodoo mysticism, and snuff-film depravity goads Pierce into one of his most gripping, magnetic performances.

Then, of course, there’s the searing centerpiece “For the Love of Ivy.” The song not only showcases the Gun Club at peak blues-punk fury, but also displays a command of silence, space, and tension that evokes L.A.’s original prophets of doom, the Doors. Part hat-tip to the 1968 Sidney Poitier film For Love of Ivy, part love letter to the Cramps’ untouchably cool guitarist, “For the Love of Ivy” teeters on the precipice where sexual desire descends into murderous bloodlust, with Pierce unleashing some of the most unsettling screams this side of Suicide’s “Frankie Teardrop.” If it were the only song Pierce had ever released, “For the Love of Ivy” would still make him a legend. After all these years, each lyric-capping cry of “Hell!” still feels like a fresh jump-scare.

In plumbing the depths of evil, “For the Love of Ivy” also betrays Pierce’s tendency to lose himself in his crackpot characters—which, in this case, means uttering a particularly ugly line about his deranged protagonist “hunting for n*****s down in the dark.” (A similarly disturbing phrase turns up in the cowpunk odyssey “Black Train.”) Saying the N-word was something of a taboo sport among otherwise progressive old-school punks, whether they were using it as an expression of outcast solidarity or holding a mirror up to society’s ugliest impulses or shoving it back in the racists’ faces. Still, its appearance in “Ivy” was and remains especially jarring coming from an artist who devoted so much of his life to studying and celebrating Black music and who, as a biracial man himself, was no stranger to feeling like a second-class citizen in his own country. For Pierce, the process of mining America’s musical past also meant dredging up the historical social tensions that shaped it. Committing to the bit meant occasionally employing the vile vernacular of the rednecks he caricatured. (That Fire of Love came from an era when punks like Pierce felt like they had poetic license to use such language is ultimately the only thing that dates the record.)

Of course, Pierce didn’t need to use racial slurs to alienate people. The same maniacal zeal that attracted musicians into his orbit was also the very thing that drove them away. Though Fire of Love made the Gun Club a hot property in post-punk circles—particularly in New York and Europe—its lineup didn’t even survive the making of the band’s second record, Miami. Ritter walked out of the sessions and Dotson followed suit after they wrapped. (Dotson was so traumatized by his experience working with Pierce, he would later admit that, years after his departure, he still harbored a deep-seated desire to whack him with a golf club.) From there, the Gun Club’s music would turn more artful and cinematic—even acquiring a dream-pop shimmer on 1987’s Robin Guthrie-produced Mother Juno—but their internal dysfunction only intensified, as Pierce’s control-freak tendencies and worsening substance abuse problems would see him cycle through a procession of players before he died of a brain hemorrhage in 1996 at 37.

While Pierce never stopped expanding his vision for the Gun Club over the course of his career, it was never more focused than on Fire of Love. And nowhere is his maniacal self-belief more deeply felt than on “Fire Spirit,” a snarling rocker that functions as his own personal—and eerily prophetic—theme song. “I can see clearly/From my diamond eyes,” he declares off the top, “I’m going to the mountain with the fire spirit/No one will accept all of me/So the fire… will stop.” Personal demons may have extinguished Pierce’s flame far too soon, but each time a needle drops on Fire of Love, it burns anew.

![Tony Davis - Jessamine (2025) [Hi-Res] Tony Davis - Jessamine (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-11/1763089800_b542apxa83rlc_600.jpg)

![Charles Mingus - Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (1964) [2025 SACD] Charles Mingus - Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (1964) [2025 SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-11/1763011975_ucgu-9080.jpg)