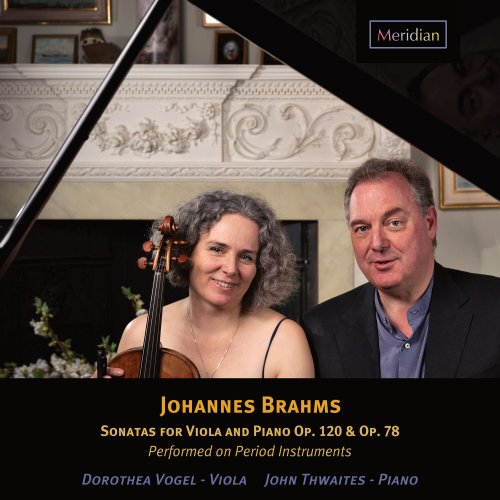

Dorothea Vogel, John Thwaites - Brahms: Sonatas for Viola and Piano Op. 120 & Op. 7 (2023) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Dorothea Vogel, John Thwaites

Title: Brahms: Sonatas for Viola and Piano Op. 120 & Op. 7

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Meridian Records

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 192.0kHz

Total Time: 01:08:13

Total Size: 278 mb / 2.54 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Brahms: Sonatas for Viola and Piano Op. 120 & Op. 7

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Meridian Records

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 192.0kHz

Total Time: 01:08:13

Total Size: 278 mb / 2.54 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 2: I. Allegro amabile

02. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 2: II. Allegro appassionato

03. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 2: III. Andante con moto-Allegro non troppo

04. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 1: I. Allegro appassionato

05. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 1: II. Andante, un poco Adagio

06. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 1: III. Allegretto grazioso

07. Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 120, No. 1: IV. Vivace

08. Violin Sonata G Major, Op. 78: I. Vivace ma non troppo (Arr. for Viola and Piano by Riebl/Vogel)

09. Violin Sonata G Major, Op. 78: II. Adagio (Arr. for Viola and Piano by Riebl/Vogel)

10. Violin Sonata G Major, Op. 78: III. Allegro molto moderato (Arr. for Viola and Piano by Riebl/Vogel)

In his book After the Golden Age Kenneth Hamilton takes a swipe at half-baked approaches to Historically Informed Performance Practice: "Some modern players of nineteenth-century pianos seem to feel uncomfortable with certain performance practices associated with the era. It is surprising how many award themselves a gold star for using historical instruments on recordings (sometimes chronologically bizarre ones) but steadfastly ignore the improvisation, unmarked arpeggiation of chords, and tempo flexibility that was such an important feature of much romantic performance practice." A similar swipe at string players might award only muted approbation for the use of gut strings if divorced from a varied use of vibrato and bow vibrato coupled to an enthusiastic embracing of vocal portamenti.

Dorothea Vogel and John Thwaites adopt a radically revisionist tone in these recordings, believing that both piano and string playing in the closing decades of the nineteenth century differed significantly from today's norms. They are indebted to the work of Professor Emeritus Clive Brown and the work that he and his colleagues have done for the Bärenreiter Brahms edition.

Dorothea Vogel: "I've always enjoyed the sound of older pianos. For me it's a sound that string players can relate to. Importantly these pianos give an acoustic space in which we can create a variety of tone colours without being forced to concentrate exclusively on projection. Piano parts don't sound thick, there aren't any balance problems, and the viola line is free to sing. In approaching these recordings I knew that I wouldn't want to be using continuous vibrato but that portamento (sliding the finger along the string) would become a bigger part of my vocal approach. Music happens between the notes, that is in the connection between notes. Making a portamento slide can link notes expressively and I have been happy to use much more portamento than I normally would, inspired by old recordings from the years just after Brahms's death. I have wanted to use slides where the music demands it, not simply where it feels most comfortable, and I've taken the same approach to a varied use of vibrato, and a willingness to sometimes let the pure tone of the gut speak simply (as Joachim seems to be doing in his recordings)."

John Thwaites: "I'm very fond of the extra overtones generated by this 1872 straight-strung Bösendorfer. The strings are under less tension so produce a more colourful sound. Each register has its own character, and this piano has a wonderfully guttural tenor and bass. It has a real brilliance in forte but in una corda the leather strip that covers the felt hammers lends a gentleness of extraordinary beauty. The "looseness" in the physical being of the instrument and (relative to the modern piano) the thinness and transparency of the sounds seem to naturally invite more rubato and rhythmic flexibility. I've found this personally agreeable since romantic freedom has been part of my musical makeup, for good or ill, since teenage years. Agogically inflecting "hairpins" (graphically notated mini crescendi followed by diminuendi) in the score, that is making hairpins expressive through rubato as well as volume, often by stretching and lingering in the middle of the hairpin, is now an accepted part of Brahms HIP interpretation. In this recording I've wanted to go further than ever before. Thalberg tells us, in his 1853 preface to L'Art du chant appliqué au piano that the normal way to play any piano chord is Presque Plaqué, that is almost together, that is, not together! And we know that nineteenth century pianists freely arpeggiated chords and often played the left hand before the right. Further, we can hear this in the early twentieth century recordings and piano rolls by the greatest pianists and composer-pianists. Throughout my life these recordings have been venerated as showcasing the most wonderful piano playing, truly representative of the Golden Age. Clearly the primary factor is that in those days only the very greatest of artists made recordings; all these men and women are extraordinary. But it does also raise a question as to whether the pianistic style in which they were raised contributes to this abundant musical creativity, and therefore whether we lesser mortals of the current time might purposefully allow ourselves some of these pianistic traits."

![Matt Choboter - And Then There Were The Sounds Of Birds (2026) [Hi-Res] Matt Choboter - And Then There Were The Sounds Of Birds (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771562657_qb70awhgfhge8_600.jpg)

![Tom Oren - Dark Lights (2026) [Hi-Res] Tom Oren - Dark Lights (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771427884_tdqtmzk78zgcb_600.jpg)