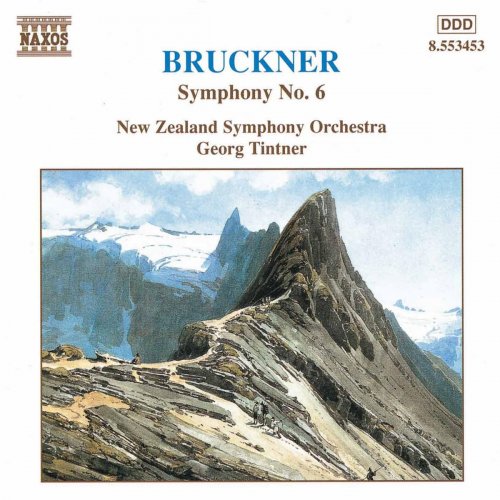

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Georg Tintner - Bruckner: Symphony No. 6, WAB 106 (1997)

Artist: New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Georg Tintner

Title: Bruckner: Symphony No. 6, WAB 106

Year Of Release: 1997

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:59:45

Total Size: 240 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Bruckner: Symphony No. 6, WAB 106

Year Of Release: 1997

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:59:45

Total Size: 240 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Symphony No. 6 in A Major, WAB 106: I. Maestoso

02. Symphony No. 6 in A Major, WAB 106: II. Adagio. Sehr feierlich

03. Symphony No. 6 in A Major, WAB 106: III. Scherzo. Nicht schnell - Trio: Langsam

04. Symphony No. 6 in A Major, WAB 106: IV. Finale. Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell

A mediaeval artisan might easily have kept a daily record of how many different prayers he prayed and how often he repeated them. For a composer of the nineteenth century, with its belief in unstoppable progress and human supremacy, to behave in this fashion is certainly unique. But Anton Bruckner, though accepting the harmonic and orchestral achievements of the Romantic period, did just that; he did not really belong to his time. Even less did he fit in with the Viennese environment into which he was transplanted for the last 27 years of his life. The elegant and rather superficial society he encountered there must have thought the naive, badly dressed fellow with the "wrong" accent a rather pathetic oddity.

Bruckner had indeed come from a very different background. The little village in Upper Austria, Ansfelden, where his father was a schoolmaster, was not far away from the great and beautiful monastery of St. Florian. The young Bruckner followed in the footsteps of his father for a short time; but St. Florian possessed one of Europe's finest organs, and young Anton, whose talent for music was discovered early, became an organist. The experience of hearing and playing this magnificent instrument became central to his whole life. He spent many hours there, practicing and improvising, and eventually his playing was so exceptional that he made successful tours of France and England as an organ virtuoso. He had lessons in theory and composition, and started composing fairly early in life, but he felt the need for more instruction in counterpoint and became for several years a most diligent pupil of the famous Simon Sechter, visiting him every fortnight in Vienna. Many years earlier and shortly before his death, Schubert had also wanted to study counterpoint with Sechter, but of course he was wrong; most of his life work was already done, and works such as his early Mass in A flat showed him in no need of such lessons.

Sechter forbade Bruckner to compose a single note in order to concentrate entirely on his innumerable exercises, and here Bruckner, who had in the meantime advanced to the post of organist at Linz Cathedral, showed one unfortunate trait of his character, perhaps acquired as an altar-boy: utter submission to those he considered his superiors. He obeyed. But when he had finished his instruction with Sechter and took lessons with the conductor of the local opera, Otto Kitzler, who introduced him to the magic world of Wagner, music poured out of him. Now forty,

Bruckner composed his first masterpiece, the wonderful Mass in D Minor, followed by two other great Masses, and Symphony No.1. His reputation reached Vienna and he was appointed to succeed Sechter as Professor of Music Theory.

Bruckner had ample reason to regret his move from Linz to Vienna. He, the fanatical admirer of Wagner, was innocently dragged into the rather silly conflict between the followers of Brahms and those of his beloved Wagner. So he made many enemies, most cruel of whom was the critic Eduard Hanslick, whom Wagner caricatured as Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger. But though adversaries did him harm, his friends and admirers hurt his works much more. All his young students were gifted Wagnerians and they thought Bruckner's music needed to sound more like Wagner, and that it needed other "ministrations" such as large cuts as well. They considered their beloved Master to be a "genius without talent."

Many of those misguided admirers, such as Artur Nikisch and Franz Schalk, became famous conductors and they set about making these enormous scores acceptable to the public - and it must be said that the master, who was desperately anxious to be performed, often agreed and sometimes even became an accomplice to their mutilations, but he also left his original scores to the National Library with the comment "for later times." His own insecurity made him constantly revise his works, especially Symphonies Nos. 1-4. As a result, we are confronted in many cases by several versions of the same work. Sometimes the later versions are a definite improvement, as with the Fourth Symphony; and sometimes, in my opinion, the first version is superior, as with the Second and Third Symphonies.

One who deals with eternal things is in no hurry, and therefore performers and listeners must also allow plenty of time. Whereas Mahler, who died three years before World War I began, was the prophet of insecurity, "Angst" and the horrors we live in, the deeply religious Bruckner sings of consolation and spiritual ecstasy (Verzuckung) - but not exclusively. In some of the Eighth and most of the Ninth Symphonies, he expresses agony, perhaps doubt.

Bruckner called the Sixth Symphony his boldest. It certainly is one of his most beautiful, yet it is not as frequently performed as most of its sisters. Perhaps the reason is that the Finale in contrast to the perfect first three movements is not absolutely satisfactory. In spite of this, Bruckner who sometimes created as many as three versions of a symphony, wrote only one version of this one. The arrangement by his pupil Hynais, though its changes are less drastic than those perpetrated elsewhere by the Schalk brothers and Ferdinand Lo ewe, is obsolete, despite the fact that the master may have tolerated it.

Instead of the usual tremolo, the work begins with a complex rhythmical figure in the violins. Bruckner's predilection for two notes against three, either behind each other or on top of one another, is particularly important in this symphony and in the Adagio of the Fifth Symphony. Celli and basses sing to this rhythmical figure an (even for Bruckner) outstandingly beautiful tune. It is in the Phrygian mode, the same as in the wonderful second movement of Brahms's Fourth Symphony. After an energetic continuation the theme recurs in full splendour. Gradually a transition leads us to the lovely and complex second tune, four notes against six, which is played considerably slower and which-in contrast to the main tune-consists almost exclusively of steps. After a rather heroic theme the exposition ends quietly. The development is in the slower tempo of the second melody. After a new, beautiful melody we hear a great increase in intensity and speed and the main tune returns in a remote key but in the original faster tempo. By an extremely simple device reinforced by the timpani we are back in the main key for the recapitulation. The lovely coda unfolds still in the slower tempo of the second tune, leading to the faster triumphant ending which slows down considerably at the very end.

The serene first melody of the second movement is accompanied in slow steps by the lower strings. An unexpected lament in the oboe disturbs the serenity. Gradually we are led to one of Bruckner's greatest tunes, led by the celli and first violins. Eventually the tempo gets even slower, leading into a kind of funeral march. The recapitulation starts in the original tempo; later the main theme reappears, richly embroidered. The second melody sings this time in the main key of the movement. The coda is very serene and remains for a long time in the principal key, an unusual procedure for Bruckner.

The frightening Scherzo is along with that of his Ninth Symphony, his most original. It is slower than most and as with that of his Eighth Symphony, has to be beaten in three beats, in contrast to most scherzos that are conducted in one. Over a constant pulse in the basses, triplet quavers in the middle strings and a phrase of repeated notes in the woodwind, the short motif in the violins sound like cries for help. Even the two powerful endings in major keys fail to supply relief from the oppressive atmosphere.

In the more positive Trio, plucked strings softly playa dotted rhythm and are answered by loud calls from three horns. A startling quotation of the main theme of the first movement of his Fifth Symphony proves to me that the tempo of the Trio must not be too slow. The Trio's quiet ending is followed once more by the expressionistic Scherzo.

The Finale starts interestingly enough. A rather austere tune in the violins is seconded by the second clarinet. After its repeat in the subdominant it is rudely interrupted by the trumpets and horns, who assert the main key in a very loud and rhythmical fashion. The whole orchestra then plays a new brass tune full of semitones and brings forth-another rather heroic melody. After all these monumental utterances a charming, dance-like melody beguiles us. Then over a soft major chord in the horns, the oboes and clarinets introduce a new tune as from far away (it is a distant relation to the oboe lament in the second movement, but here is in major).Bruckner must have been in love with this melody, but the more often it appears, the richer and louder it is orchestrated and (it seems to me) the more banal It becomes. Now the first tune is played considerably slower by the celli accompanied by the trombones, the second violins also in the slower tempo play the main tune, richly embroidered, in a remote key. The brass tunes are also slower here until the whole orchestra asserts the main key once more in the faster, original tempo. After a rather virtuosic passage in the violins (a rarity in Bruckner's works) the charming country tune reappears in the home key. The final loud and rhythmical assertion of the main key appears rather unexpectedly and perhaps not quite convincingly. Not even the quotation of the main tune of the first movement in the trombones can obliterate a feeling of slight dissatisfaction. So in the Sixth Symphony we have three perfect movements and one that is somewhat problematical - at least to me.