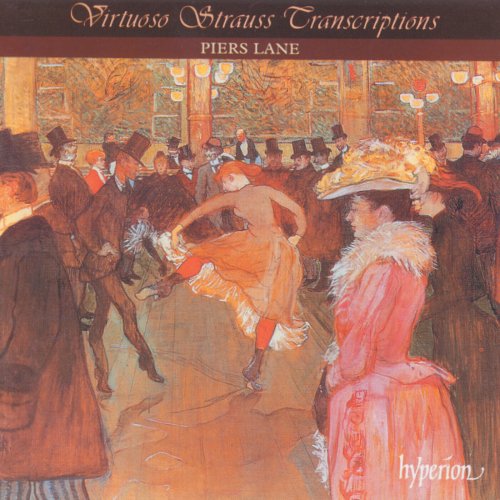

Piers Lane - Virtuoso Johann Strauss Transcriptions for Piano (1995)

Artist: Piers Lane

Title: Virtuoso Johann Strauss Transcriptions for Piano

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:13:34

Total Size: 236 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Virtuoso Johann Strauss Transcriptions for Piano

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:13:34

Total Size: 236 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Schulz-Evler, J. Strauss II: Arabesques on "An der schönen blauen Donau" by J. Strauss II

02. J. Strauss II: Frühlingsstimmen, Op. 410 (Arr. Friedman)

03. J. Strauss II, Moriz Rosenthal: Carnaval de Vienne (Arr. Rosenthal)

04. Tausig, J. Strauss II: Nouvelles soirées de Vienne, Valses-caprices d'après J. Strauss II: I. Nachtfalter (After Op. 157)

05. Tausig, J. Strauss II: Nouvelles soirées de Vienne, Valses-caprices d'après J. Strauss II: II. Man lebt nur einmal (After Op. 167)

06. Tausig, J. Strauss II: Nouvelles soirées de Vienne, Valses-caprices d'après J. Strauss II: III. Wahlstimmen (After Op. 250)

07. Godowsky: Symphonische Metamorphosen Johann Strauss’scher Themen: II. Die Fledermaus

08. J. Strauss II, Moriz Rosenthal: Fantasy on Johann Strauss Themes (The Blue Danube, Die Fledermaus & Freut euch des Lebens)

The present recital offers eight Viennese bonbons in the most elegant and cultivated of pianistic wrappings. All are by great pianist-composers—as opposed to composer-pianists, another breed which included the broader creative reaches of Liszt, Busoni, Rachmaninov and Dohnányi. Both types, however, had but two aims in taking a piece of music and transforming its orchestral or vocal origins into a persuasive pianistic composition: to show off their particular keyboard skills and to provide their listeners with an ear-tickling frisson.

The genesis of the nineteenth-century virtuoso transcription is clear: from the fairly straightforward arrangements of themes from the latest operas and symphonies (the only way that people in outlying areas could get to hear new music) to the heavily personalized fantasies and ‘reminiscences’ of Liszt and Thalberg from the 1830s onwards. Here the transcriber moulded the material to suit his own whim or to make his own comment on the music. The tradition extended to the first few decades of the twentieth century and major composers like Ravel, Stravinsky and Prokofiev went to pains to make elaborate piano versions of some of their own work.

Probably no composer has been used more frequently for these pianistic firework displays than Johann Strauss II. He composed very little piano music himself, but what a wealth of piano literature he was indirectly responsible for! The lilting Viennese waltz and Strauss’s unforgettable melodies proved to be seductive forces which few of the pianistic lions of the day could resist. The best of these transcriptions make you forget the orchestral original, convincing you that the keyboard acrobatic high-wire act was born in the heart of the instrument. This is not surprising, for the finest were written by pianists who knew the piano inside out and exactly how to exploit it to their advantage. Of these, the most distinguished were Alfred Grünfeld (1852–1924), Eduard Schütt (1856–1933), Ernst von Dohnányi (1877–1960) and the five pianist-composers featured on this recording.

Strangely, the all-embracing Liszt made no arrangements of Strauss’s music but left it instead to his favourite pupil, the extravagantly gifted Carl Tausig (1841–1871), and the three earliest examples in this recital are by him. It is a scandal that so few pianists think to include Tausig in their repertoire these days. There was a time when his Pastorale and Capriccio (delicate touchings-up of two Scarlatti sonatas), the magnificently pianistic transfiguration of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, the grandiose version of Schubert’s Marche Militaire and Andantino and Variations (wonderfully recorded by Egon Petri), Schumann’s song Der Contrabandiste and the witty decoration of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance were regularly played by the great artists of pre-war days. Not any more. Yet these were epoch-making transcriptions for their time, extending the lyrical and dramatic potential of the piano. (Someday, someone will champion Tausig’s original works and show precisely what a talent was lost at the age of thirty.)

Two other Tausig transcriptions have clung to the fringe of today’s programmes. In the early 1860s he made arrangements of three waltzes by Johann Strauss II—Nachtfalter (‘Night Moth’, Op 157), Man lebt nur einmal (‘Man only lives once’, Op 167) and Wahlstimmen (‘Election votes’, Op 250). Collectively entitled Nouvelles Soirées de Vienne: Valses-Caprices d’après J. Strauss, they were dedicated to Liszt and, indeed, can be seen as a pendant to Liszt’s own Soirées de Vienne based on Schubert waltzes. Two further Valses-Caprices, dedicated to Hans von Bülow, were published posthumously (Nos 4 in E major and 5 in A major in an edition by Balakirev). All five have been recorded but it is only the first two that have ever been part of the virtuoso repertoire, Man lebt nur einmal graced by Rachmaninov’s alchemy in a 1927 recording that was outstanding even by his standards.

Perhaps the best-known piano transcription of a Strauss waltz is that by a pupil of Tausig, the Polish Andrei Schulz-Evler who was born in Radom in December 1852 and died in Warsaw in May 1905. Little is known of Schulz-Evler’s life after his studies at the Warsaw Conservatoire and with Tausig in Berlin. He became a professor at the Kharkov School of Music where he taught from 1888 until the year before his death. He composed fifty-two piano pieces and songs which have disappeared without trace with one notable exception—the fabulous Concert Arabesques on themes by Johann Strauss ‘By the Beautiful Blue Danube’. (Coincidentally, here is a second Strauss re-working that has provided the gramophone with one of its greatest treasures. The Schulz-Evler was a speciality of Josef Lhévinne and his 1928 RCA Victor disc is a spellbinding tour de force whose final page still leaves many a seasoned artist wondering how he did it.)

The Strauss-Tausig-Polish connection continues with a third pianist-composer. Moriz Rosenthal (1862–1946) not only studied with Karol Mikuli (a pupil of Chopin) but also, after his family moved to Vienna in 1875, with Rafael Joseffy, another pupil of Tausig who taught Rosenthal according to Tausig’s method. Rosenthal must have taken the Schulz-Evler version of The Blue Danube as a role model for his own fantastic elaborations—the Fantasie um Johann Strauss über die Walzer ‘An der schönen blauen Donau’, ‘Freut euch des Lebens’, ‘Fledermaus’, to give it its full title (but also identified in places somewhat confusingly as ‘Paraphrase on The Blue Danube’). Technically even more demanding than the Schulz-Evler (and some would say overloaded with elaborate pianistic configurations), Rosenthal develops the genre a stage further, amusing himself by combining the opening theme of The Blue Danube with another from Die Fledermaus in an ingenious contrapuntal display, though somewhat at the expense of the essential nature of the original. Rosenthal’s score is peppered with terrifying passages (including ascending semiquaver thirds in the left hand and—later—ascending semiquaver sixths in the right, both marked legatissimo quasi glissando, fearsome repeated notes and concluding indications to play triomfante and con somma bravura). In a second even more outrageous confection, Carnaval de Vienne (slyly subtitled ‘Humoresque’), he manages to surpass himself and briefly combine three themes simultaneously. First composed in May 1889, this was Rosenthal’s calling card—one which, though he never played it the same way twice, was much admired by Johann Strauss himself, who had become a close friend.

The Tausig-Strauss line is broken by the next and greatest of all piano transcribers, the Polish-born Leopold Godowsky (1870–1938). Virtually self-taught, he first burst upon the European musical scene after a spectacular debut in Berlin in 1900. Part of the reason behind the sensation he caused were his elaborations of a handful of Chopin’s Studies. Some he arranged for the left hand alone, some with a separate voice woven into the original fabric and, in a couple of items, he played two Studies simultaneously. Later in the programme he gave the ecstatic Berlin audience his ‘Contrapuntal paraphrase’ on that seminal Viennese piano waltz, Weber’s Invitation to the Dance. The polyphonic ingenuity Godowsky put on show went far beyond the flashy entertainments of Moriz Rosenthal, then at the height of his fame (and who, incidentally, was keen to pave the way for Godowsky’s European triumph).

Godowsky’s expertise in pianistic contrapuntal writing was put to good use in elaborate treatments of themes from three Johann Strauss operettas, Künstlerleben, Die Fledermaus and Wein, Weib und Gesang. (A fourth was written much later in 1928 for the left hand alone on the Schatz-Walzer themes from The Gypsy Baron; yet a fifth on The Blue Danube was completed but lost when Godowsky was unable to return to Vienna at the outbreak of the First World War—he never sought to recapture the contents of the manuscript.) He called these paraphrases ‘Symphonic Metamorphoses’, a solemn but accurate description, for they are symphonic in texture, and in the dense interplay of their harmonic and thematic ideas. ‘Johann Strauss waltzing with Johann Bach’, one writer called them; ‘these are probably the last word in terpsichorean counterpoint’...

![Chris Forsyth - Chris Forsyth Plays Love Devotion Surrender (2024) [Hi-Res] Chris Forsyth - Chris Forsyth Plays Love Devotion Surrender (2024) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770021495_cover.jpg)

![Calibro 35 - Exploration (Deluxe Edition) (2026) [Hi-Res] Calibro 35 - Exploration (Deluxe Edition) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770195253_prs31td9h1vkc_600.jpg)

![David Chevallier, Sebastien Boisseau, Christophe Lavergne - ReSet (2026) [Hi-Res] David Chevallier, Sebastien Boisseau, Christophe Lavergne - ReSet (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770298536_cover.jpg)