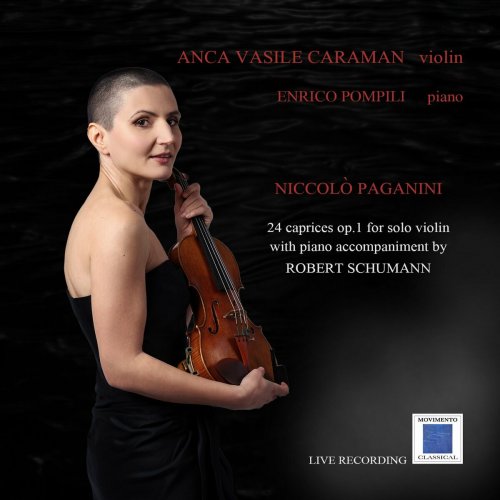

Anca Vasile Caraman - 24 Caprices, Op. 1 for Violin with Piano Accompaniment by Robert Schumann (2023) Hi-Res

Artist: Anca Vasile Caraman, Enrico Pompili

Title: 24 Caprices, Op. 1 for Violin with Piano Accompaniment by Robert Schumann

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Movimento Classical

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) / FLAC 24 Bit (44,1 KHz / tracks)

Total Time: 62:34 min

Total Size: 301 / 615 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: 24 Caprices, Op. 1 for Violin with Piano Accompaniment by Robert Schumann

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Movimento Classical

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) / FLAC 24 Bit (44,1 KHz / tracks)

Total Time: 62:34 min

Total Size: 301 / 615 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. 24 Caprice N. 1 in E Major: Andante

02. 24 Caprice N. 2 in B Minor: Moderato

03. 24 Caprice N. 3 in E Minor: Sostenuto, Presto, Sostenuto

04. 24 Caprice N. 4 in C Minor: Maestoso

05. 24 Caprice N. 5 in A Minor: Agitato

06. 24 Caprice N. 6 in G Minor: Lento

07. 24 Caprice N. 7 in A Minor: Posato

08. 24 Caprice N. 8 in E-Flat Major: Maestoso

09. 24 Caprice No. 9 in E Major: Allegretto

10. Caprice N. 10 in G Minor: Vivace

11. 24 Caprice N. 11 in C Major: Andante, Presto, Andante

12. 24 Caprice N. 12 in A-Flat Major: Allegro

13. 24 Caprice N.13 in B-Flat Major: Allegro

14. 24 Caprice N.14 in E-Flat Major: Moderato

15. 24 Caprice N.15 in E Major: Postato

16. 24 Caprice N.16 in G Minor: Presto

17. 24 Caprice N. 17 in E-Flat Major: Sostenuto, Andante

18. 24 Caprice N.18 in C Major: Corrente, Allegro, Corrente

19. 24 Caprice N. 19 in E-Flat Major: Lento, Allegro assai

20. 24 Caprice N. 20 in D Major: Allegretto

21. 24 Caprice N. 21 in A Major: Amoroso, Presto

22. 24 . Caprice N. 22 in F Major: Marcato

23. 24 Caprice N. 23 in E-Flat Major: Posato

24. 24 Caprice N. 24 in A Minor: Tema con Variazioni: Quasi Presto

On 9 June 1817, Paganini signed a private contrae! with the publisher Ricordi in which he undertook not to publish with any other publisher, neither in Milan nor in Europe, the five works thai he had just given him and thai had already been duly paid lor, namely the 24 Caprices lor Solo Violin (op. 1), the Sonatas lor Violin and Guitar (op. 2 and 3) and the Guitar Quartets (op. 4 and 5). Nothing is known of the negotiations that preceded and accompanied this publication, nor of when the 24 Caprices were composed. Ricordi did noi publish them, together with the Sonatas and Quartets, until 1820, thus three years alter Paganini had given them to him, which suggests that perhaps something had not gone so well in the relationship between the publisher and the musician.

Niccolò Paganini's 24 Caprices op. 1 did not initially cause much of a stir in the tracie press; however, they were reprinted in Leipzig by Breitkopf & Hàrtel as early as 1823, thus rather close to the first ltalian edition, and, probably in 1825, by Richault in Paris. In fact, they only carne back into conversation when Paganini, in the spring of 1828, began his long tour that look him triumphantly to all the major European musical capitals and transformed him !rom an exclusively locai phenomenon, limited to the ltalian sphere, into an international star; and in any case, the Caprices were lor a very long time the only Paganini virtuosic works available, because the Genoese violinist, very jealous of his cornpositions and afraid of being copied, was careful, as long as he lived, not to print his Concertos and his Themes with Variations. The appearance of the Genoese violinist on the European musical scene had, as it is well known, a decisive effect on the musical careers of two of the most important composers of the Romantic 19th century: Robert Schumann and Franz Liszt. lt was only alter hearing Paganini in a concert in Frankfurt am Main in 1830 that Robert Schumann decided once and tor all to become a musician and piano virtuoso, abandoning his law studies tor good. Two years alter Schumann, in 1832, Franz Liszt, too, alter attending a Parisian concert by Paganini, was seized by an irrepressible enthusiasm, and decided to completely renew his technique in the name of a transcendental virtuosity of Paganini's own making. For Liszt too, as tor Schumann, the discovery of Paganini was a catalysing event, capable of arousing new energie s, strengthening convictions, opening new horizons. Far both musicians, though so different in temperament and nature, Paganini was not simply a phenomenal violin virtuoso, even if he was the most ex1raordinary one ever to appear on the scene: he was, rather, the living embodiment of the most romantic of myths, that of 'going beyond' the very physical limits, in a yearning lor the infinite that brought with it a continuous 'challenge to the impossible'.

Liszt and Schumann therefore chose to immediately confront, albeit !rom different angles, the Genoese musician's rnost emblernatic work, the 24 Caprices op. 1. In 1831/2, alter unsuccessfully atternpting to complete a Fantasia lor piano and orchestra on Paganini themes, Schumann composed and published his 6 Etudes !rom Paganini's Caprices op. 3, followed some time later by his 6 Etudes op. 1O, which were printed in 1833, while in 1838 Liszt published the first version, of almost insurmountable difficulty, of his Études d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini.

In the journal of which he was editor, the "Neue Zeitschrilt tor Musik", Schumann devoted some space to his own op. 10 with a very enlightening self-review, published in 1836, which provides us with a useful key to the criteria thai had overseen the creation of the collection. «I believe that Paganini himself», Schumann writes, «esteems his own compositional talent more highly than his eminent virtuosic genius. Although, at least up to now, one may not entirely agree with him, one rnust nevertheless recognise thai in his compositions (and above all in the Caprices for violin, from which the Etudes we are discussing are taken and which, without exception, were conceived and compieteci with rare freshness and ease) there is such an abundance of diamonds that a richer setting, such as that required for the piano, can only strengthen, rather than weaken, these qualities».

Rather than attempting to transfer Paganini's extreme virtuosity onto the piano, as Liszt was to do, Schumann sought to recreate the poetic spirit of the Caprices on his instrument, thus assimilating them with his transcription to the nascent Romantic movement. He makes it, so to speak, his own work, to the extent that those unfamiliar with the originals, might well mistake these pages, or at least some of them, lor originai Schumann's works.

The piano adaptations of the Caprices were not the last of Schumann's contributions to Paganini's cause. In the spring of 1855, in the Endenich psychiatric clinic in Bonn, where he was hospitalised following the exacerbation of his mental problems and his attempted suicide on 27 February 1854, Schumann wrote what are perhaps his last musical pages with full meaning; namely the piano accompaniments to the Caprices by the Genoese musician. In his last years of activity, in fact, Schumann had manifested a growing interest in the violin, which materialised in 1851 in the composition of the two Sonatas lor violin and piano, op. 105 and op. 121, and two years later in the Fantasia op. 131 for violin and orchestra and, above all, in the beautiful and little-known Concerto in D minor for violin and orchestra. At the same time, Schumann sketched out the piano accompaniment tor Paganini's 24th Caprice. Alter being hospitalised in Endenich, in the spring of 1855, with his mind already severely disturbed, Schumann asked for the score of Paganini's Caprices to be brought to him in the mental home where he was staying, and there he composed the piano accompaniment for all 24 pieces; the score was found by his wife Clara in his papers only alter his death and was first published in 1930. This composition, which is the pendant to the similar accompaniment to Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, which Schumann had composed some time earlier, has a high symbolic value, even before its historical and musical value. lt is like a closing circle.

Paganini had marked the beginning of Schumann's career as a professional musician; and now, in this sad spring of 1855, it also marked the end of it. Let us once again recali the words Schumann had used nineteen years earlier in his sell-review ol op. 10: in the Caprices « there is such an abundance ol diamonds thai a richer setting, such as thai required tor lhe piano, can only strenglhen, ralher lhan weaken, lhese qualilies » . With his piano accompaniment, Schumann was now celebrating his persona! lribute to the musician he so admired, providing the Caprices with precisely thai richer «setting» thai the Romantic 19th century, with its horror vacui towards solo violin music, considered almost indispensable tor lheir concert performance. Schumann's example, kepl in the drawer by his wite Clara tor reasons only she could explain, did not remain isolateci: other lamous violinists, including Ferdinand David and Fritz Kreisler, lelt lhe need lo make adaptations ot the Caprices with piano accompanimenl in arder to perform them in their concerts; this type ot performance would indeed become the standard and would remain so until at least the second hall ol the 20th century, to the point that one would have to wait until 1950 lo lind the tirsi complete recording, by Ruggiero Ricci , ot all 24 pieces in their originai version lor solo violin, ergo wilhoul piano.

Niccolò Paganini's 24 Caprices op. 1 did not initially cause much of a stir in the tracie press; however, they were reprinted in Leipzig by Breitkopf & Hàrtel as early as 1823, thus rather close to the first ltalian edition, and, probably in 1825, by Richault in Paris. In fact, they only carne back into conversation when Paganini, in the spring of 1828, began his long tour that look him triumphantly to all the major European musical capitals and transformed him !rom an exclusively locai phenomenon, limited to the ltalian sphere, into an international star; and in any case, the Caprices were lor a very long time the only Paganini virtuosic works available, because the Genoese violinist, very jealous of his cornpositions and afraid of being copied, was careful, as long as he lived, not to print his Concertos and his Themes with Variations. The appearance of the Genoese violinist on the European musical scene had, as it is well known, a decisive effect on the musical careers of two of the most important composers of the Romantic 19th century: Robert Schumann and Franz Liszt. lt was only alter hearing Paganini in a concert in Frankfurt am Main in 1830 that Robert Schumann decided once and tor all to become a musician and piano virtuoso, abandoning his law studies tor good. Two years alter Schumann, in 1832, Franz Liszt, too, alter attending a Parisian concert by Paganini, was seized by an irrepressible enthusiasm, and decided to completely renew his technique in the name of a transcendental virtuosity of Paganini's own making. For Liszt too, as tor Schumann, the discovery of Paganini was a catalysing event, capable of arousing new energie s, strengthening convictions, opening new horizons. Far both musicians, though so different in temperament and nature, Paganini was not simply a phenomenal violin virtuoso, even if he was the most ex1raordinary one ever to appear on the scene: he was, rather, the living embodiment of the most romantic of myths, that of 'going beyond' the very physical limits, in a yearning lor the infinite that brought with it a continuous 'challenge to the impossible'.

Liszt and Schumann therefore chose to immediately confront, albeit !rom different angles, the Genoese musician's rnost emblernatic work, the 24 Caprices op. 1. In 1831/2, alter unsuccessfully atternpting to complete a Fantasia lor piano and orchestra on Paganini themes, Schumann composed and published his 6 Etudes !rom Paganini's Caprices op. 3, followed some time later by his 6 Etudes op. 1O, which were printed in 1833, while in 1838 Liszt published the first version, of almost insurmountable difficulty, of his Études d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini.

In the journal of which he was editor, the "Neue Zeitschrilt tor Musik", Schumann devoted some space to his own op. 10 with a very enlightening self-review, published in 1836, which provides us with a useful key to the criteria thai had overseen the creation of the collection. «I believe that Paganini himself», Schumann writes, «esteems his own compositional talent more highly than his eminent virtuosic genius. Although, at least up to now, one may not entirely agree with him, one rnust nevertheless recognise thai in his compositions (and above all in the Caprices for violin, from which the Etudes we are discussing are taken and which, without exception, were conceived and compieteci with rare freshness and ease) there is such an abundance of diamonds that a richer setting, such as that required for the piano, can only strengthen, rather than weaken, these qualities».

Rather than attempting to transfer Paganini's extreme virtuosity onto the piano, as Liszt was to do, Schumann sought to recreate the poetic spirit of the Caprices on his instrument, thus assimilating them with his transcription to the nascent Romantic movement. He makes it, so to speak, his own work, to the extent that those unfamiliar with the originals, might well mistake these pages, or at least some of them, lor originai Schumann's works.

The piano adaptations of the Caprices were not the last of Schumann's contributions to Paganini's cause. In the spring of 1855, in the Endenich psychiatric clinic in Bonn, where he was hospitalised following the exacerbation of his mental problems and his attempted suicide on 27 February 1854, Schumann wrote what are perhaps his last musical pages with full meaning; namely the piano accompaniments to the Caprices by the Genoese musician. In his last years of activity, in fact, Schumann had manifested a growing interest in the violin, which materialised in 1851 in the composition of the two Sonatas lor violin and piano, op. 105 and op. 121, and two years later in the Fantasia op. 131 for violin and orchestra and, above all, in the beautiful and little-known Concerto in D minor for violin and orchestra. At the same time, Schumann sketched out the piano accompaniment tor Paganini's 24th Caprice. Alter being hospitalised in Endenich, in the spring of 1855, with his mind already severely disturbed, Schumann asked for the score of Paganini's Caprices to be brought to him in the mental home where he was staying, and there he composed the piano accompaniment for all 24 pieces; the score was found by his wife Clara in his papers only alter his death and was first published in 1930. This composition, which is the pendant to the similar accompaniment to Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, which Schumann had composed some time earlier, has a high symbolic value, even before its historical and musical value. lt is like a closing circle.

Paganini had marked the beginning of Schumann's career as a professional musician; and now, in this sad spring of 1855, it also marked the end of it. Let us once again recali the words Schumann had used nineteen years earlier in his sell-review ol op. 10: in the Caprices « there is such an abundance ol diamonds thai a richer setting, such as thai required tor lhe piano, can only strenglhen, ralher lhan weaken, lhese qualilies » . With his piano accompaniment, Schumann was now celebrating his persona! lribute to the musician he so admired, providing the Caprices with precisely thai richer «setting» thai the Romantic 19th century, with its horror vacui towards solo violin music, considered almost indispensable tor lheir concert performance. Schumann's example, kepl in the drawer by his wite Clara tor reasons only she could explain, did not remain isolateci: other lamous violinists, including Ferdinand David and Fritz Kreisler, lelt lhe need lo make adaptations ot the Caprices with piano accompanimenl in arder to perform them in their concerts; this type ot performance would indeed become the standard and would remain so until at least the second hall ol the 20th century, to the point that one would have to wait until 1950 lo lind the tirsi complete recording, by Ruggiero Ricci , ot all 24 pieces in their originai version lor solo violin, ergo wilhoul piano.

![Peter Appleyard Orchestra - Percussive Jazz (Remastered) (19602025) [Hi-Res] Peter Appleyard Orchestra - Percussive Jazz (Remastered) (19602025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770205711_papj500.jpg)