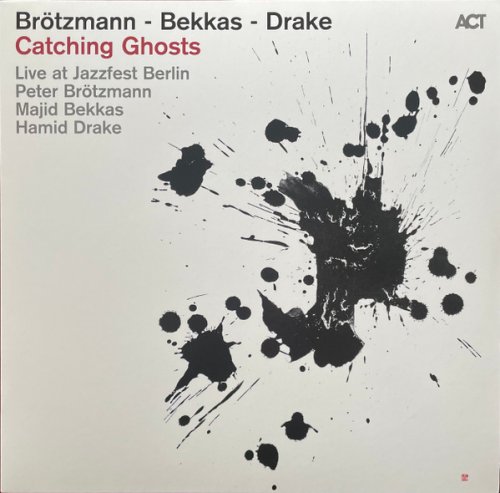

Brötzmann, Bekkas, Drake - Catching Ghosts (2023) LP

Artist: Brötzmann, Bekkas, Drake

Title: Catching Ghosts

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: ACT

Genre: Free Improvisation, Free Jazz

Quality: WavPack (tracks) 32/192

Total Time: 00:43:01

Total Size: 1.7 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Catching Ghosts

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: ACT

Genre: Free Improvisation, Free Jazz

Quality: WavPack (tracks) 32/192

Total Time: 00:43:01

Total Size: 1.7 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

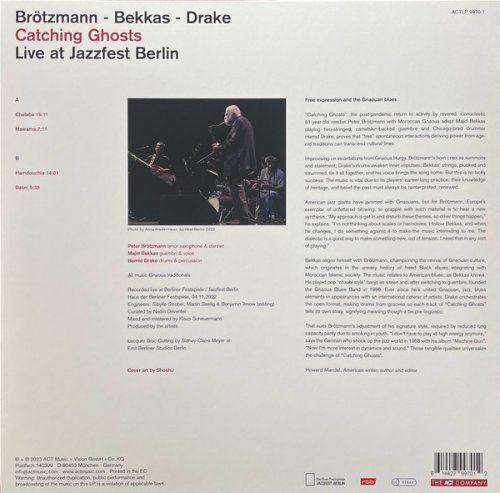

A1 Chalaba

A2 Mawama

B1 Hamdouchia

B2 Balini

Tenor Saxophone, Clarinet – Peter Brötzmann

Guimbri, Vocals – Majid Bekkas

Drums, Percussion – Hamid Drake

The 2022 Jazzfest Berlin performance by revered, iconoclastic reedist Peter Brötzmann, Moroccan Gnaoua adept Majid Bekkas playing the two-stringed, camelskin-backed guembri, and Chicago-bred drummer Hamid Drake, documented as Catching Ghosts, is historic.

It’s a return to performance by 81-year-old Brötzmann after pandemic years affected his health, and recalls his prior Gnaouan encounters, like The Catch of a Ghost (2019) with guembri master Maâlem Moukhtar Gania, and a 1996 meet with Maâlem Mahmoud Gania at Austria’s Music Unlimited Festival (Hamid there both times). It also is a triumph of musical universalism, made in the moment without even one rehearsal, proving that “free” spontaneous interactions can transcend cultural lines, still deriving power from age-old traditions.

Improvising on incantations from Gnaoua liturgy, Brötzmann, Bekkas and Drake convey “Chalaba,” “Mawama,” “Hamchia” and “Balini” so directly a listener without Arabic or Berber gets the messages. Hear saxophone, clarinet and tárogató cries as summons and statements; feel drums awaken inner impulses; sense strings, plucked and strummed, tying it all together, and a voice stressing the songs’ immediacy. But make no mistake: The music’s vitality and credibility are earned by its players’ decades of practice, career-long study of heritage, and embrace the paradox that the past must be reinterpreted, anew.

These Gnaouan chants have endured numerous modern Arabic adaptations, and jazz giants Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and Randy Weston have previously applied themselves to similar crossovers. But for Brötzmann, Europe’s exemplar of unfettered blowing, grapple with such material so deeply is to witness its greatest stretch yet, entering new territory.

“My approach to these themes is get in and disturb them, so other things happen,” Brötzmann explains. “I’m not thinking about scales or harmonies. I follow Bekkas, and when he changes, I do something against it to make the music interesting to me. I believe the dialectic is a good way to make something new, coming from tension. I need that in any sort of playing.

“From my youngest years I was interested in not doing what people said to do. I knew jazz history, and knew too I’m not a Black guy or American. I’m European, with my own background and arts education. I grew up after World War II, so it was natural to work against what was established. In the ‘60s we still fought leftovers from the Nazi times. Jazz has always been a peoples’ music, standing with the underdogs. With the rise again of nationalism -- which I did not think would happen in my lifetime -- we have to see that jazz stands for that again.”

Majid Bekkas aligns himself with Brötzmann, championing a revival of the Gnaoua culture. Its origins trace to the historic uneasy integration of freed Black slaves into Moroccan Islamic society; the music, even given religious connotations, resembles American blues. Although educated in classical guitar at Rabat’s Conservatory of Music and Dance, Bekkas at a teen played pop “chaabi style” banjo, but shifted to guembri as instructed by Ba Houmane, a street drummer in his hometown, Sale. Founding the Gnaoua Blue Band in 1990, Bekka has steadily incorporated blues, jazz, fusion and pop elements, appearing with Joachim Kuhn and Klaus Doldinger’s band Passport among others, since 1996 being co-artistic director of Rabat’s Jazz au Chellah Festival. Brötzmann says, “I’ve played with the strongest American bassists, and to me the Moroccans do something just as complicated, with similar drive. Bekkas and Hamid have a good rhythmic understanding, and when Bekkas adds his voice, all is fine.”

Drake’s contributions cannot be overstated. An equal in this trio and longtime partner with Brötzmann in such bands as the quartet Die Like a Dog and the Chicago Tentet, Hamid orchestrates the open format, making drama of metrical and timbral matters. Consequently, each track of Catching Ghosts tells its own story, clear to audiences anywhere attentive to gestures that signify though they are pre-linguistic.

That suits Peter Brötzmann just fine. In response to reduced lung capacity resulting in part from smoking as a youth, Brötzmann says he has adjusted his signature projection. “I don’t have to play all high energy anymore,” says the German who shook up the jazz world in 1968 with his roaring album Machine Gun. “Now I’m more interested in dynamics and sound.” Those are tangible, if nearly ephemeral qualities. Seductive tools for Catching Ghosts.

It’s a return to performance by 81-year-old Brötzmann after pandemic years affected his health, and recalls his prior Gnaouan encounters, like The Catch of a Ghost (2019) with guembri master Maâlem Moukhtar Gania, and a 1996 meet with Maâlem Mahmoud Gania at Austria’s Music Unlimited Festival (Hamid there both times). It also is a triumph of musical universalism, made in the moment without even one rehearsal, proving that “free” spontaneous interactions can transcend cultural lines, still deriving power from age-old traditions.

Improvising on incantations from Gnaoua liturgy, Brötzmann, Bekkas and Drake convey “Chalaba,” “Mawama,” “Hamchia” and “Balini” so directly a listener without Arabic or Berber gets the messages. Hear saxophone, clarinet and tárogató cries as summons and statements; feel drums awaken inner impulses; sense strings, plucked and strummed, tying it all together, and a voice stressing the songs’ immediacy. But make no mistake: The music’s vitality and credibility are earned by its players’ decades of practice, career-long study of heritage, and embrace the paradox that the past must be reinterpreted, anew.

These Gnaouan chants have endured numerous modern Arabic adaptations, and jazz giants Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and Randy Weston have previously applied themselves to similar crossovers. But for Brötzmann, Europe’s exemplar of unfettered blowing, grapple with such material so deeply is to witness its greatest stretch yet, entering new territory.

“My approach to these themes is get in and disturb them, so other things happen,” Brötzmann explains. “I’m not thinking about scales or harmonies. I follow Bekkas, and when he changes, I do something against it to make the music interesting to me. I believe the dialectic is a good way to make something new, coming from tension. I need that in any sort of playing.

“From my youngest years I was interested in not doing what people said to do. I knew jazz history, and knew too I’m not a Black guy or American. I’m European, with my own background and arts education. I grew up after World War II, so it was natural to work against what was established. In the ‘60s we still fought leftovers from the Nazi times. Jazz has always been a peoples’ music, standing with the underdogs. With the rise again of nationalism -- which I did not think would happen in my lifetime -- we have to see that jazz stands for that again.”

Majid Bekkas aligns himself with Brötzmann, championing a revival of the Gnaoua culture. Its origins trace to the historic uneasy integration of freed Black slaves into Moroccan Islamic society; the music, even given religious connotations, resembles American blues. Although educated in classical guitar at Rabat’s Conservatory of Music and Dance, Bekkas at a teen played pop “chaabi style” banjo, but shifted to guembri as instructed by Ba Houmane, a street drummer in his hometown, Sale. Founding the Gnaoua Blue Band in 1990, Bekka has steadily incorporated blues, jazz, fusion and pop elements, appearing with Joachim Kuhn and Klaus Doldinger’s band Passport among others, since 1996 being co-artistic director of Rabat’s Jazz au Chellah Festival. Brötzmann says, “I’ve played with the strongest American bassists, and to me the Moroccans do something just as complicated, with similar drive. Bekkas and Hamid have a good rhythmic understanding, and when Bekkas adds his voice, all is fine.”

Drake’s contributions cannot be overstated. An equal in this trio and longtime partner with Brötzmann in such bands as the quartet Die Like a Dog and the Chicago Tentet, Hamid orchestrates the open format, making drama of metrical and timbral matters. Consequently, each track of Catching Ghosts tells its own story, clear to audiences anywhere attentive to gestures that signify though they are pre-linguistic.

That suits Peter Brötzmann just fine. In response to reduced lung capacity resulting in part from smoking as a youth, Brötzmann says he has adjusted his signature projection. “I don’t have to play all high energy anymore,” says the German who shook up the jazz world in 1968 with his roaring album Machine Gun. “Now I’m more interested in dynamics and sound.” Those are tangible, if nearly ephemeral qualities. Seductive tools for Catching Ghosts.

![Petite Lucette - Incendier nos tristesses (2026) [Hi-Res] Petite Lucette - Incendier nos tristesses (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/11/9nx5amab4r25oheci73nsqybf.jpg)

![Marquis Hill - (Beautifulism) Sweet Surrender (2026) [Hi-Res] Marquis Hill - (Beautifulism) Sweet Surrender (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773243814_a2236776675_10.jpg)

![Svante Söderqvist The Rocket - Like in the Movies (2026) [Hi-Res] Svante Söderqvist The Rocket - Like in the Movies (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773245966_1.jpg)