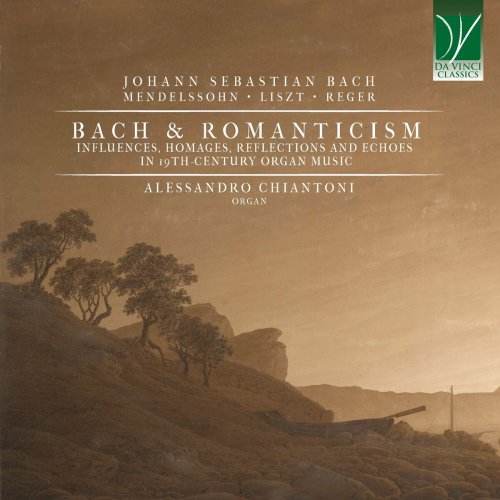

Alessandro Chiantoni - Bach, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Reger: Bach and Romanticism (Influences, Homages, Reflections and Echoes in 19th-Century Organ Music) (2024)

Artist: Alessandro Chiantoni

Title: Bach, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Reger: Bach and Romanticism (Influences, Homages, Reflections and Echoes in 19th-Century Organ Music)

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 82:56 min

Total Size: 372 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist|Title: Bach, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Reger: Bach and Romanticism (Influences, Homages, Reflections and Echoes in 19th-Century Organ Music)

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 82:56 min

Total Size: 372 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Dorische in D Minor, BWV 538: I. Toccata

02. Dorische in D Minor, BWV 538: II. Fugue

03. Sonata No. 6 in D Minor, Op. 65: I. Choral mit Variationen: Vater unser im Himmelreich

04. Sonata No. 6 in D Minor, Op. 65: II. Fuga: Sostenuto e legato

05. Sonata No. 6 in D Minor, Op. 65: III. Finale: Andante

06. Introduktion und Passacaglia in D Minor: I. Introduction

07. Introduktion und Passacaglia in D Minor: II. Passacaglia

08. Fantasie und Fuge über das Thema BACH, S.529: I. Fantasie (Syncretic Version by Jean Guillou)

09. Fantasie und Fuge über das Thema BACH, S.529: II. Fuge (Syncretic Version by Jean Guillou)

10. Sonata No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 65: I. Grave – Adagio

11. Sonata No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 65: II. Allegro maestoso e vivace

12. Sonata No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 65: III. Fuga, Allegro moderato

13. Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV 543: I. Prelude

14. Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV 543: II. Fugue

Some scholars who specialize in aesthetics (both of music and in general) argue that there is some affinity between two historical periods surrounding a third. Thus, for instance, there are shared aesthetic values between the Renaissance and Classicism, and between this and Neo Classicism. Between the former two, there is the Baroque era, and between the latter two is Romanticism. And, indeed, there are several points in common also between the Baroque and the Romantic era. This is of course a schematic and simplistic view, but also one not deprived of a grain of truth. In fact, the Romantics looked with respect and awe to the Baroque era; indeed, theirs was the first generation which, as a whole, took a historicist approach to music, and began to appreciate, study, and also perform the music of past eras.

Both the Romantics and their Baroque forerunners appreciated magnificence, greatness, sublimity; they liked to enchant and to be enchanted. They appreciated nature but also the supernatural; indeed, they saw nature as a gateway to the supernatural, in open polemics against Classical rationalism.

For Romantic musicians, Bach began to represent the summit of musical art. And, in particular, he was regarded by many as the embodiment of church music, and the model of how music and the sacred should interact. Under this viewpoint, Bach the organist had unrivalled fame. Indeed, even during his lifetime Bach was virtually never contested as an organist: even though his compositions did not suit everybody’s taste, and at times he was strongly attacked for some of his choices, his greatness as an organist was never under discussion.

He was greatly knowledgeable not only of organ playing, but also of organ building, and he was frequently called as an expert for the construction and testing of new organs, or repairs of older instruments. His skills at the organ involved a number of abilities. He was virtually unmatched as an improviser, both as concerns the freer and the most rigorous forms and genres. He had unsurpassable fantasy when the Baroque taste for the capricious, awesome, or even bizarre was stimulated. But he could also manage the intricacies of polyphony, frequently demonstrating his impressive ability in handling multiple melodic lines at one time, and respecting all the complex rule of contrapuntal writing – even without actually writing anything down!

Only later did he jot down and then finish and perfect in writing those pieces he had brilliantly invented as an improvisation, and this fresh, spontaneous nature is frequently observable even by the modern performer or listener.

This is the case with the two pairs of an improvisatory piece and a Fugue by Bach recorded in this Da Vinci Classics CD. In one case we have a Toccata: this word immediately refers to the Italian organ school, which had been particularly glorious in the early Baroque era, in particular with Frescobaldi (whom Bach greatly admired) but also with many others. Unfortunately, in the following centuries the Italian organ school would progressively vanish, up to an almost total disappearance in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth century, before being resurrected in the late Romantic era and in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

The appellation “Dorian” with which BWV 538 is commonly referred to is useful in order to distinguish this Toccata and Fugue in D minor from its homologue, “the” Toccata and Fugue by Bach – one of those pieces by the Leipzig composer which are known by the larger public, also thanks to its fortunate appearances on cinema screens.

The Dorian pair, however, is by no means inferior to its more famous sibling. “Dorian” was one of the Church modes (i.e. ways of organizing pitches: whereas tonal music has just the major and minor mode, in the Middle Ages and in the ecclesiastical tradition a mode could be built over any degree of the scale). And Bach did frequently employ it, particularly when harmonizing Lutheran chorales which often were written in this mode. However, in this particular case the appellative is a misnomer, because, if we wish to attribute a church mode to this pair, it would be more appropriately the Aeolian mode.

Both movements are among Bach’s finest for the organ, although they are very complex both to play and to listen to. The Toccata is characterized by its perpetuum mobile style, with an unending stream of semiquavers. Analyzing it, one is struck by the economy of means employed by Bach, who manages to derive every detail of this music from the opening motif, a superbly crafted theme. Another specificity of this piece is the careful indication of the alternation between Hauptwerk and Rückpositiv, in an effort at orchestration which is rarely found in Bach (except in his transcriptions from Italian concertos, where the alternation solo/tutti is found). Actually, though, Italianate elements are found almost everywhere in this Toccata, not only as concerns this dialogic approach, but also in terms of Italian violin performance, which is constantly evoked here. A reminiscence of the Toccata’s main motif is also found in the Fugue, in one of the countersubjects; thus, the pair manages to achieve noteworthy unity. Bach also makes abundant use of syncopations, which add to the rhythmic effectiveness of this piece; the concluding pedal part, just before the ending, crowns this spectacular pair with brilliant effectiveness.

In the case of BWV 543 (Digital Bonus Track), the Prelude and its Fugue were not conceived together; however, even though their times of composition are different, there is no contradiction or inhomogeneity among them, and the result is compact and efficacious. The Prelude dates back to Weimar, and the Fugue was written later; both, however, were constantly revised and reworked by Bach, until ca. 1725. Here too the influence of Italian music is discernible, and in particular references abound to Frescobaldi and to his Fiori musicali. Bach’s Prelude is similar to those written by the Italian maestro, inasmuch as both musicians seem to favour the unexpected and the capricious. The fantastic nature of these pieces, which look back to the genre of the Ricercare, from another point of view reduces the autonomy and importance of the Prelude, which ceases to exist, in a manner of speaking, if it is deprived of its fugue.

Here, the Fugue is the true protagonist of the pair, and the ease demonstrated by Bach in his handling of the musical material is once more impressive. The Fugue seems to showcase the possibilities of counterpoint, in a catalogue of solutions in terms of counterpoint but with a surprising fluency.

The complex genesis of this pair is mirrored in its sources and in its various versions. There are two clearly distinguished versions of the Prelude, whilst the Fugue is identical in them both. One aspect changed by Bach in the two versions of the Prelude is the rhythmical component, which changes in the direction of a greater solemnity and calm.

As is common knowledge among musicians and musicologists, the beginnings of the so-called “Bach Renaissance” (i.e. of the Romantics’ rediscovery of Bach and of his music) were due to Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, who, when still in his teens, inaugurated this movement with an epoch-making performance of the St Matthew Passion. Bach had been forgotten only by the large public, though; among professional musicians his figure was known and appreciated. Mendelssohn had been handed down the early Bach tradition by those in Bach’s immediate circle and their descendants.

For Mendelssohn, to study Bach implied to imitate his style and learn from it, and to play and conduct his music. And while Mendelssohn’s favourite instrument was the piano, he was also an excellent organist. Thus, his cycle of six Organ Sonatas op. 65 represents a homage to Bach, as well as one of the undisputed peaks of the Romantic organ output. Published in 1845, their composition predates their printing by a few years. In 1841, Mendelssohn had proposed to his publisher, Breitkopf, a cycle of 12 organ Etudes; in 1844, following a particularly successful concert tour in England, a British publisher commissioned a series of “voluntaries” which were eventually created by combining and adapting some earlier pieces. Mendelssohn selected or freshly composed some 24 short movements, constituting six four-movement Sonatas. The two Sonatas recorded here represent the diverse styles of the cycle: a more structured form, as in Sonata no. 2, and a freer one (No. 6). The Allegro maestoso of Sonata no. 2 had been written many years before, in Rome (1831), as a Nachspiel: in general this Sonata was created out of material written in 1831, 1839 and 1844; while the sixth Sonata comprises a series of Bach-inspired variations on the chorale Vater unser in Himmelreich, which, with their masterly construction and improvisational style, build up the longest movement in the whole cycle.

Variations are at the core also of Max Reger’s Introduction and Passacaglia, written in 1899 as an occasional piece to be included in the so-called Schönberger Orgelalbum, an album created after an idea by organist Ludwig Sauer for the purpose of funding a new organ at Schönberg im Taunus and comprising works also by Guilmant, Rheinberger and Widor. It is only seemingly a “minor work”: relatively short and not particularly complex to play, but extremely interesting and full of brilliant musical ideas.

An even more explicit homage to Bach is found in Franz Liszt’s Fantasie und Fuge über das Thema BACH, a work with a complex genesis. Initially written in 1855 for solo organ and titled “Prelude and Fugue”, it was later transcribed by the composer for solo piano; then, in 1870, he revised the organ work and re-transcribed it for piano. The “syncretic” version by Jean Guillou recorded here virtually incorporates everything Liszt inserted in the organ and piano versions. It displays the characteristic traits of Liszt’s keyboard output, in particular pronouncedly virtuoso technical demands. Bach’s family name provides the notes for the theme, whose huge chromatic potential is probed deeply by Liszt. Both Liszt and Mendelssohn, however, demonstrate their debt of gratitude to Bach mainly in their masterfully built final Fugues, where the maestro’s unsurpassed contrapuntal skills are clearly received with awed respect.

Chiara Bertoglio

Both the Romantics and their Baroque forerunners appreciated magnificence, greatness, sublimity; they liked to enchant and to be enchanted. They appreciated nature but also the supernatural; indeed, they saw nature as a gateway to the supernatural, in open polemics against Classical rationalism.

For Romantic musicians, Bach began to represent the summit of musical art. And, in particular, he was regarded by many as the embodiment of church music, and the model of how music and the sacred should interact. Under this viewpoint, Bach the organist had unrivalled fame. Indeed, even during his lifetime Bach was virtually never contested as an organist: even though his compositions did not suit everybody’s taste, and at times he was strongly attacked for some of his choices, his greatness as an organist was never under discussion.

He was greatly knowledgeable not only of organ playing, but also of organ building, and he was frequently called as an expert for the construction and testing of new organs, or repairs of older instruments. His skills at the organ involved a number of abilities. He was virtually unmatched as an improviser, both as concerns the freer and the most rigorous forms and genres. He had unsurpassable fantasy when the Baroque taste for the capricious, awesome, or even bizarre was stimulated. But he could also manage the intricacies of polyphony, frequently demonstrating his impressive ability in handling multiple melodic lines at one time, and respecting all the complex rule of contrapuntal writing – even without actually writing anything down!

Only later did he jot down and then finish and perfect in writing those pieces he had brilliantly invented as an improvisation, and this fresh, spontaneous nature is frequently observable even by the modern performer or listener.

This is the case with the two pairs of an improvisatory piece and a Fugue by Bach recorded in this Da Vinci Classics CD. In one case we have a Toccata: this word immediately refers to the Italian organ school, which had been particularly glorious in the early Baroque era, in particular with Frescobaldi (whom Bach greatly admired) but also with many others. Unfortunately, in the following centuries the Italian organ school would progressively vanish, up to an almost total disappearance in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth century, before being resurrected in the late Romantic era and in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

The appellation “Dorian” with which BWV 538 is commonly referred to is useful in order to distinguish this Toccata and Fugue in D minor from its homologue, “the” Toccata and Fugue by Bach – one of those pieces by the Leipzig composer which are known by the larger public, also thanks to its fortunate appearances on cinema screens.

The Dorian pair, however, is by no means inferior to its more famous sibling. “Dorian” was one of the Church modes (i.e. ways of organizing pitches: whereas tonal music has just the major and minor mode, in the Middle Ages and in the ecclesiastical tradition a mode could be built over any degree of the scale). And Bach did frequently employ it, particularly when harmonizing Lutheran chorales which often were written in this mode. However, in this particular case the appellative is a misnomer, because, if we wish to attribute a church mode to this pair, it would be more appropriately the Aeolian mode.

Both movements are among Bach’s finest for the organ, although they are very complex both to play and to listen to. The Toccata is characterized by its perpetuum mobile style, with an unending stream of semiquavers. Analyzing it, one is struck by the economy of means employed by Bach, who manages to derive every detail of this music from the opening motif, a superbly crafted theme. Another specificity of this piece is the careful indication of the alternation between Hauptwerk and Rückpositiv, in an effort at orchestration which is rarely found in Bach (except in his transcriptions from Italian concertos, where the alternation solo/tutti is found). Actually, though, Italianate elements are found almost everywhere in this Toccata, not only as concerns this dialogic approach, but also in terms of Italian violin performance, which is constantly evoked here. A reminiscence of the Toccata’s main motif is also found in the Fugue, in one of the countersubjects; thus, the pair manages to achieve noteworthy unity. Bach also makes abundant use of syncopations, which add to the rhythmic effectiveness of this piece; the concluding pedal part, just before the ending, crowns this spectacular pair with brilliant effectiveness.

In the case of BWV 543 (Digital Bonus Track), the Prelude and its Fugue were not conceived together; however, even though their times of composition are different, there is no contradiction or inhomogeneity among them, and the result is compact and efficacious. The Prelude dates back to Weimar, and the Fugue was written later; both, however, were constantly revised and reworked by Bach, until ca. 1725. Here too the influence of Italian music is discernible, and in particular references abound to Frescobaldi and to his Fiori musicali. Bach’s Prelude is similar to those written by the Italian maestro, inasmuch as both musicians seem to favour the unexpected and the capricious. The fantastic nature of these pieces, which look back to the genre of the Ricercare, from another point of view reduces the autonomy and importance of the Prelude, which ceases to exist, in a manner of speaking, if it is deprived of its fugue.

Here, the Fugue is the true protagonist of the pair, and the ease demonstrated by Bach in his handling of the musical material is once more impressive. The Fugue seems to showcase the possibilities of counterpoint, in a catalogue of solutions in terms of counterpoint but with a surprising fluency.

The complex genesis of this pair is mirrored in its sources and in its various versions. There are two clearly distinguished versions of the Prelude, whilst the Fugue is identical in them both. One aspect changed by Bach in the two versions of the Prelude is the rhythmical component, which changes in the direction of a greater solemnity and calm.

As is common knowledge among musicians and musicologists, the beginnings of the so-called “Bach Renaissance” (i.e. of the Romantics’ rediscovery of Bach and of his music) were due to Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, who, when still in his teens, inaugurated this movement with an epoch-making performance of the St Matthew Passion. Bach had been forgotten only by the large public, though; among professional musicians his figure was known and appreciated. Mendelssohn had been handed down the early Bach tradition by those in Bach’s immediate circle and their descendants.

For Mendelssohn, to study Bach implied to imitate his style and learn from it, and to play and conduct his music. And while Mendelssohn’s favourite instrument was the piano, he was also an excellent organist. Thus, his cycle of six Organ Sonatas op. 65 represents a homage to Bach, as well as one of the undisputed peaks of the Romantic organ output. Published in 1845, their composition predates their printing by a few years. In 1841, Mendelssohn had proposed to his publisher, Breitkopf, a cycle of 12 organ Etudes; in 1844, following a particularly successful concert tour in England, a British publisher commissioned a series of “voluntaries” which were eventually created by combining and adapting some earlier pieces. Mendelssohn selected or freshly composed some 24 short movements, constituting six four-movement Sonatas. The two Sonatas recorded here represent the diverse styles of the cycle: a more structured form, as in Sonata no. 2, and a freer one (No. 6). The Allegro maestoso of Sonata no. 2 had been written many years before, in Rome (1831), as a Nachspiel: in general this Sonata was created out of material written in 1831, 1839 and 1844; while the sixth Sonata comprises a series of Bach-inspired variations on the chorale Vater unser in Himmelreich, which, with their masterly construction and improvisational style, build up the longest movement in the whole cycle.

Variations are at the core also of Max Reger’s Introduction and Passacaglia, written in 1899 as an occasional piece to be included in the so-called Schönberger Orgelalbum, an album created after an idea by organist Ludwig Sauer for the purpose of funding a new organ at Schönberg im Taunus and comprising works also by Guilmant, Rheinberger and Widor. It is only seemingly a “minor work”: relatively short and not particularly complex to play, but extremely interesting and full of brilliant musical ideas.

An even more explicit homage to Bach is found in Franz Liszt’s Fantasie und Fuge über das Thema BACH, a work with a complex genesis. Initially written in 1855 for solo organ and titled “Prelude and Fugue”, it was later transcribed by the composer for solo piano; then, in 1870, he revised the organ work and re-transcribed it for piano. The “syncretic” version by Jean Guillou recorded here virtually incorporates everything Liszt inserted in the organ and piano versions. It displays the characteristic traits of Liszt’s keyboard output, in particular pronouncedly virtuoso technical demands. Bach’s family name provides the notes for the theme, whose huge chromatic potential is probed deeply by Liszt. Both Liszt and Mendelssohn, however, demonstrate their debt of gratitude to Bach mainly in their masterfully built final Fugues, where the maestro’s unsurpassed contrapuntal skills are clearly received with awed respect.

Chiara Bertoglio

![Amira Kheir - Black Diamonds (2025) [Hi-Res] Amira Kheir - Black Diamonds (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765640459_tf7wrmc9lqmqc_600.jpg)