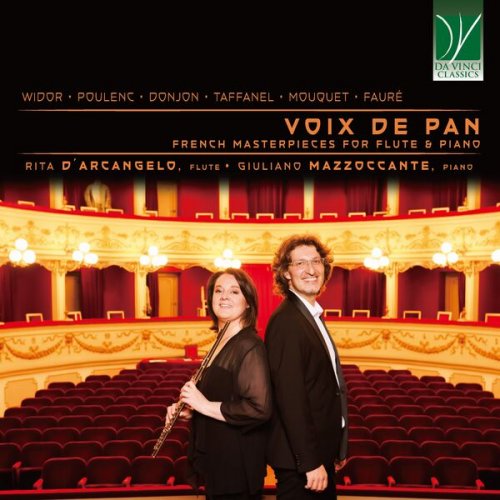

Rita D´Arcangelo, Giuliano Mazzoccante - Widor, Poulenc, Donjon, Taffanel, Mouquet, Fauré: Voix De Pan (French Masterpieces for Flute & Piano) (2024) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Da Vinci Classics

Title: Classical

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 00:59:58

Total Size: 242 / 957 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Classical

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 00:59:58

Total Size: 242 / 957 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Suite for flute and piano, Op. 34: I. Moderato

02. Suite for flute and piano, Op. 34: II. Scherzo

03. Suite for flute and piano, Op. 34: III. Romance

04. Suite for flute and piano, Op. 34: IV. Final

05. Flute Sonata, FP 164: I. Allegro malinconico

06. Flute Sonata, FP 164: II. Cantilena

07. Flute Sonata, FP 164: III. Presto giocoso

08. Elegie

09. Andante Pastoral et Scherzettino: I. Andante Pastoral

10. Andante Pastoral et Scherzettino: II. Scherzettino

11. La Flute de Pan, Sonate for flute and piano, Op. 15: I. Pan et les bergers

12. La Flute de Pan, Sonate for flute and piano, Op. 15: II. Pan et les oiseaux

13. La Flute de Pan, Sonate for flute and piano, Op. 15: III. Pan et les nymphes

14. Morceau de Concours: Adagio non troppo

![Rita D´Arcangelo, Giuliano Mazzoccante - Widor, Poulenc, Donjon, Taffanel, Mouquet, Fauré: Voix De Pan (French Masterpieces for Flute & Piano) (2024) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2024-01/1706220894_rita-darcangelo-giuliano-mazzoccante-widor-poulenc-donjon-taffanel-mouquet-2024-back.jpg)

Music is a universal language. It transcends linguistic and (most) cultural borders. Yet it is not nationless or without idiosyncrasies determined by place and local culture. There are, therefore, instruments which are more closely associated with a particular place than with another. This does not apply just to folk instruments (as the Scottish bagpipes, the Spanish guitar, or the Russian balalaika, to name but few) but also to instruments which are fully part of the “international” musical panorama and of the Classical Symphony Orchestra. Thus, the violin is by no means a “local” instrument; yet, there is a closeness between Hungarian/gipsy music and the violin which is lacking elsewhere. Similarly, the flute is as universal an instrument as there can be (it is probably the most common instrument in all epochs and cultures), but it has a privileged relationship with France.

This was because there was an excellent school of flute playing in France, particularly since the nineteenth century, and, consequently, plenty of superb performers. This, in turn, encouraged the production of new music for the flute by some of the greatest French (or French speaking) composers in the Romantic and modern era. Much was also owed to some charismatic figures, such as that of Paul Taffanel, a legendary performer and pedagogue, to whom countless technical innovations and musical ideas are credited, and whose exceptional standing encouraged other musicians to be involved in flute music. In fact, this is one aspect of the “French flute phenomenon”: whereas good flute composers are found throughout Europe and beyond its borders, many of them were first and foremost flute players themselves. In France, instead, some of the most important musicians of the national panorama were happy to dedicate themselves to flute music, as is demonstrated by this Da Vinci Classics album.

The first work featured here is by a composer whose lasting fame actually was associated with an instrument, but one rather different from the flute – i.e. the organ. Charles-Marie Widor, in fact, is practically synonymous with organ music, and very little of his output which does not include the organ is commonly known.

Widor’s Suite op. 34 was written, not by chance, for Paul Taffanel, and it is a characteristic work where Neoclassical and late-Romantic influences merge rather fluently (even though, in principle, Neoclassicism and Romanticism are in strong mutual contrast).

Widor’s father was an organist in turn, and he educated his child in both the organ and the piano. Charles-Marie quickly emerged as a virtuoso of both instruments, and impressed most favourably Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, the founder of the legendary organ-building company. Widor’s career included both performance (at the church of St. Sulpice in Paris) and teaching (he was a professor of organ and later of composition at the Conservatoire de Paris). The work recorded here is one of the very few of his non-organistic pieces which enjoyed durable success. Its composition can be dated at approximately 1877; it was premiered by Paul Taffanel at the Society of Wind Instrument Chamber Music in Paris (1884). The term Suite is rather a misnomer here, since the work resembles more closely to a Sonatina; its musical material is kept together through the use of a leading motif. Therefore, the piece acquires a noteworthy compactness and tightness.

It was published first by Hamelle, around 1885/6, and later reprinted by Heugel in 1897; the piece underwent some revisions, particularly in the Final’s ending, whose character acquired increased brilliance (possibly following Taffanel’s suggestions). This work is particularly cherished by flutists and listeners alike, thanks to the abundant palette of expressiveness and timbre it requires and display.

But if Widor’s Suite is a favourite of both musicians and audience, the same applies, and to an even higher degree, to Francis Poulenc’s Flute Sonata, which ranks among the most beloved and performed pieces in flute literature, and with good reason. It is absolutely adorable: very compact in size, with an amiable mood throughout, plenty of joy and good humour in spite of occasional melancholies, the right amount of virtuosity which is always functional to musical expressiveness… and a few memorable themes which stick in the listener’s mind even after just one hearing.

Poulenc was born a few years after the publication of Widor’s Suite, and was soon encouraged to study the piano; among his teachers was legendary Ricardo Viñès, who provided his student with excellent piano skills which are mirrored also in the piano part of this Sonata.

After some difficult years following the untimely death of his parents, Poulenc became a member of the Groupe des Six, which led the innovation of French Classical music in the twentieth century. The Sonata recorded here dates from his last years, and was composed in parallel with another of Poulenc’s masterpieces, Dialogues des Carmélites – a profound opera which is almost a sacred oratorio. It belongs in a series of solo Sonatas written by Poulenc to parallel a similar endeavour by Claude Debussy, but it is probably the best known of them all. Its intended recipients were, on the one hand, the Coolidge Foundation which had commissioned it, and, on the other, flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal who premiered it in 1957 in Strasbourg with Poulenc at the piano (they were immediately asked to encore the second movement!). Its American premiere took place on February 14th, 1958, at the Library of the Congress.

It is a piece deeply informed by Neo-Baroque traits, which paradoxically contribute to its modernity (acute listeners will actually spot a quotation from Bach’s Badinerie). There is a charming and slightly enigmatic first movement, a short but lyrical second movement, and a spectacular, funny and witty third movement.

With Johannes Donjon (1839-1912) we go back in time to a career which took place mainly in the nineteenth century. Similar to Widor, he was also born in Lyon; he had studied at the Paris Conservatoire under the guidance of Jean-Louis Tulou. Different from other composers recorded here, he was a flutist and wrote mainly for the flute. He is best remembered nowadays of his Cadenzas to Mozart’s D-major Flute Concerto, KV 314, and for this short but emotional Elegie. Intriguingly, the first edition of the piece indicates one “Robert” as the composer of the piano or harp accompaniment to the flute part, but no other information could be found about him. Certainly, however, the main focus is on the flute and on the beautiful decorative gestures it produces throughout the piece. The work is heralded by a poetical motto excerpted from the works by poet Jean Richepin: “Dans l’air obscurci / Les feuilles dernières / Roulent aux ornières. / Mon bonheur aussi” (“In the darkened air / The last leaves / Roll in the ruts. / My happiness too”).

The next item in this programme leads us to know Paul Taffanel not only as a legendary performer but also as a composer in his own right. His Andante pastoral et Scherzettino is a delightful pair of pieces, which belongs in a series of several short masterpieces which were commissioned by the Conservatoire to the leading musicians of the era, in order to employ them as morceaux de concours, i.e. compulsory new works which candidates to the final exams had to prepare. In this case, Taffanel wrote one such piece himself, in 1906: it would be the last piece he composed, dedicating it to his student Philippe Gaubert. With its combination of slow melodies and brisk staccatos, of sustained tones and light articulations, this pair of pieces assures the best opportunities for flutists to showcase their talent and skills.

Taffanel’s influence is also behind the composition of Jules Mouquet’s La flûte de Pan, a Sonata which is almost a suite in turn. It focuses on Pan, the Greek god of the pastures and of shepherding, who is always portrayed with the eponymous instrument he made out of the reeds in which the nymph Syrinx had turned herself in order to escape his unwanted attentions. Like Donjon’s Elegie, Mouquet’s piece has poetical mottos which explore and describe the piece’s mood. The first movement, “Pan and the Shepherds”, opens on this quotation: “Oh Pan living in the mountain, for us / with your sweet lips sing a song, sing it / for us accompanied by the shepherd’s pipe”. Musically, the god is portrayed in his natural setting by the first theme, and in his musical endeavours by the second theme.

The second movement, depicting the duet between Pan’s reeds and birdsong, has the following epigram: “Seated in the shade of this lonely wood / Oh Pan, how come you draw from your / pipe such lovely sounds?”. The movement faithfully represents what it promises, with sweetness and enchantment.

The third and last movement has a quote by Plato: “Silence, shady oaken glades! Silence, fountains sprouting from the rocks! Silence, sheep bleating near your young! Pan himself sings with his harmonious pipe, he has placed his moist lips on the set of reeds. Lightly treading around him, the water Nymphs and wood Nymphs dance together”. The alternation of happy, at times unrestrained dance of the nymphs with more subdued, lazy sections, contributes to the impression of spontaneity of this movement.

The programme is completed by another short gem, i.e. the Morceau de concours written by Gabriel Fauré. Similar to Widor, Fauré begam his musical activity as a church musician and organist, but later focused more pronouncedly on composition. This work belongs in a particularly fruitful and dynamic period of his life, where he was intervening loudly on his style. It was created, once more, as an examination piece for the Conservatoire, but it is impressive to note how many of the flutist’s skills are tested in such a short piece!

Together, these works are a brilliant demonstration of how flute music thrived in France between the nineteenth and twentieth century.

![Brian Lynch, Charles McPherson - Torch Bearers (2026) [Hi-Res] Brian Lynch, Charles McPherson - Torch Bearers (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/08/7w9gzslap9q13k2mlet4tfv7y.jpg)

![Brian Jackson & Masters At Work - EP Two (2026) [Hi-Res] Brian Jackson & Masters At Work - EP Two (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772621441_lhj1cghnuc4bc_600.jpg)