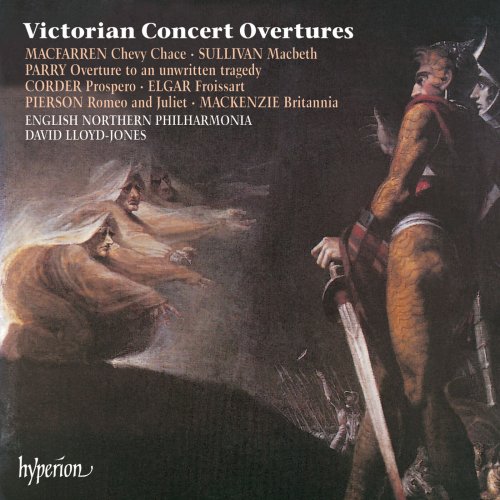

The Orchestra Of Opera North, David Lloyd-Jones - Victorian Concert Overtures (1991)

Artist: The Orchestra Of Opera North, David Lloyd-Jones

Title: Victorian Concert Overtures

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:06:52

Total Size: 249 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Victorian Concert Overtures

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:06:52

Total Size: 249 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Chevy Chace

02. Romeo and Juliet, Op. 86

03. Macbeth

04. Prospero

05. Froissart, Op. 19

06. Overture to an Unwritten Tragedy

07. Britannia "A Nautical Overture", Op. 52

The musical heritage of Great Britain is as long established as that of any European country and has enjoyed several golden eras. Nevertheless it has to be conceded that there was an awful ring of truth about the nineteenth-century German jibe ‘Das Land ohne Musik’ (‘the land without music’), for at that time British music had been at a low ebb since the death of Handel. Many reasons have been advanced to account for this and they point to one conclusion: what the Germans were essentially referring to as ‘music’ was opera and, more specifically, the genre that had grown out of opera—orchestral music. During the nineteenth century the German-speaking countries had a virtual monopoly of symphonic and orchestral music, and its influence on the rest of Europe was immense. Lacking a native operatic tradition, and thereby the organisations that engaged orchestras on a permanent basis, Britain was regrettably slow to turn to this rapidly developing medium.

Around the time of Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne things began to look up. In 1813 the Philharmonic Society had been founded by a group of musical enthusiasts in order to promote orchestral concerts. In 1822 the Royal Academy of Music was established, and not surprisingly many of the composers who were to rouse the country from its orchestral torpor were trained there. The composer of the first of the overtures on this CD is a case in point. Despite his Scottish name, Sir George Macfarren (1813–1887) was of English descent and born in London. At the age of sixteen he entered the newly opened RAM where Sterndale Bennett was a fellow pupil, and he went on to become not only a prolific composer in all forms (his cantata May Day and opera Robin Hood achieving notable success) but also a pillar of the British musical establishment. In 1860 he went prematurely blind, yet for the last eleven years of his life he was both Principal of the RAM and Professor of Music at Cambridge.

The overture Chevy Chace (Macfarren was meticulous in preferring the antiquated spelling of the latter word) dates from 1836, and although its origins were theatrical it quickly became accepted as a concert overture in its own right and was frequently performed during the composer’s lifetime. It had been commissioned by an impresario when a prelude to a melodrama of the same name by James Planché (librettist of Weber’s Oberon) was required in a hurry. Chevy Chace was a popular old ballad recounting a feud between the families of Percy and Douglas over hunting rights on the Scottish border, and was sung to three different tunes. Macfarren’s choice is wistfully announced on divided violins in the slow section that follows the opening ‘Allegro vivace’. The scoring and rhythm of the all-pervading dotted hunting motif show that the Philharmonic Society’s performances of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony had left their mark on at least one listener. The Chevy Chace tune is later skilfully worked into the main section of the overture which is scored with a surprisingly resourceful use of percussion.

In the event, the overture was not used in the play’s production but was first performed in its own right in 1837. It was conducted by J W Davison, who was to become better known as the redoubtable music critic of The Times. Six years later Mendelssohn conducted it at the Leipzig Gewandhaus and wrote a letter to Macfarren describing its enthusiastic reception. More surprisingly, another German composerconductor gave it its next London performance in 1855 at a Philharmonic concert. This was none other than Richard Wagner who, in his autobiography My Life, calls the composer ‘Mr. Mac Farrinc, a pompous, melancholy Scotsman’, misnames the overture ‘Steeple-Chase’ but admits to having enjoyed it for its ‘peculiarly wild, passionate character’—a generous assessment from someone who had already written the Prelude to Act 3 of Lohengrin. Chevy Chace has never been published in full score, but it 1841 it was issued as a piano duet.

The overture—and more specifically the concert overture as developed by Beethoven, Weber and Mendelssohn—from now on became the most favoured form for British composers to use when venturing into the field of orchestral music. Shorter, less demanding than the symphony and allowing the possible further stimulus of a dramatic or pictorial programme, the term ‘overture’ in the mid-nineteenth century had come to be used for almost any one-movement orchestral piece with a more or less descriptive title. Even Liszt’s earliest orchestral works had been conceived as concert overtures until on publication they established a new vogue term ‘symphonic poem’. In England, Macfarren’s colleague, Sterndale Bennett, produced three examples in the Mendelssohnian mould which were to set a pattern, if not a standard, for several years to come.

One figure who stood apart from the new generation of composers emerging from the RAM was Hugh Pearson, who spent most of his adult life in Germany where he altered his name to the more teutonically acceptable Hugo Pierson (1815–1873). Harrow and Cambridge educated, Pierson undertook his musical studies in Germany and after a short period as Reid Professor of Music in Edinburgh, returned there for the remaining years of his life. His very individual, even idiosyncratic, idiom and allegiance to the New German school of composition never endeared him to the Mendelssohn-worshipping British musical establishment, but he found widespread favour in Germany where the success of his many fine songs and music for Faust greatly added to his reputation.

The concert overture Romeo and Juliet, probably composed in the mid-1860s, was published in Leipzig a year after his death and first heard in Britain at a Crystal Palace Saturday Concert. Whereas his symphonic poem Macbeth is provided with extensive stage directions and quotations, and his Schiller overture The Maid of Orleans prefaced by a detailed explanation of each section, Romeo and Juliet lacks any such guidance. Nevertheless it is not difficult to recognise Romeo himself in the brooding appassionato descending figure given to the lower strings and bassoon at the opening, and Juliet in the graceful, artless motif that follows. Stately tutti sections give a flavour of Verona’s rich festivities, and Romeo’s wooing of Juliet is also to be recognised in the many question-and-answer phrases. All this is expressed in short, pregnant musical ideas which follow one another at an almost disconcertingly kaleidoscopic speed. Pierson’s rhythmic variety and piquant use of the orchestra have sometimes been compared with that of Berlioz, and his music certainly exhibits a fresh, unfettered imagination that has earned him the reputation of one of the few avant-garde British composers of this period.

Although originally written at the same time as the incidental music to Irving’s 1888 production of the play, the fine Macbeth overture by Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) is a concert overture in all but name, and was doubtless revised before its publication six years later, as the Lyceum pit can hardly have contained so large an orchestra, complete with tuba and harp. Composed at a time when Sullivan was at the height of his powers—between The Yeomen of the Guard (1887) and The Gondoliers (1890)—the overture aims at a closely knit musical structure rather than the loosely assembled string of melodies that he usually provides. Although the benevolent influence of Schubert and Mendelssohn can still be felt, there are strikingly successful evocations of the grim northern setting of the play (broad unison phrases), Banquo’s ghost (an eerie, harmonically strange passage for flute and strings), regal glory, the witches and, in the most characteristically broad tune, the figure of ‘gracious Duncan’. All this is expertly conceived with Sullivan’s usual technical mastery and command of orchestration.

Frederick Corder (1852–1932), who studied at the RAM and later with Ferdinand Hiller in Cologne, became an energetic and respected figure of the late Victorian musical scene. Despite a wide range of compositions, including songs, operas and the inevitable religious cantatas commissioned by provincial festivals, his name is now chiefly remembered as the first translator of the mature Wagner operas. As professor and curator at the RAM he also became the teacher of a later generation of composers including Bantock, Holbrooke and Bax. The concert overture Prospero, published in the year of Sullivan’s Macbeth, shows a welcome change of direction in the continental influences that were gradually beginning to fertilize British orchestral thinking. Doubtless influenced by his time in Cologne, Corder became an ardent follower of the Liszt/Wagner school and even wrote a book on the former composer. The opening Wotanesque tread of trombones and its ethereal pendant on flute, harp and solo violins immediately proclaim a desire to use orchestral sonority in its own right rather than as organ registration transferred to the orchestra. Despite this opening theme, which can be associated with the stern, yet noble figure of Shakespeare’s last great creation, it would be wrong to search for explicit programmatic features in the overture since much of the music is believed to have been originally composed for a different purpose. Instead it represents an impressive essay in almost abstract musical thought conceived with the sonority of the New German school of orchestration in mind. During Corder’s lifetime the overture was frequently performed, notably by Sir Henry Wood.

Far removed from London musical institutions and Continental conservatories was an intense, poetic, entirely self-taught aspiring composer in Worcester who in today’s parlance would be described as a peripatetic violin teacher. In a letter dated 1 January 1890, Edward Elgar (1857–1934) was invited to write an orchestral work for that year’s Three Choirs Festival in Worcester. This had undoubtedly been provoked by the rapidly growing local reputation he was gaining as player, composer and conductor, yet even so it was a bold choice. Elgar decided on the form of a descriptive overture (Cockaigne and In the South were to follow) and, fired by references in Scott’s Old Mortality to the medieval chronicler Froissart, he started work in April, prefacing the score with a quotation from Keats: ‘When Chivalry lifted up her lance on high’.

Yet it was probably the two most significant events of the previous year that prompted the 32-year-old composer to undertake this idealised portrait of knightly valour and fidelity to a lady-love: his marriage, and the overwhelming impression created by performances at Covent Garden of Die Meistersinger. The arresting opening of Froissart has the unmistakable imprint of Elgar, but the jaunty, dotted ‘knightly’ figure that pervades much of the overture’s thematic material can be traced back directly to the music with which Walther von Stolzing is introduced to the assembled mastersingers. Two things immediately impress in this astonishingly assured first essay in extended form: the music’s characteristic blend of ebullience and wistfulness, and the orchestration which already has in embryo all the distinguishing features that were so soon to earn the epithet ‘Elgarian’. The composer retained a lifelong affection for the work: revising the score for publication in 1901 he wrote to his friend Jaeger: ‘What jolly healthy stuff it is—quite shameless in its rude young health!’.

Froissart was well received by public and press. Nevertheless Elgar was not asked to to provide a new work for the next Worcester Festival in 1893; that honour went to the established composer of four symphonies and innumerable choral works, Hubert Parry (1848-1918). Parry had not only studied at the RAM with Sterndale Bennett and Macfarren, but had spent one of his Cambridge long vacations in Stuttgart taking lessons from Pierson. He produced an Overture in A, ‘to an Unwritten Tragedy’, and at its first performance Elgar was obliged to earn his livelihood among the first violins. The juxtaposition of the words ‘overture’ and ‘tragedy’ inevitably recall Brahms, whose current influence on British music was a logical extension of that of Mendelssohn.

Parry was later to write the article on Brahms in Grove’s Dictionary where he defended the very position he himself appears to adopt in this work: ‘He seems to have set himself to prove that the old principles of form are still capable of serving as the basis of works which should be thoroughly original both in general character and in detail of development without … falling back on the device of programme’. Despite the conservative cast of the music and general sobriety of orchestration, the overture has a distinctive noble dignity. The surprisingly prevalent use of the major mode to depict tragedy has a classical precedent in Gluck, and it is this feature that contributes most to its essentially British character.

Parry’s overture was given its first London hearing at a Philharmonic Society concert the following April under the baton of the Scottish composer and conductor Alexander Mackenzie (1847–1935). Trained at the RAM, Mackenzie had started life as an accomplished professional violinist but went on to become one of the most prolific and influential musicians in British musical life. It was possibly the orchestral connection that instilled in Elgar a lifelong affection and admiration for the older composer. Sitting in the last desk of first violins at the 1881 Worcester premiere of Mackenzie’s cantata The Bride, Elgar was overcome by its masterly orchestration and later wrote: ‘The coming of Mackenzie, then, was a real event. Here was a man fully equipped in every department of musical knowledge who had been a violinist in orchestras in Germany. It gave orchestral players a real lift’.

Mackenzie succeeded Macfarren as Principal of the RAM in 1881 and composed his ‘nautical overture’ Britannia for the festivities connected with the seventieth anniversary of that institution in 1894. It was given its first public London performance in May of the same year under Richter and soon became a regular feature of the Henry Wood Proms. The overture makes witty and ingenious use of the refrain to Arne’s famous tune and to certain melodic features of the hornpipe ‘Jack’s the Lad’, but is largely composed of three original themes, one of which (the trio-like second subject) is intended to reproduce the style of nautical song popularised by Dibdin. The whole piece is put together with the professional assurance so admired by Elgar and seems to look forward to the salty tang of Walton’s Portsmouth Point. Coincidentally, both overtures were inspired by the work of an English caricaturist—in this instance Cruikshank’s ‘Saturday Night at Sea’. It is the very epitome of the robust good health in which British orchestral music at last found itself in the final decade of Queen Victoria’s reign.

![Lis Wessberg - Longing (2026) [Hi-Res] Lis Wessberg - Longing (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/25/7dwhqxm5lzisnmzh5tk0htv7a.jpg)