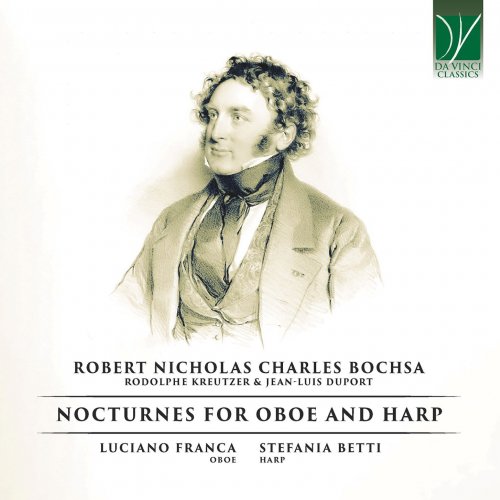

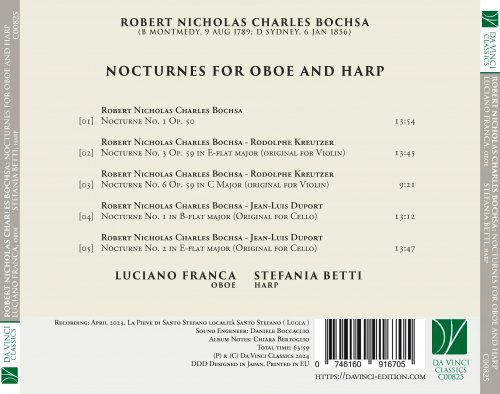

Luciano Franca, Stefania Betti - Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa: Nocturnes for Oboe and Harp (2024)

Artist: Luciano Franca, Stefania Betti

Title: Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa: Nocturnes for Oboe and Harp

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:59

Total Size: 256 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa: Nocturnes for Oboe and Harp

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:59

Total Size: 256 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Nocturne No. 1, Op. 50

02. Six Nocturnes Concertants, Op. 59: No. 3 in E-Flat Major

03. Six Nocturnes Concertants, Op. 59: No. 6 in C Major

04. 3 Nocturnes en Duo: No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Lento (Original For Cello)

05. 3 Nocturnes en Duo: No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Allegro moderato (Original For Cello)

The irony of the programme recorded on this Da Vinci Classics album is that, on the one hand, it is made nearly exclusively of collaborative works; on the other, that there is one clear protagonist, and this is Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa.

The idea of a collaborative classical music work may at first strike the reader as unusual. The concept of authorship is in fact deeply ingrained in our understanding and appreciation of classical music. Many music lovers are keen to test their own knowledge of musical style and history by attempting to guess who composed the piece played on the radio at a given moment; music teachers frequently (and rightfully) encourage their students to acquaint themselves with the biography and culture of a given composer, claiming that this will help them to better understand his or her works.

Doubtlessly, there is a connection between a person’s life, context, relationships and education on the one hand, and the music they wrote on the other. However, frequently the link is much less evident than one might suppose: composers at a particularly joyful or difficult moment of their lives can write musical works which express exactly the opposite mood. The very idea that music expresses its composer’s feelings is a relatively recent concept, and one which is highly indebted to Romantic ideals (and myths).

Furthermore, it is not too far-fetched to say that most music played around the world in the history of humankind is the fruit of multiple authorship, and in most cases there is not a single name which can be associated to a particular melody or piece. In other cases, a “composer” may lend his or her name to a piece, but he or she is just the last one to have assumed and resumed a tradition which may go back to several centuries earlier. These are the cases with most pieces belonging in the oral tradition, which, as said, comprises in itself most of the music heard or played worldwide.

The case with the works on this album is different, since here we do have two (or three) names, and each is very important in his own field. However, since these composers were active in the Romantic era when the association between musicians and their oeuvre seems so inseparable, the very existence of these pieces may lead listeners to some wonder.

In fact, these examples were far from unique. Perhaps, our impression is due to the fact that such collaborative works have de facto virtually disappeared from the concert stage. Musicians do perform pieces with two names before their title, but these normally are transcriptions or arrangements: for instance, works by Bach/Busoni are original works written by Bach in the eighteenth century and then “translated” for another instrumental medium by Busoni in the twentieth century. Different is the case of works jointly conceived by two or more musicians who knew each other and deliberately decided to cooperate for the creation of new works.

One of the musicians featured in this album, i.e. Kreutzer, had a particular penchant for this kind of collaborations. Rodolphe Kreutzer had been born in Versailles in 1766 (so he was Mozart’s junior by ten years), and received his first musical instruction as a violin player from his father, later to continue under the guidance of Anton Stamitz. A child prodigy, already at 16 Kreutzer was able to replace his father as the Concertmaster of the Royal Chapel, and later at the orchestra of the Italian Opera in Paris. Having met there the Italian violinist and composer Giovanni Battista Viotti, Kreutzer was both inspired and encouraged by his colleague to undertake an activity as a composer beside that of a performer. Still, Kreutzer lacked formal training in composition, and this is perhaps one reason why he was so keen to cooperate with others. It is likely that Kreutzer had many brilliant and tuneful musical ideas, but he perhaps felt slightly insecure on how to develop them on a large scale, and/or as concerns aspects of the musical language which need thorough training (such as contrapuntal or harmonic writing). His atypical education, however, did not prevent Kreutzer from writing a large corpus of major works, including symphonies, concertos, operas, and (the output for which he is best remembered today) some excellent and indispensable violin Etudes. In fact, along with his Etudes, another reason why the name of Kreutzer has achieved immortality in the musical world is his being the dedicatee of Beethoven’s most demanding and impressive violin Sonata, after which a novel by Tolstoy was fashioned (and a Quartet by Janacek was composed on Tolstoy’s tale!). Some of Kreutzer’s most notable collaborations include those with Luigi Cherubini, Ferdinando Paër and others, but his musical partnership with Nicholas Bochsa is certainly one of the most fruitful among the several he entertained.

Actually, Bochsa provides evidence to what had been said above about the unrelatedness of a musician’s biography and works. Nocturnes constitute a substantial and celebrated portion of his overall output; yet, few biographies are as far from the Nocturnes’ tranquility, calm, and contemplativeness than Bochsa’s.

Similar to Kreutzer, but even more than his colleague, Bochsa had been a child prodigy, especially in consideration of the fact that he was an impressive poly-instrumentalist who was capable of performing several different instruments as a virtuoso since a very young age. He composed works for his own performances already as a child; when he was eventually admitted at the Conservatoire of Paris he graduated with a premier prix in composition in just one year. But at the Conservatoire he discovered, or was finally able to know more deeply, the instrument to which his fame would be lastingly bound, i.e. the harp. Bochsa in fact became enthralled with the harp, and would also contribute profoundly to the development of new techniques in instrument-building, paving the way for the modern concert harp.

His activity as a composer brought him to the highest levels of the French society of his time. Thanks to a timely celebratory work about Napoleon, he became the Emperor’s favourite musician, but, uncharacteristically, Bochsa was able also to survive Napoleon’s fall, and to be held in equal favour by the restored sovereign of France. Bochsa’s income became extremely high for a musician, but, unfortunately, his lifestyle fairly exceeded even the very large means at his disposal.

Instead of economizing, however, Bochsa had the brilliant idea of forging documents, signing them in the name of his friends, acquaintances, and mentors, in order to obtain the funds he needed. His game was discovered, however, and he was condemned to many years of forced labour. He somehow managed to escape justice, fleeing to England, where he was able to rebuild his fortune and to gain acceptance in the highest spheres of the British nobility. His lessons and his concerts made the harp so fashionable that playing it became a distinctive trait for aristocratic people.

However, even this was not to last: information about his dealings with French justice reached the noble ears of his patrons, and a scandal ensued; a scandal which was only reinforced by Bochsa’s elopement with a colleague’s wife, who was also a very good singer herself.

The adulterous couple travelled through most of Europe and in America (including the US and Mexico), giving concerts which granted them great success; they eventually got to Australia, where Bochsa’s adventurous life came to an end, to the sincere grief of his companion, who had a beautiful monument built in his honour in Sidney.

In spite of the undeniable dark sides of his life, Bochsa was a great musician and one who was capable to promote his instrument and its literature, also thanks to his cooperation with other musicians such as violinist Kreutzer and cellist Duport.

The Nocturnes Concertants op. 59 are a splendid example of how the talents of two great musicians can produce something unique, and surprisingly unified. Both instruments are treated as peers, and the hand of composers who were also virtuosos of their respective instruments is clearly discernible. Significantly, Bochsa and Kreutzer refrained from merely considering the harp as the violin’s accompanist; the two instruments are perfectly integrated, and it is not infrequent that the main theme be entrusted to the harp.

These Nocturnes are less spiritual and transcendent than those by Chopin; however, they are delightful pieces, full of atmosphere, delicacy, refinement, lyricism, and intensity. These same qualities also apply to the Nocturnes realized by Bochsa jointly with Jean-Louis Duport, who, similar to both Bochsa himself and to Kreutzer, is a composer whose Etudes are still abundantly employed in the training of young musicians.

Considering, therefore, that the three musicians represented here were all absolute masters of their instruments, and among the greatest virtuosos of their times, it may strike the reader as unusual that such idiomatic works be transferred to a completely different sound medium: from bowed string instruments such as the violin and the cello to a wind instrument as the oboe.

While it is true that all musicians took into great consideration the idiomatic traits of their instrument, it is however also true that they were artists of genius, and that their melodies and musical gestures bear effortlessly the challenge of such changes of destination. Indeed, the fact that the oboe is played through breathing almost enhances the vocal component of this music, which, indeed, is so powerfully indebted to the belcanto tradition and to the operatic gestures of nineteenth-century music that its music becomes a real “song without words”.

![Rafael Riqueni - Nerja (2025) [Hi-Res] Rafael Riqueni - Nerja (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1768128135_qy2pif80oj6rgensavcl1j1kb.jpg)

![Jake Baxendale - Gardening Music, Volume 1 (2025) [Hi-Res] Jake Baxendale - Gardening Music, Volume 1 (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/12/h1xq4dp1lh5mal47e7fhs2e8t.jpg)