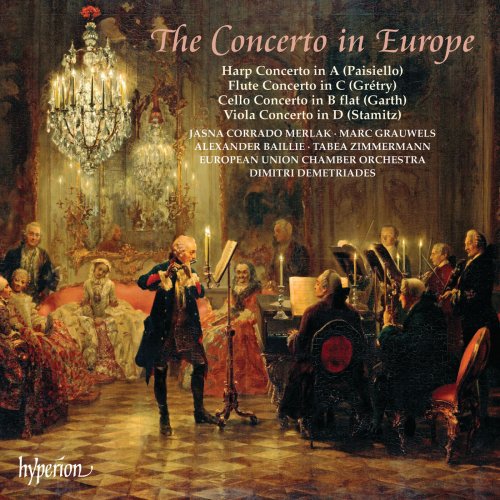

European Union Chamber Orchestra, Dimitri Demetriades - The Concerto in Europe: Paisiello, Grétry, Stamitz & Garth (2000)

Artist: European Union Chamber Orchestra, Dimitri Demetriades

Title: The Concerto in Europe: Paisiello, Grétry, Stamitz & Garth

Year Of Release: 2000

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:58:03

Total Size: 239 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: The Concerto in Europe: Paisiello, Grétry, Stamitz & Garth

Year Of Release: 2000

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:58:03

Total Size: 239 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Harp Concerto in A Major: I. Allegro

02. Harp Concerto in A Major: II. Larghetto

03. Harp Concerto in A Major: III. Rondo. Allegro vivace

04. Flute Concerto in C Major: I. Allegro

05. Flute Concerto in C Major: II. Larghetto

06. Flute Concerto in C Major: III. Finale. Allegro

07. Cello Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major: I. Allegro moderato

08. Cello Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major: II. Affettuoso

09. Cello Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major: III. Allegro assai

10. Viola Concerto in D Major, Op. 1: I. Allegro, non troppo

11. Viola Concerto in D Major, Op. 1: II. Andante moderato

12. Viola Concerto in D Major, Op. 1: III. Rondo. Allegretto

Of the four instruments represented on this record, only the flute regularly featured soloistically in the late eighteenth century. These four works also offer an unusual aspect of their authors’ work as each of the composers was best known in other musical fields: Paisiello and Grétry were opera composers, Stamitz was above all a symphonist, and Garth wrote mainly church music. The scale of each concerto indicates the relative importance of form, structure, melody and harmony, as was characteristic in each of the countries, and perhaps even suggests the lifestyle of the men who wrote and played the works.

It is unexpected therefore that, with the exception of the Englishman, all our composers travelled extensively outside their own countries to wherever their work took them. England was naturally cut off from the mainstream, and the interest of John Garth’s compositions (he actually wrote six cello concertos) must therefore be in their individual spirit, a natural but perhaps uncultivated vigour. The mainland European composers by contrast were subject to many influences, both musical and social, and this cross-fertilization surely had its effect. Did Paisiello try to popularize Italian music at the court of St Petersburg in 1776, and Carl Stamitz convert the same people to a Teutonic style in 1790, for example? Or did the courts simply like variety? Both Paisiello and Stamitz also went to Paris, which prided itself on being the great musical centre, and Grétry actually settled there.

Born in Liège with an eye for fame and fortune, Grétry learned his skills in Rome and quickly moved to the fashionable Parisian environment where he popularized the Italian style of opera. His mission was to enforce the expression of words by melody, and he was fortunate in making friends with influential literary men and in gaining powerful patrons. Paisiello was also treated with magnificence by Napoleon, but he determined to return from his travels to Naples, the home of natural song. His reputation was of course also built on his operas, of which there are at least a hundred, all of them musically charming and graceful, but simplistic.

We look to Germany to find the real home of instrumental music, and indeed to find an interest in abstract musical structure and the subsequent development of the concerto form. Carl Stamitz was the most famous of his Bohemian family, all of whom contributed to the innovations of the Mannheim School. To them we owe the development of instrumental expression, and hence of the orchestra itself as we know it today. Stamitz’s Concerto Op 1 for viola has gained a rightful place in the standard viola repertoire. In proportions both formal and musical, it is weighty as befits a composer of some seventy symphonies and a dozen other concertos. It makes use of an extended sonata-form first movement, allowing the viola full use of its expressive and virtuosic range. Interestingly, as if to balance the mellow sound of the viola, there are clarinets instead of oboes in the orchestra.

Paisiello’s concerto is one of a set of keybord concertos, but adapts beautifully to the harp. Simple in form, it is rich in colour. Of its three movements, the second seems to make an emotional centre, emerging plaintively from an intimate stage, for which a setting is presented by the first movement, and which the last movement playfully offsets. Grétry’s concerto also reminds us, in the tuttis of the outside movements at least, of an operatic stage, but one in a rather different world. The music in C major is optimistic and determined, as were many of the operas Grétry wrote for Paris, and the role of the flute is that of a hero, or protagonist. We are left to speculate on the motivation for the concerto by the church-composer, John Garth. With its robust writing for the cello, it provides us with a good example of how concerto form in the eighteenth century developed from the Baroque concerto grosso.

![Sonny Stitt - A Tribute To Duke Ellington (With Strings) (2026) [Hi-Res] Sonny Stitt - A Tribute To Duke Ellington (With Strings) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1768738436_cover.jpg)

![Vance Thompson - Lost and Found (2026) [Hi-Res] Vance Thompson - Lost and Found (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1768569026_cover.jpg)