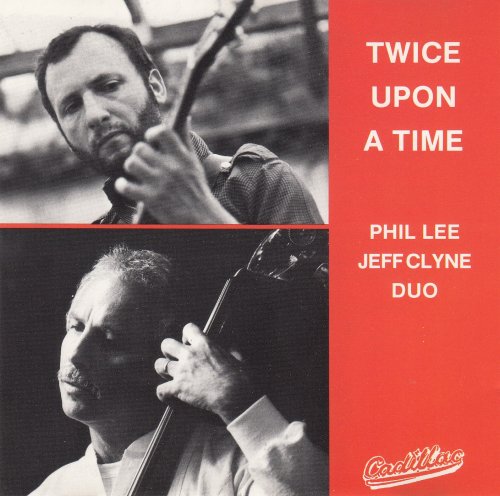

James Bowman, David Miller, The King'S Consort - Dowland: Awake, Sweet Love (1991)

Artist: James Bowman, David Miller, The King'S Consort

Title: Dowland: Awake, Sweet Love

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:12:18

Total Size: 264 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Dowland: Awake, Sweet Love

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:12:18

Total Size: 264 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Can She Excuse My Wrongs?

02. Author of Light

03. Flow, My Tears

04. A Fancy

05. Come Tread the Paths

06. Since First I Saw Your Face

07. Sorrow, Stay, Lend True Repentant Tears

08. The Most Sacred Queen Elizabeth, Her Galliard

09. Eliza Is the Fairest Queen

10. Eyes, Look No More

11. Oft Have I Sigh'd

12. Go Nightly Cares

13. Pavin

14. Thou Pretty Bird, How Do I See

15. In Terrors Trapp'd

16. Now, Oh Now I Needs Must Part

17. Preludium

18. A Fantasie

19. Say, Love, If Ever Thou Didst Find

20. I Die Whenas I Do Not See

21. The Frog Galliard

22. Awake, Sweet Love, Thou Art Returned

23. Tell Me, True Love

The latter part of Queen Elizabeth’s reign has often been described as the beginning of a ‘Golden Age’—forty years in which England gave the world Marlowe, Webster and Bacon, the prose of Sir Walter Raleigh, the Authorized Version of the Bible, the scientific researches of Gilbert and Harvey, and the music of Byrd, Dowland, Gibbons, Morley, Weelkes, Wilbye and many more. This intellectual and artistic excellence seemed to flower with the national self-confidence that followed the defeat of the Spanish Armada, ushering in an age when music and the theatre became a regular part of life, not only at the Royal Court, but for a larger proportion of the population than ever before, and one that continued, albeit declining quite quickly, after the death of Elizabeth.

Amateur music-making in England was never a more requisite social grace than it was under the Virgin Queen. ‘Taught music early in life’, as Burney noted, Elizabeth ‘continued to amuse herself with music many years after she ascended the Throne’ and, in doing so, set an example which was followed in households throughout the country. The Queen’s enthusiasm was not entirely for her own amusement, for she was quick to seize the political capital which could be made out of a lavish entertainment, particularly when laid on for a foreign dignitary, but the example which she set, as performer (who played the virginals, according to Sir James Melville, ‘excellently well’) and as patron, albeit one who employed many more foreigners than Englishmen, paved the way for an age which saw a wealth of musical achievements.

The great demand by amateurs for printed music, coupled with growing improvements in music publishing, saw the production of a large number of collections of music, and as the possibilities of publishing music improved, so did the composers’ interest in tempting the customers. The instruments of the amateurs were the viol, the lute, keyboard instruments and, of course, the voice. Most sizeable households owned a chest of viols, and the lute was even more universal. The voice, with the rise of the lute song and the madrigal, allowed the participation of men, women and even children, and music-making flourished as it never had before.

John Dowland’s Firste Booke of Songes or Ayres, printed in 1597, marks the start of the published lute song, and a landmark in an extraordinarily fertile period in English musical history. Over the next twenty-five years around thirty volumes of lute songs were printed, containing works by numerous talented English composers. The songbooks had great popular appeal not only for their musical content, but also because of their economy for home performance: four or five performers could sit around a table and read off the one book. The lute songs could be performed by a solo voice with lute or orpharion, with or without bass viol, or by four voices with or without instruments.

The consort song was popular for similar reasons. This was a form which can be dated back maybe as early as 1550 and (unlike the madrigal and ayre which were indebted to foreign examples) was an English invention which involved one or sometimes two voices with an accompaniment of viols in a texture which was usually five-part. Where the lute song was attractive for its intimate pairing of voice and accompaniment, the consort song had the benefit of an accompaniment of arguably the most vocal and expressive family of instruments ever devised.

The rise in popularity of the Renaissance lute among the leisured classes towards the end of the sixteenth century resulted in the publication of a number of lute tutors, which also contained music for the student to play. One of the last of these to be published was Robert Dowland’s Varietie of Lute-Lessons of 1610 which contained a translation of the instructions given in Besard’s Thesaurus harmonicus (1603) and further observations by Robert’s distinguished father, John Dowland. Most of the lute solos contained on this disc are taken from this publication, which contains not only a selection of fantasias, pavans, galliards, voltes, almains and corrants collected by John Dowland on his Continental travels, but also prime sources of nine of Dowland’s best solo pieces.

The first definite information we know of John Dowland (1563–1626) comes from 1580 when he began four years in Paris as ‘servant’ to Sir Henry Cobham. In July 1588 we know he gained his BMus from Christ Church, Oxford, and in 1590 we hear for the first time of his music: in 1592 he played before the Queen at Sudeley Castle. In 1594, apparently in a fit of pique at being refused in his application to become the Queen’s lutenist, Dowland decided to travel abroad. His journeys took him first to the court of the Duke of Brunswick, and then on to Kassel where the Landgrave of Hesse offered him a post. This post was refused, and Dowland travelled on to Italy, visiting Venice, Padua, Ferrara and Florence (which he left hurriedly when he realized that he had became entangled with a group of exiled Catholics plotting the assassination of Queen Elizabeth). Henry Noel, a favourite courtier of the Queen, wrote to Dowland advising him to return to England, stating that the Queen had asked for him, but Dowland’s return, probably in late 1596, came too late, for Noel died before pleading the composer’s case with the Queen, and once again Dowland was without the appointment he so wanted. In 1597 Dowland collected together twenty-one of his songs and published them. The Firste Booke of Songes or Ayres was enormously popular, and was reprinted four or five times.

In 1598 the Landgrave of Hesse, hearing of Dowland’s lack of success in securing an English court post, invited him to Kassel, but by the end of the year it was at the court of Christian IV of Denmark that he was finally in a salaried post (and at an especially high salary). At first all went well, and The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres was sent to England and published in 1600, followed by The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires in 1603. By now, despite the success of his compositions, Dowland was accumulating debts in Denmark: later in 1603 he returned to England, staying for over a year, and played before Queen Anne. During this time he published his extraordinary Lachrimae, or Seaven Teares. He returned to Denmark in 1605, but the debts were still rising, and by the time he was finally dismissed in March 1606, he was basically penniless. Although other compositions still emerged, notably the collection of 1612 A Pilgrimes Solace, Dowland’s disappointment at his failure to gain a court post in his own country appears to have soured the urge to compose. Even when in 1612 he was finally appointed one of the King’s Lutes, few further compositions emerged and, although given a doctorate in 1622, and finally receiving the accolade of being one of the finest of his profession, he seems to have died a disappointed man.

Although Dowland is reported to have been ‘a cheerful person’, and some works show this side of his character, his music is full of preoccupations with darkness, tears, sin and death: this intense and tragic melancholy pervades much of his output. His music for solo lute shows writing of great individuality, as well as a consummate mastery of the instrument shown by few of his contemporaries, but it is in the lute songs that his genius emerges most strongly. His astonishing grasp of harmony (especially his use of chromaticism and biting discords), his memorable melodies and outstanding ability to set words ensured that he is now regarded as the greatest exponent of his art.

Thomas Campion (c1567–1620) was among the most prolific of the English lute-song writers, with around 120 extant songs to his credit. Among his contemporaries he was unique in writing all his own texts. He studied both at Cambridge (where his interest in medicine appears to have been stimulated) and in France, receiving a degree from the University of Caen in 1605. During his lifetime he achieved fame as both poet and composer, and from 1607 was one of those who supplied texts and music for the lavish masques and entertainments provided for James I. His first published songs were printed by Rosseter in 1601, but it was not until 1613 that his first two Bookes of Ayres appeared in print, followed four years later by the third and fourth volumes. The quality of his lute songs was variable (he wrote only in this genre), but his understanding of the English language gave him a remarkable ability to match the rhythms of his words with music: at his best he was also a remarkable and elegant melodist.

John Danyel (1564–1626) is one of the most unjustly ignored composers of the age. We know surprisingly little about his life, but he is recorded as having received his BMus from Christ Church, Oxford, in 1603: we know of a publication of his in 1606, that he received livery as a musician of the royal household in 1612, that he is mentioned in connection with running theatre companies in 1615 and 1618, and that he was one of the royal musicians at the funeral of James I in 1625. Despite this scarcity of information, Danyel appears to have been held in high esteem by his contemporaries, and the relatively small amount of his music that survives demonstrates a fine ability for word-painting, as well as considerable skill at writing for the lute.

Thomas Ford (d1648) was appointed one of the musicians to Prince Henry in 1611, later becoming one of the lutes and voices to Prince Charles, serving him up to 1642. However, Ford’s lute songs date from before 1607, when his Musicke of Sundrie Kindes was published in London. Among all his varied music, which contains anthems, consort music and lyra viol duets, as well as lute and consort songs, it is in the lute songs that we find Ford at his most effective and charming.

Alfonso Ferrabosco (1543–1588) was born and died in Bologna, but spent much of his working life in the service of Elizabeth. He seems to have been quite a controversial figure, not always popular with his colleagues at the English court. His popularity with Elizabeth, who paid him handsomely for his musical services, may have led to the theory that he was a secret service agent for the Queen, but there is, perhaps sadly, little genuine evidence for this.

William Hunnis (d1597) was a mysterious figure and a zealous Protestant who, despite being implicated and imprisoned in 1556 for plots against the Catholic regime, managed to escape execution, and was indeed restored to his former position as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal by Queen Elizabeth. He was given other appointments too, including that of Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal. Besides his musical commitments he was a considerable poet whose works were used in verse anthems by Morley, Weelkes and Mundy. His musical compilation Seven Sobs of a Sorrowfull Soule for Sinne was reprinted no fewer than fourteen times between 1583 and 1636.

Little of the music of Edward Johnson (fl1572–1601) survives, though he was highly regarded by his contemporaries. He received a MusB from Cambridge late on in his life, and Morley’s esteem for him was great enough to ask him to contribute to The Triumphes of Oriana (1601). William Byrd transcribed a pair of his dances for keyboard. Queen Elizabeth is reported to have been so delighted with her first hearing of Eliza is the fairest Queen that she demanded it be played twice more.

![Criolo, Amaro Freitas, Dino D'Santiago - CRIOLO, AMARO E DINO (2026) [Hi-Res] Criolo, Amaro Freitas, Dino D'Santiago - CRIOLO, AMARO E DINO (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/17/usrf0slui6mhit9yit6clcqw9.jpg)

![Billy Martin, Matt Glassmeyer, Jonathan Goldberger - State Fête (2026) [Hi-Res] Billy Martin, Matt Glassmeyer, Jonathan Goldberger - State Fête (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/17/u0qd21dtfeg13eogj3a9ybwsz.jpg)