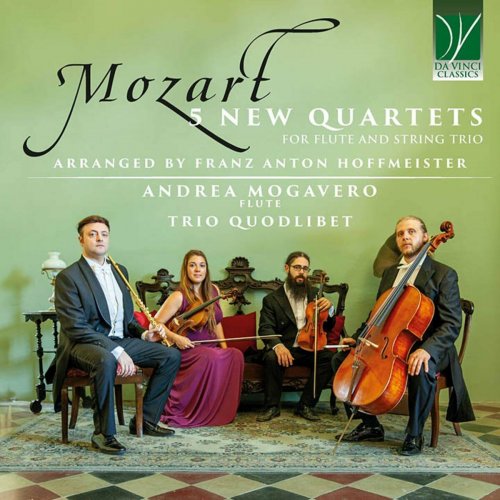

Andrea Mogavero - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: 5 New Quartets for Flute and String Trio (2024)

Artist: Andrea Mogavero, Trio Quodlibet

Title: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: 5 New Quartets for Flute and String Trio

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 85:41 min

Total Size: 373 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: 5 New Quartets for Flute and String Trio

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 85:41 min

Total Size: 373 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.1 in F Major, K.370: I. Allegro

02. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.1 in F Major, K.370: II. Adagio

03. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.1 in F Major, K.370: III. Rondeau. Allegro

04. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.2 in C Major, K. 309: I. Allegro con spirito

05. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.2 in C Major, K. 309: II. Andante un poco adagio

06. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.2 in C Major, K. 309: III. Rondo. Allegretto grazioso

07. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.3 in F Major, K.533: I. Allegro

08. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.3 in F Major, K.533: II. Andante

09. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.3 in F Major, K.533: III. Rondo. Allegretto

10. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.4 in D Major, K.311: I. Allegro con spirito

11. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.4 in D Major, K.311: II. Andante con espressione

12. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.4 in D Major, K.311: III. Rondo. Allegro

13. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.5 :Alla Turca: in A Major, K.331: I. Andante grazioso

14. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.5 :Alla Turca: in A Major, K.331: II. Menuetto & Trio

15. Quartet for Flute and String Trio No.5 :Alla Turca: in A Major, K.331: III. Alla Turca

Mozart’s last opera is The Magic Flute: its true protagonist, in fact, is neither Tamino or Papageno, or Sarastro, but rather the magical instrument which binds the various characters of the plot as if through a chain of music. To the flute, therefore, Mozart entrusted some of his most beautiful late melodies, including that of Tamino’s aria, Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton, whose very lyrics seem to be meta-musical and meta-theatrical: the composer’s music praises his own music and the enchanted sound (“Zauberton”) of the flute. In spite of this, Mozart was not particularly fond of the flute’s timbre. Among the wind instruments, his favourite was doubtlessly the clarinet, which was still “young” at his time. Against the flute, he once famously wrote a rather unequivocal statement: “I soon got tired of writing for the same instrument (which I cannot bear)”. However, musicologists also know that Mozart’s jests need to be taken with a grain of salt; his music evidently demonstrates that he knew perfectly how to put the flute in the best light, and how to fittingly employ it. He might have been bored by the task of writing flute music, but he certainly did not consider the flute in the same negative way as the trumpet – that was an instrument he literally could not bear, to the point that it made him cry when he was a child.

That unsympathetic stance against the flute was jotted down by Mozart in his early twenties, when he was busy writing his four Flute Quartets. They had come to light following a commission he had earned while journeying through Germany and France; during that tour, he would eventually lose his mother. Flutist Johann Baptist Wendling knew a wealthy amateur flutist, Ferdinand Dejean, who commissioned Mozart to write a set of quartets for flute and strings. Mozart had business issues with Dejean, and it is possible that his alleged aversion to the flute had more to do with his aversion to the flutist who had commissioned these works (originally, the commission regarded “three small, light and short concertos and two quartets for the flute”). True, it took him more than the usual time to finish their composition, but the four Quartets which came out of his hands are among the finest examples of chamber music with flute ever written.

It was in those same years that Mozart made or renewed the acquaintance with the legendary musicians of the celebrated Mannheim orchestra, which had been moved to Munich following its aristocratic patron. It was probably the best orchestra in Europe at the time, and virtually all of its principal musicians were among the best soloists of their own instruments in activity in Mozart’s lifetime.

Already in 1777 in Mannheim, Mozart had got to know Christian Cannabich, the director of court music. Christian had a daughter, Rosa, who was a gifted and sensitive pianist, and to whom Mozart gave some piano lessons. For her, he wrote several pieces, claiming that they portrayed her personality and figure.

Indeed, Paul Badura Skoda observed that it is possible to sing the words “Rosa Cannabich” over the notes of the principal theme of the second movement of Piano Sonata KV 309; this may be intentional, indeed, since Mozart replaced the slow movement he had initially imagined with this one, stating that it mirrored his pupil’s character better. Allegedly, he had created – or at least sketched – the entire sonata during a coach ride.

This Sonata opens with a penetrating theme, played at the unison by both hands, and firmly establishing the Sonata’s key through a clear statement of the C-major triad. The second movement is the one conceived for, or almost “about” Rosa Cannabich, who, as Mozart wrote to his father, played it “with the utmost expression”. By way of contrast, the third movement was seen by Mozart himself as a boisterous piece, requiring a noteworthy degree of agility and virtuosity, but pervaded by a healthy amount of humour and irony.

In the same year, again in Mannheim, Mozart wrote Sonata KV 311, conceived, like its twin sister, for Rosa Cannabich (or perhaps for the daughters of Erasmus Franziskus Freysinger, who was a Counsellor at the Munich court). In both works we may observe a pedagogical intention, but, as happened with other genius musicians such as Bach, Schumann, or Bartók, the educational purpose is never at odds with musical beauty, elegance, and refinement.

The first movement is skillfully built, with the two themes seamlessly interlacing with each other and with accessory elements of musical composition, in a brilliant display of compositional technique. The reprise has a rather unusual form, since it begins by a restatement of the second theme (instead of the first) and has a brief recapitulation of the first theme in place of the coda.

The form of the second movement is likewise original, with a sort of hybridization between a varied theme and a rondo, whilst the third movement is a rondo proper, which, as was the case with KV 309, allows the young performer’s (or performers’) virtuosity to shine.

The dating of Sonata KV 331 has been recently revised. It had been long thought to have been written in Paris in 1778 (therefore shortly after the other two mentioned above), but careful study of the paper and calligraphy of the handwritten autograph manuscript led several scholars to postpone its composition to 1783, and therefore to the early Viennese years of the mature Mozart.

It is probably Mozart’s best-known Sonata, and deservedly so. Even though its extreme popularity is owed primarily to the Alla Turca movement which closes it, the extreme beauty of its first movement is among the unequalled masterpieces written by Mozart. It is an enchanting Theme with six Variations. The Theme is original by Mozart (even though it resembles a folksong he might have heard), and it displays an absolute purity of melodic lines and contrapuntal writing. Mozart frequently gave his best in the domain of the variations when he could use his own themes rather than those of popular songs or arias, and this is a clear demonstration of this reality. These variations are in fact among the most elegant, flowing, and expressive Mozart ever wrote, and are among the best examples of this genre in the history of music. Their degree of virtuosity increases progressively, up to the concluding Allegro which is brilliant and slightly tricky to perform.

It has been written that this Sonata resembles more closely a Suite than a Classical Sonata proper, and in fact its Siciliano-style first movement is followed by a Minuet with Trio, the latter characterized by hand-crossings similar to that of Variation IV of the first movement. The Sonata’s finale is the celebrated Alla Turca: a showpiece deliberately written with this purpose. Mozart had reckoned with the mode of the turqueries which were so popular at his time, and his Entführung aus dem Serail was a perfect example of that trend (but is not the only instance of exoticism in his music). Its overture, as Mozart himself described it to his father, was made of a sharp contrast between sections played pianissimo by the traditional Western orchestra of his time, and sections in forte with the participation of “Turkish” percussions and sounds. The same is observed here, with the “A” sections of this French Rondo played piano and an explosion of sound – skillfully written so as to exploit maximally the young fortepiano’s resources – in the refrains, played in robust octaves.

Again from the Viennese period, but already from Mozart’s very last years (1788) dates Sonata KV 533, which incorporates an earlier Rondo written in 1786, and probably intended as the third Rondo of a series of three (485 and 511). Although it was by no means exceptional for composers to “recycle” earlier works and insert them as part of new multi-movement pieces, in this case the seeming inconsistency in this Sonata’s genesis has led to its substantial neglect by many performers, and it is an unjustly forgotten masterpiece. Actually, Mozart’s compositional intent in putting together the new first movements and the “older” Rondo is clear, since he prepared this Sonata personally for publication. It was issued by Hoffmeister, one of Mozart’s publishers, who had some credit with Mozart: the composer paid him back with this beautiful piece, whose centrepiece is the enchanted Andante, in the sonata form, and with references to the compositional style of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

With the Oboe Quartet we are back to 1781, when Mozart had the opportunity of seeing again an old friend of him, the brilliant oboist Friedrich Ramm, who had been the first to hit the high F on his oboe. Mozart, always keen to appreciate the virtuosity of his colleagues and of the dedicatees of his music, employs this note frequently in this Quartet, which is written almost as an oboe concerto with chamber accompaniment. Its brilliancy and refinement seem to go beyond the borders of chamber music, and to aim for a true soloistic style.

All of these works were transcribed for flute and string trio by Franz Anton Hoffmeister, the publisher who has been cited in passing a few lines above. He was a composer himself, and perhaps he thought of himself as more of a musician than of a publisher, although the publishing company he founded was one of the leading enterprises in Vienna at his time, second only to Artaria. Hoffmeister befriended both Mozart and Beethoven (who called him “his brother”), and was perhaps more skilled as a talent-scout (securing the likes of these two musicians for his company) than as an entrepreneur in financial terms. In fact, after some years of successes, he sold his company to Kühnel and focused only on composition.

Since, as a composer, Hoffmeister was particularly celebrated for his flute works, these transcriptions are particularly careful and effective, and deserve to be played side by side with Mozart’s original flute quartets.

That unsympathetic stance against the flute was jotted down by Mozart in his early twenties, when he was busy writing his four Flute Quartets. They had come to light following a commission he had earned while journeying through Germany and France; during that tour, he would eventually lose his mother. Flutist Johann Baptist Wendling knew a wealthy amateur flutist, Ferdinand Dejean, who commissioned Mozart to write a set of quartets for flute and strings. Mozart had business issues with Dejean, and it is possible that his alleged aversion to the flute had more to do with his aversion to the flutist who had commissioned these works (originally, the commission regarded “three small, light and short concertos and two quartets for the flute”). True, it took him more than the usual time to finish their composition, but the four Quartets which came out of his hands are among the finest examples of chamber music with flute ever written.

It was in those same years that Mozart made or renewed the acquaintance with the legendary musicians of the celebrated Mannheim orchestra, which had been moved to Munich following its aristocratic patron. It was probably the best orchestra in Europe at the time, and virtually all of its principal musicians were among the best soloists of their own instruments in activity in Mozart’s lifetime.

Already in 1777 in Mannheim, Mozart had got to know Christian Cannabich, the director of court music. Christian had a daughter, Rosa, who was a gifted and sensitive pianist, and to whom Mozart gave some piano lessons. For her, he wrote several pieces, claiming that they portrayed her personality and figure.

Indeed, Paul Badura Skoda observed that it is possible to sing the words “Rosa Cannabich” over the notes of the principal theme of the second movement of Piano Sonata KV 309; this may be intentional, indeed, since Mozart replaced the slow movement he had initially imagined with this one, stating that it mirrored his pupil’s character better. Allegedly, he had created – or at least sketched – the entire sonata during a coach ride.

This Sonata opens with a penetrating theme, played at the unison by both hands, and firmly establishing the Sonata’s key through a clear statement of the C-major triad. The second movement is the one conceived for, or almost “about” Rosa Cannabich, who, as Mozart wrote to his father, played it “with the utmost expression”. By way of contrast, the third movement was seen by Mozart himself as a boisterous piece, requiring a noteworthy degree of agility and virtuosity, but pervaded by a healthy amount of humour and irony.

In the same year, again in Mannheim, Mozart wrote Sonata KV 311, conceived, like its twin sister, for Rosa Cannabich (or perhaps for the daughters of Erasmus Franziskus Freysinger, who was a Counsellor at the Munich court). In both works we may observe a pedagogical intention, but, as happened with other genius musicians such as Bach, Schumann, or Bartók, the educational purpose is never at odds with musical beauty, elegance, and refinement.

The first movement is skillfully built, with the two themes seamlessly interlacing with each other and with accessory elements of musical composition, in a brilliant display of compositional technique. The reprise has a rather unusual form, since it begins by a restatement of the second theme (instead of the first) and has a brief recapitulation of the first theme in place of the coda.

The form of the second movement is likewise original, with a sort of hybridization between a varied theme and a rondo, whilst the third movement is a rondo proper, which, as was the case with KV 309, allows the young performer’s (or performers’) virtuosity to shine.

The dating of Sonata KV 331 has been recently revised. It had been long thought to have been written in Paris in 1778 (therefore shortly after the other two mentioned above), but careful study of the paper and calligraphy of the handwritten autograph manuscript led several scholars to postpone its composition to 1783, and therefore to the early Viennese years of the mature Mozart.

It is probably Mozart’s best-known Sonata, and deservedly so. Even though its extreme popularity is owed primarily to the Alla Turca movement which closes it, the extreme beauty of its first movement is among the unequalled masterpieces written by Mozart. It is an enchanting Theme with six Variations. The Theme is original by Mozart (even though it resembles a folksong he might have heard), and it displays an absolute purity of melodic lines and contrapuntal writing. Mozart frequently gave his best in the domain of the variations when he could use his own themes rather than those of popular songs or arias, and this is a clear demonstration of this reality. These variations are in fact among the most elegant, flowing, and expressive Mozart ever wrote, and are among the best examples of this genre in the history of music. Their degree of virtuosity increases progressively, up to the concluding Allegro which is brilliant and slightly tricky to perform.

It has been written that this Sonata resembles more closely a Suite than a Classical Sonata proper, and in fact its Siciliano-style first movement is followed by a Minuet with Trio, the latter characterized by hand-crossings similar to that of Variation IV of the first movement. The Sonata’s finale is the celebrated Alla Turca: a showpiece deliberately written with this purpose. Mozart had reckoned with the mode of the turqueries which were so popular at his time, and his Entführung aus dem Serail was a perfect example of that trend (but is not the only instance of exoticism in his music). Its overture, as Mozart himself described it to his father, was made of a sharp contrast between sections played pianissimo by the traditional Western orchestra of his time, and sections in forte with the participation of “Turkish” percussions and sounds. The same is observed here, with the “A” sections of this French Rondo played piano and an explosion of sound – skillfully written so as to exploit maximally the young fortepiano’s resources – in the refrains, played in robust octaves.

Again from the Viennese period, but already from Mozart’s very last years (1788) dates Sonata KV 533, which incorporates an earlier Rondo written in 1786, and probably intended as the third Rondo of a series of three (485 and 511). Although it was by no means exceptional for composers to “recycle” earlier works and insert them as part of new multi-movement pieces, in this case the seeming inconsistency in this Sonata’s genesis has led to its substantial neglect by many performers, and it is an unjustly forgotten masterpiece. Actually, Mozart’s compositional intent in putting together the new first movements and the “older” Rondo is clear, since he prepared this Sonata personally for publication. It was issued by Hoffmeister, one of Mozart’s publishers, who had some credit with Mozart: the composer paid him back with this beautiful piece, whose centrepiece is the enchanted Andante, in the sonata form, and with references to the compositional style of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

With the Oboe Quartet we are back to 1781, when Mozart had the opportunity of seeing again an old friend of him, the brilliant oboist Friedrich Ramm, who had been the first to hit the high F on his oboe. Mozart, always keen to appreciate the virtuosity of his colleagues and of the dedicatees of his music, employs this note frequently in this Quartet, which is written almost as an oboe concerto with chamber accompaniment. Its brilliancy and refinement seem to go beyond the borders of chamber music, and to aim for a true soloistic style.

All of these works were transcribed for flute and string trio by Franz Anton Hoffmeister, the publisher who has been cited in passing a few lines above. He was a composer himself, and perhaps he thought of himself as more of a musician than of a publisher, although the publishing company he founded was one of the leading enterprises in Vienna at his time, second only to Artaria. Hoffmeister befriended both Mozart and Beethoven (who called him “his brother”), and was perhaps more skilled as a talent-scout (securing the likes of these two musicians for his company) than as an entrepreneur in financial terms. In fact, after some years of successes, he sold his company to Kühnel and focused only on composition.

Since, as a composer, Hoffmeister was particularly celebrated for his flute works, these transcriptions are particularly careful and effective, and deserve to be played side by side with Mozart’s original flute quartets.