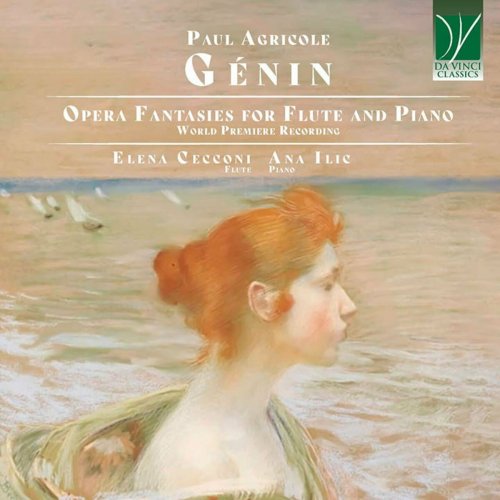

01. Fantaisie sur "La Traviata", Op. 18

02. 6 Fantaisies progressives sur des Motif Favoris, Op. 12: IV. Così fan tutte

03. 6 Fantaisies progressives sur des Motif Favoris, Op. 12: V. La Cenerentola

04. 6 Fantaisies progressives sur des Motif Favoris, Op. 12: VI. Melodies

05. Fantaisie sur "La Colombe" de Gounod

06. Fantaisie sur "Rigoletto", Op. 19

The virtuosity of the nineteenth century’s instrumental repertoire was significantly shaped by musicians, composers, and performers who developed an idiomatic language for their instruments, elevating music to new heights of complexity and demanding greater technical skill. The flute, in particular, underwent a period of substantial development and innovation during this time. Many flautists and makers contributed to refining its mechanics, notably due to the work of Theobald Böhm, who presented his instrument at the Académie des Sciences in Paris in 1832. In France, enhancements in sound quality and greater agility and precision in playing allowed the flute to become a leading instrument in concert halls and the drawing rooms of the upper bourgeoisie.

The popular operatic repertoire served as a privileged source of inspiration for creative instrumental reinterpretations. The flute proved to be an excellent medium, offering broad capabilities for emulating the timbre, agility, dynamics, and emotional nuances of the human voice. Moving away from the traditional variation form, which started from a well-known motif or an aria’s opening, the most famous operatic themes were reworked and revisited to create original pieces. These pieces, through instrumental transposition of an entire episode or often of various moments, provided listeners with a sort of synthesis of the melodrama that inspired them. Thus, the performer’s task was not merely to recall and rework main themes, but to express the opera’s atmosphere, offering a new and personal interpretation.

The cultural and social significance of the proliferation of ‘paraphrases’, ‘fantasies’, and ‘reminiscences from’ operas, coupled with the rich music publishing industry that disseminated popular arias with piano accompaniment, was extraordinarily important for spreading the operatic repertoire. Hence, melodrama extended beyond the stage’s confines to reach a wider audience.

Paul-Agricole Génin (Avignon, 14/2/1832 – Paris, 22/12/1903), trained at the Paris Conservatory under Louis Dorus, one of the first flautists to use Böhm’s flute in France. Largely overlooked in major biographical repertoires, scant but essential information reveals his long professional career and considerable compositional output. The 1900 volume, “Le Conservatoire National de Musique et de Déclamation: documents historiques et administratifs,” records the Conservatory’s annual competition results. In 1860, the first prize for flute was awarded to Paul Taffanel, author of the flute method, and the second to Paul-Agricole Génin, who won the first prize the following year. By 1875, he was the principal flautist of the Orchestre Colonne, then at the Théâtre des Italiens, La Comédie Française, the Casino de Vichy, and the Concerts du Chatelet.

He also focused on flute technique, authoring “Tablature du doigté général de la flûte Boehm cylindrique,” published in 1858 by Clair Godfroy ainé. His compositional corpus includes over 66 operatic works for flute and saxophone, which enjoyed significant publishing success with leading French publishers of the time. His only composition that has not fallen into obscurity is op. 14, based on Paganini’s “Il Carnevale di Venezia,” a brilliant fantasy with variations for flute and orchestra published in 1872. Remaining in the repertoire due to the technical demands it places, it represents a challenge for flautists wishing to showcase their skills. The piece, from its first recording for the Gramophone label in 1927 with flautist Marcel Moyse (1889-1984), continues to enjoy moderate publishing and recording success today.

Many of Paul-Agricole Génin’s works for flute and piano are primarily inspired by the world of melodrama. Giuseppe Verdi, who may have met Génin during his stays in Paris between 1847 and 1894, was inevitably one of the main references. His fantasies on “Un ballo in maschera” (op. 17, 1879), “Traviata” (op. 18, 1879), “Rigoletto” (op.19, 1879), and “Souvenir d’Aïda” (op. 31, 1880) remain. The fantasies on “Traviata” and “Rigoletto,” featured on this CD, are built on a continuous dialogue between the flute and piano, where themes and variations are adapted to the different peculiarities of the two instruments. The flute is entrusted with increasingly rich and complex variations that require great agility, creating highly effective sound plays.

The famous motifs of Verdi’s operas, sometimes clearly recognizable or elaborately varied and ornamented from their first exposition, are presented in an order that does not always follow their succession in the opera. The atmosphere of “Traviata” is expressed by the famous motif “Libiam ne’ lieti calici,” which opens the piece introduced by the piano alone and immediately taken up by the flute with variations that enrich its melodic progression. The theme, expressed by pure citation or by refined variation plays, frames the piece ensuring its formal cohesion. In a dense sonic texture, the turmoil of Violetta is expressed in episodes built on the protagonist’s most expressive arias, such as “Gran Dio! Morir sì giovane” and “Addio del passato.”

In the fantasy on “Rigoletto,” Gilda’s aria “Caro nome” opens the composition with a dense interweaving of variations and frames the episode based on the poignant themes of the duet between Rigoletto and Gilda “Deh non parlare al misero,” followed by the somber response “Quanto dolor.” The return of the “Caro nome” theme offers a path rich in broad variations played on the flute’s agility, constructing sonic arabesques. The piece finally concludes with a significant episode built on the variations of the Duke’s aria “La donna è mobile.”

Following the publishing tradition of the time, Génin published various collections that included fantasies on famous motifs. Examples include “Six Fantaisies progressives sur des Motifs Favoris op. 12,” published around 1872 in the fourth series of the collection L’attrait du flûtiste by publisher Girod. The fantasies revisit the “motifs favoris” of “La Vestale” by Saverio Mercadante, “Sardanapale” by Victorin de Joncières, “La Straniera” by Vincenzo Bellini, “Così fan tutte” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “La Cenerentola” by Gioachino Rossini, and a tribute to Franz Schubert, the only piece not linked to the operatic world. Génin constructs his fantasy on the expressive melody of Schubert’s serenade “Ständchen D957” from the cycle Schwanengesang, followed by the poignant lied “Abschied von einem Freunde D586.”

The fantasy on “Così fan tutte” opens with two arias of Ferrando presented in reverse order compared to the original score: the passionate aria “Ah, lo veggio” is followed by the cantabile “Un’aura amorosa.” By contrast, the livelier conclusion is based on Dorabella’s aria “È amore un ladroncello.”

In revisiting “La Cenerentola,” Paul-Agricole Génin first focuses on the character of Don Ramiro who, abandoning his disguise as a squire, sings the aria “Sì, ritrovarla io giuro,” followed by the slower movement “Pegno adorato e caro.” The fantasy concludes with Cinderella’s redemption with the rondo “Nacqui all’affanno” and the finale “Non più mesta.”

The overview of Génin’s work cannot exclude a tribute to French musical theatre, to which a large number of his compositions are inspired. In the collection “Les succès contemporains, nouvelle collection de Fantaisies sur des opéras modernes pour flûte et piano” issued by publisher Choudens, fantasies are gathered on famous motifs from French operas, such as “Faust,” “Mireille,” “Roméo et Juliette,” “Philémon et Baucis,” “La colombe,” “Sapho,” and “Le soir” by Charles Gounod; “Carmen,” “L’Arlesienne,” and “La jolie fille de Perth” by Georges Bizet; “La mascotte,” “La cigale et la fourmie,” “Le gran Mogol,” and “Gillette de Narbonne” by Edmond Audran; “Rip” by Robert Planquette; “La fille du Tambour-major” and “La jolie parfumeuse” by Jacques Offenbach; and “Les Mousquetaires au Convent” by Louis Varney.

The fantasy on Charles Gounod’s “La Colombe” draws inspiration from the opéra comique, which, following its initial Parisian premiere in 1866, remained a staple on European stages for several years. Igor Stravinsky, in his “Chroniques de ma vie,” described the opera as “brief, yet delightful,” referencing a Diaghilev project that oversaw the production of the opera in Monte Carlo in 1924. Génin’s fantasy, published in 1892, is linked to the opera’s early success. The piece is structured around various episodes, including the Entr’act from the second act, Sylvie’s entrance aria “Si, je suis belle encore,” her romance “Que de rêves charmants emportés sans retour,” and finally, Maître Jean’s ariette “Les amoureux c’est la mode.” Once again, the fantasy serves as a crucial testament in preserving the memory of operas that are now seldom staged.

![Genre - Commercial Success (2026) [Hi-Res] Genre - Commercial Success (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1768906441_j1odg2907l945_600.jpg)