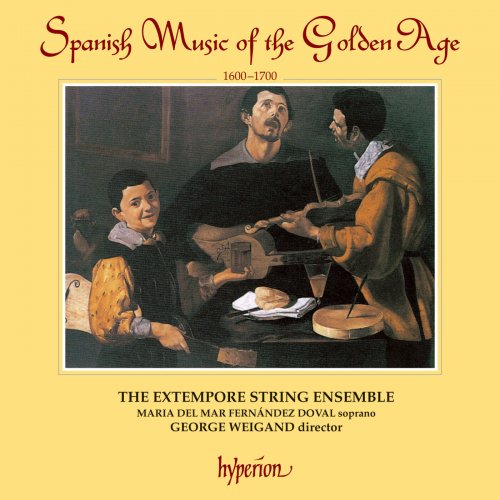

The Extempore String Ensemble, George Weigand - Spanish Music of the Golden Age, 1600-1700 (1989)

Artist: The Extempore String Ensemble, George Weigand

Title: Spanish Music of the Golden Age, 1600-1700

Year Of Release: 1989

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:04:49

Total Size: 327 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Spanish Music of the Golden Age, 1600-1700

Year Of Release: 1989

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:04:49

Total Size: 327 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Rujero – Paradetas – Folias – Pabana – Vacas

02. Pasacalle – Desengañemonos ya

03. Pasacalle – Filis No cantes

04. Zarabanda – Marizapalos – Tarentela

05. Pasacalle – Aquella sierra nevada

06. Hachas – Folias – El Villano – Matachin

07. Pasacalle – Menguilla, yo me muriera

08. Granduque – Canarios

09. Galeria de Amor – Vuelta – Zarabanda – Españoleta – Chacona

10. Pasacalle – Sin duda piensa Menguilla – No piense Menguilla ya

During the later sixteenth and throughout the seventeenth centuries – Spain’s Golden Age – Spanish music developed its individual character to a high degree. The combination of vibrant rhythms partly derived from folk music, use of glosas and diferencias (extemporised divisions and variations) over ground bass, dance and vocal music, and an adventurous and inventive sense of harmony characterise this repertoire.

Whilst Spain was to a large extent voluntarily isolated from many of the cultural trends fashionable in the rest of Europe, notably French style, there had been for some time a degree of cultural exchange with Italy. This is not surprising since much of Italy was part of the Spanish Empire. Given Italy’s cultural pre-eminence in the Renaissance, it might be assumed that musical influences generally flowed from Italy to Spain. This, however, was far from the case. This impression is caused partly by the amount of music published in Italy compared with the relatively small amount published in Spain. Italy had, for a long time, both a thriving printing industry and sources of good-quality paper. As a result, many Spanish authors and composers had their works printed in Italian cities like Naples, Rome and others either with links to the Spanish crown or directly under its control, taking advantage of the existing facilities and sometimes printing their works in both Spanish and Italian.

It was in Spain that a great many of the instruments in use throughout Europe were developed. The system of tablature, used universally to notate music for stringed instruments in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, was adapted from the Moorish system of using letters to indicate intervals on the fingerboard of an instrument. In the Middle Ages Spanish treatises on music theory were used by subsequent theorists of other nations. Spain exported a wealth of musical forms including the pasacalle, zarabanda, chacona, españoleta, canarios and brando to Italy and subsequently to the rest of Europe.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713) brought chaos and divided loyalties and ended with a French Bourbon monarch on the Spanish throne. The French influence would now make itself felt at the court in Madrid, but by this time nearly all the great lights were dead or in exile and the Golden Age had come to an end.

The music on this recording comprises instrumental music and songs which would have been heard in the royal zarzuelas, at the public theatres of Madrid and Seville, and for saraos or social dances at noble households during the seventeenth century.

The zarzuela at this time was an elaborate stage entertainment which often took its subject matter from classical mythology. It combined music, dance and drama rather like the masque in England, and was named for the royal villa where it was first performed. Zarzuelas were more popular than operas in Spain, probably because the Spanish preferred spoken drama to long passages of recitative between arias. Zarzuelas drew upon the nation’s greatest composers and poets, notably the playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681). Music was composed by royal musicians including the harpist Juan Hidalgo (1614-1685), Juan de Celis (died 1695) and the notorious tenor/priest/highwayman/murderer Jose Marín (1619-1699). Unusually for the time, Marín wrote both music and lyrics for his songs. By coincidence, one of Marín’s outlaw band was a fellow priest and poet, Juan Bautista Diamante (1625-after 1674). Diamante (who incidentally was credited with even more murders than Marín), like Calderón, collaborated with Juan Hidalgo for zarzuelas.

The same actors and actresses often took part in both zarzuelas and comedias (plays). There are contemporary accounts of performances of comedias being cancelled because part of the cast had been called, by royal command, to rehearse or perform a zarzuela. Music played a very important part in the comedias given in the many theatres throughout Spain. Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616), Lope de Vega (1562-1635), Tirso de Molina (1583-1648) and Calderón all featured music and dance prominently in their works. They also wrote short, music-based entertainments to be performed on stage as an integral part of the comedia. These comprised: loas (prologues), entremeses and saynetes (one-act interludes or farces between the acts of the comedia), mogingangas (popular masques) and jacaras (ballad interludes sometimes even sung from horseback!). The comedia usually concluded with a sung set dance finale or bayle.

The first Suite consists of some of the most popular grounds for variations and dances, most of which had survived from the sixteenth century and remained popular into the eighteenth. The Rujero is probably named from a character in the epic ballad ‘The Song of Roland’ which existed in Spanish versions from at least the thirteenth century. The piece was also well known in Italy and England. The Paradetas dates from the second half of the seventeenth century and is a set dance for a couple. The Folias was originally Portuguese but early on became a characteristically Spanish form. It was at first very fast (the name means ‘mad dance’). The Pabana (pavan), one of the best known court dances of the Renaissance, was probably another native Spanish form. It remained popular in Spain and still exists in some parts of the country. Vacas is a ground bass which is a survival of the older song ‘Guardame las vacas’, used as the basis for sets of variations for vihuela, harp, guitar and other instruments.

Among the most common dances for the theatre were: the zarabanda, marizapalos, tarentela, hachas, folias, villano, matachin and chacona. Both the zarabanda and chacona were reputed to have been originally Indian dances brought back to Spain from the New World. Fray Diego Duran, a priest from Seville living in Mexico, wrote in 1579 about a lascivious Indian dance, the cuecueheuycatl which he thought very similar to ‘that zarabanda danced by our naturales’ (creoles of Spanish descent born in Mexico). Cervantes, who used zarabandas and other dances in his plays, suggests, however, that it was invented in Hell. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries it was a light, quick dance which was banned by edict several times for being indecent. Despite this prohibition, reinforced by the threat of whipping or a term in the galleys, the dance remained popular and was joined by others even more scandalous. Not all churchmen, however, were opposed to popular dances; as the zarabanda and others were danced at the Feast of Corpus Christi in Seville and even in cathedrals by clergy in the normal practice of singing and dancing processionals for the mass. In fact, many composers of dance and theatre music were clerics. The marizapalos may have come from the marionette theatre popular at the time (and in Sicily is still presenting traditional plays based on mythology and legend, such as the battles between Christians and Moors). The tarentela was imported from Spain’s provinces in southern Italy and was traditionally accompanied by the dancer’s tambourine. The hachas was a torch dance, described in a loa of 1636:

Enter the whole company two by two with hands joined, dancing to the sound of instruments and bearing torches; making a reverence, they sing.

The villano was a solo dance for a man in the character of a villano or rustic. Holding his sombrero (wide-brimmed hat) in both hands, he would execute a series of spectacular high kicks, leaps and mid-air spins. Matachines were comedia characters – one of several clown stereotypes well known throughout Europe. The theatre dance was often performed with the matachines capering in outlandish costumes.

The granduque and galeria de amor are of Italian origin but remained popular in Spain long after passing out of fashion in Italy. The granduque was a set dance which became a ground for diferencias in the seventeenth century. The canarios was another ‘ethnic’ dance intended to represent the ‘shuffling’ dances of the Canary Islanders. The vuelta is an integral part of the galeria de amor and is a triple-time version serving the same function as a galliard to a pavan in England.

By the later seventeenth century the zarabanda, chacona and folia had become slower, more graceful and less energetic than earlier versions and the chacona had overtaken the zarabanda as the most popular dance in Spain. According to Lope de Vega and other writers the chacona had come from the Indies or Tampico on the East coast of Mexico.

Pasacalles, the short instrumental preludes to the songs on this recording, are pieces which were originally intended to serve as promenading or serenading music to accompany singers onto the stage. Pasacalles were associated with plucked instruments as these could be played whilst strolling; either purely instrumentally or while singing too. They were usually extemporised pieces based upon the tonality of the song to follow. In keeping with this practice several of the pasacalles in the programme are completely extemporised from only a very simple bass line.

The songs by Jose Marín, Juan Hidalgo and Juan de Celis demonstrate the wide range of expressiveness from the sadness of disillusioned love in Desengañemonos ya to the metaphorical irony of Filis no cantes to the reflective introspection of Aquella sierra nevada. The three songs about the character Menguilla present three different musical moods and three different emotional reactions to Menguilla’s cruelty in matters of love. In Menguilla, yo me muriera the lover wishes to be put out of his misery but is at the same time afraid that his life will be empty. In Sin duda piensa Menguilla the lover laments his predicament wherein Menguilla loves lightly and in an estribillo laden with multiple meanings; the more he doesn’t like it/is unable to love/can’t stand more, the more she likes it/more she wants/more she loves. The lover in No piense Menguilla ya foreswears love but probably will remain a fool as he fancies himself as irresistible and puts his rejection by the girl solely down to her lack of taste in men.

The manuscript from which the songs come contains instructions to play a pasacalle in the appropriate tonality before each song. No music for these pasacalles is given in the manuscript. This indicates that the collection is of stage songs; probably for zarzuelas. This is further borne out by many of the lyrics which contain allusions to classical mythology, many double and triple levels of meaning (often difficult to convey adequately in English) and the fact that the composers were in the Royal service.

The use of spontaneous extemporisation was an essential part of performance in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It manifests itself here in a number of different ways besides ornamentation and realisation of continuo from a figured bass. Additional lines (discantamientos) are improvised, tunes and composed lines are developed by extemporised divisions and variations (glosas and diferencias), and melodies are invented (salteadas melodias) over a ground bass or harmonic pattern. The extent of this spontaneity is perhaps most noticeable in solo variations and in the dialogues and duels between two instruments extemporising simultaneously. These forms are used extensively and in various combinations on this recording.

The music for the programme has been drawn from a variety of sources, notably collections for guitar, harp, keyboard and viol including those by Gaspar Sanz (Zaragoza, 1674 and 1679), Lucas Ruiz de Ribayaz (Madrid, 1677) and Francisco Guerau (Madrid, 1684). For while there is little available Spanish music in parts for instrumental ensembles from this period, these tutors and collections for solo instruments indicate what the favoured repertoire was from the frequency with which certain pieces recur. The books also give, in many cases, sets of variations suggesting the style of treatment for performance. Also of use in deciding matters of style and tempi are the dancing tutors such as those by Juan de Esquivel (1642) and Juan Antonio Jaques (c1680). Esquivel also provides insight into the instrumental side of dance practice by, among other things, indicating the correct way to hold the guitar while playing and dancing simultaneously, numerous references to the sound and playing style of various stringed instruments, and praise for one famous bandurria player both as an instrumentalist and dance musician.

The songs all come from a manuscript, circa 1690, containing songs for solo voice with guitar accompaniment, mostly by Jose Marín and now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

![The Voros Collective - Intercontinental Man (2026) [Hi-Res] The Voros Collective - Intercontinental Man (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772344932_cover.jpg)

![Ying-Da Chen - Animal Triste (2026) [Hi-Res] Ying-Da Chen - Animal Triste (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772673724_eioi3gteovgg7_600.jpg)

![Clifford Brown - Oldies Mix: Brownie (Remastered) (2025) [Hi-Res] Clifford Brown - Oldies Mix: Brownie (Remastered) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/03/2kclmln8ho6kq4e7w6k0ouqcm.jpg)