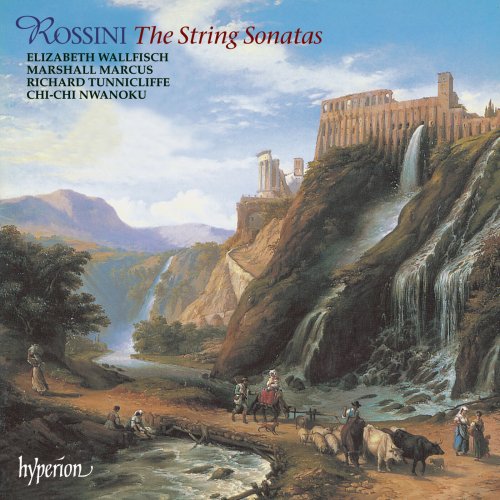

Elizabeth Wallfisch, Richard Tunnicliffe, Chi-Chi Nwanoku, Marcus Marshall - Rossini: The 6 String Sonatas (1992)

Artist: Elizabeth Wallfisch, Richard Tunnicliffe, Chi-Chi Nwanoku, Marcus Marshall

Title: Rossini: The 6 String Sonatas

Year Of Release: 1992

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:19:38

Total Size: 365 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Rossini: The 6 String Sonatas

Year Of Release: 1992

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:19:38

Total Size: 365 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. String Sonata No. 1 in G Major: I. Moderato

02. String Sonata No. 1 in G Major: II. Andante

03. String Sonata No. 1 in G Major: III. Allegro

04. String Sonata No. 2 in A Major: I. Allegro

05. String Sonata No. 2 in A Major: II. Andante

06. String Sonata No. 2 in A Major: III. Allegro

07. String Sonata No. 3 in C Major: I. Allegro

08. String Sonata No. 3 in C Major: II. Andante

09. String Sonata No. 3 in C Major: III. Moderato

10. String Sonata No. 4 in B-Flat Major: I. Allegro vivace

11. String Sonata No. 4 in B-Flat Major: II. Andante

12. String Sonata No. 4 in B-Flat Major: III. Allegretto

13. String Sonata No. 5 in E-Flat Major: I. Allegro vivace

14. String Sonata No. 5 in E-Flat Major: II. Andante

15. String Sonata No. 5 in E-Flat Major: III. Allegretto

16. String Sonata No. 6 in D Major: I. Allegro spiritoso

17. String Sonata No. 6 in D Major: II. Andante assai

18. String Sonata No. 6 in D Major: III. Allegro. Tempesta

Rossini’s six string sonatas were written in Ravenna during the summer of 1804. The composer was just twelve years old and staying at the home of amateur double bass enthusiast Agostini Triossi – hence the prominent role that instrument assumes. At first these youthful works were scored for two violins, violoncello and double bass only. They were most likely categorized as ‘sonate a quattro’, for Rossini’s score clearly labels each instrument in the singular. Today’s performances are most commonly presented by ensemble groups. Each violin line is typically carried by three performers, the cello ‘voice’ is duplicated and a single bass completes the ensemble. For this recording we finally return to Rossini’s original, neglected, four-instrument configuration.

The existence of these early sonatas was well documented from the outset, though for many years their whereabouts remained a mystery. Most scholars assumed they had long since been destroyed. But in 1954 Rossini’s original version turned up at the Library of Congress, Washington. It was prefaced by A Bonaccorsi and corresponded with an earlier 1942 discovery of five of the works (No 3 was absent) scored as standard string quartets and first published in Milan in 1826 by Ricordi. Alfredo Casella edited this wartime discovery for publication in 1951. Today, however, the conventional quartet scoring and a further transposition for winds (flute, clarinet, bassoon and horn) dated 1828/1829 are together widely regarded as less than wholly authentic. Both adaptations seem likely to be the work of long-forgotten transcribers.

Today’s musicologists are quick to point out deficiencies and weaknesses in the original works. While doing so they evidently lose sight of two remarkable facts: Rossini was not yet a teenager when they were written. Even more, he had scarcely begun concentrated musical studies. The extent to which he was already familiar with the music of Haydn and Mozart is open to conjecture. It could hardly have been more than a limited acquaintance, though in later life he referred to the latter composer as ‘the admiration of my youth, the desperation of my mature years, the consolation of my old age’. Whatever Rossini’s earliest influences, few would dispute that, as a twelve-year-old, Mozart produced nothing of greater stature. Mendelssohn reached fourteen before he completed the agreeable twelve String Symphonies and it was not until well into adolesence, aged sixteen or so, that he completed the Octet and Midsummer Night’s Dream overture, works so often upheld as examples of surpassing early maturity.

Rossini’s six sonatas did not exemplify that same advanced degree of inwardness and precocity. How indeed could he have reached such at point? He had barely begun instruction in composition and the works were written just two years after a desperate search for sufficient work forced his parents to leave Pesaro, the composer’s Adriatic birthplace. For ten childhood years his father, horn player Giuseppe Rossini, found occasional jobs and held posts as town trumpeter and an inspector of slaughterhouses. The youngster was cared for by his maternal grandmother while both parents were bound to tour as work became available. Eventually prospects in Bologna seemed more promising and in 1802 the family finally moved. Guiseppe entered the Bologna Accademia Filarmonica and Gioacchino’s mother, a minor opera star, retired with a throat ailment. Now their son attended private music instruction with Angelo Tesei. He played the harpsichord, sang at a nearby church and in 1805 appeared as the boy Adolfo in Paer’s Camilla, a production at the Teatro del Corso. But it wasn’t until 1806, his fourteenth year, that Rossini was permitted to join his father in the Accademia Filarmonica. By this time he had begun counterpoint studies with Padre Stanislao Mattei. Four more years were to elapse before his 1810 opera debut with a one-act comedy, La Cambiale di Matrimonio, at the Teatro San Moìse Theatre in Venice. This production set him firmly on the path to thirty-nine entertaining operas, the Stabat mater and his large-scale Petite Messe Solennelle, the body of work on which Rossini’s creative reputation largely depends. The string sonatas, completed six years earlier, were clearly a prodigious accomplishment. They are Rossini’s earliest recognized compositions with the sole exception of a single, negligible song. All six works display his clear and instant appeal, revealing a child of manifest talent; already the author of his own acclaimed destiny as both man and musician. The disparate elements of a fully developed musical genius can be detected within these genial scores.

Each of Rossini’s six spirited sonatas is in a major key and follows a conventional three-movement ‘quick–slow–quick’ pattern. Their opening movements take up half or more of each sonata’s total duration. Yet they display little of the formal development so characteristic in the Classically-structured work of composers to the north, Mozart and Beethoven in particular. Instead Rossini’s initial material recurs in parallel, contrasted, or tranposed form, always imbued with communicative vitality. Three of the central Andantes adopt minor keys and at times their overriding melodic charm conceals, however briefly, a somewhat deeper note than most commentators are prepared to ascribe to so young a composer. The Andante from Sonata No 2 in A major is a case in point. Four of his the finales are designated Presto. By comparison the third sonata culminates in a movement marked Moderato. Here Rossini’s instructive title misleadingly conceals a basic yet dazzlingly headlong set of variations with the double bass taking a brief, one-off spotlight. Sonata No 6 in D major concludes with a finale titled ‘Tempesta’, looking forward a quarter of a century to the storm of William Tell.

Together these six works demonstrate the astonishing speed with which Rossini was developing. At this tender age he clearly chose to depart from prevailing musical expectations. He shrewdly separates the roles of cello and bass, allowing both instruments their share of the limelight. Equally, neither of the two violin lines is subservient and each treble ‘voice’ has been permitted its own ascendancy as the works unfold. Already there is evidence of the bel canto design that Rossini advanced and developed beyond its earlier formalism. He relied heavily on the device of cavatina and cabaletta; the former required singers to sustain a line with beauty of tone, nuance and colour, while the cabaletta called for a high degree of virtuosity.

The sonatas embody the immediacy and fluency that Rossini’s operas never relinquish. At the same time they glance back to Classical models of an immediately preceding generation; techniques common in the music of Simon Mayr, Pietro Carlo, Valentino Fioravanti and Ferdinand Paer. An understandable naivety of expression almost certainly stems from childhood uncertainties. In his later operas Rossini finally shifted from the eighteenth-century buffo tradition to more forward-looking opera seria forms. But the keys to that change were always present in his music. Just as surely these childhood offerings bear tell-tale, albeit embryonic marks of their creator’s adult traits. They tell of a style that would lead to Epicurean pursuits, a humour that gave rise to mischievous, sometimes cutting bons mots, and an expressive demeanour essential for a ‘grand seigneur’ of the musical establishment.

As sparkling, melodic, instantly appealing concert entertainment the effect of Rossini’s six string sonatas is never in question – all six works call for an ensemble of striking finesse, beauty, accuracy and outright virtuosity. Later in life their composer reportedly bragged: ‘Give me a grocery list and I’ll set it to music.’ With this, his first musical shopping spree, the outcome proved miraculous; a confectionary bon-bon in glittering wrapping.