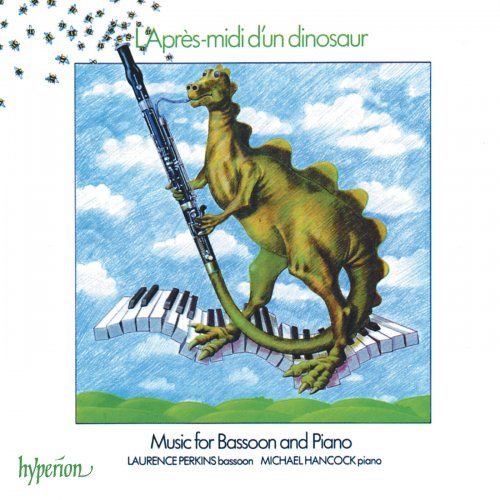

Laurence Perkins, Michael Hancock - L'après-midi d'un dinosaur: Music for Bassoon & Piano (1989)

Artist: Laurence Perkins, Michael Hancock

Title: L'après-midi d'un dinosaur: Music for Bassoon & Piano

Year Of Release: 1989

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:53:50

Total Size: 181 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: L'après-midi d'un dinosaur: Music for Bassoon & Piano

Year Of Release: 1989

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:53:50

Total Size: 181 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Bassoon Sonata in F Major: I. Vivace

02. Bassoon Sonata in F Major: II. Ballade. Moderato, ma sempre a piacere

03. Bassoon Sonata in F Major: III. Allegretto

04. Bassoon Sonata in F Major: IV. Moderato – Vivace

05. Romance, Op. 62

06. 4 Sketches: I. A Peaceful Piece

07. 4 Sketches: II. A Little Waltz

08. 4 Sketches: III. L'après-midi d'un dinosaur

09. 4 Sketches: IV. Polka

10. Marche funèbre d'une marionnette, CG 583

11. Carignane

12. Solo de concert, Op. 35

13. Allegro spiritoso (Arr. Perkins)

14. Bassoon Sonata in G Major, Op. 168: I. Allegretto moderato

15. Bassoon Sonata in G Major, Op. 168: II. Allegro scherzando

16. Bassoon Sonata in G Major, Op. 168: III. Molto adagio – Allegro moderato

The bassoon has never been regarded as very much more than the bass instrument of the orchestral woodwind section, important and rewarding though that role often is. Most music lovers are vaguely familiar with the Mozart Concerto, a handful with the Weber Concerto, and just about everyone with the 'Allegro spiritoso' (which isn't an original bassoon piece anyway!) and that's as far as it goes. Concert promoters are often wary of featuring a solo bassoon in their programmes ("Will people really turn out for this?") and the consequence of all this is that the attractive repertoire of music for solo bassoon is virtually unknown. Yet, modest in extent though this repertoire is, it nevertheless includes works by such composers as Telemann, Vivaldi, J C Bach, Mozart, Weber, Hindemith and Villa-Lobos (to name but a few other than those on this record), all of which are worthy of many more airings than they receive.

This record contains some of the finest works from the bassoon's recital repertoire, and their contrasting moods and styles demonstrate the very wide range of the instrument, from the exotic lyricism of Ibert's Carignane to the wistful melancholy of Elgar's Romance, both sharply contrasted by the restless, impassioned mood of Pierné's Solo de Concert. There are touches of gentle humour, too, in Gordon Jacob's Four Sketches and Gounod's Funeral March of a Marionette. There is no doubt that the bassoon's principal role will be forever as a member of a symphony orchestra, but hopefully this record will not only introduce music lovers to some attractive and unjustly neglected pieces, but will also demonstrate the bassoon's capabilities as a lyrical, expressive and versatile solo instrument.

The story of William Martin Yeates Hurlstone is rather sad. Born in London in 1876, he was something of a musical child prodigy and, at the age of eighteen, he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music to study composition with Stanford. He was also a brilliant pianist and appeared as soloist in his own Piano Concerto at St James's Hall in 1896. He was appointed Professor of Counterpoint at the Royal College, but it was a post that he was not able to hold for long for he suffered from acute bronchial asthma and died in London in 1906, aged just thirty. Nevertheless, he left us with a legacy of fine compositions including a considerable quantity of Chamber music. Unfortunately, Hurlstone's music has received scant attention over the years, not least his Sonata for bassoon and piano (here receiving its first commercial recording) which was out of print for a long time until Emerson Edition had the enterprise to reprint is recently. Originally published in 1904, it was dedicated to a well-known bassoonist of the time, Edward Dubrucq.

As one might expect, the piano part in this Sonata is substantial. But the same can also be said of the bassoon part—not particularly in terms of virtuoso writing but more in the exploration of the bassoon's expressive range. A cheerful mood prevails throughout most of the first movement which begins with a lively 6/8 melody on the bassoon, contrasted by a change to 2/4 time for the second subject, a lyrical theme shared by piano and bassoon. The second movement, a Ballade, takes us into very different waters: the cheerfulness of the first movement is almost entirely forgotten and, lyrical though the thematic material is, there is an underlying tension giving the music a strange and powerful character. The third movement, a waltz-like Allegretto, dispels this mood somewhat, but not entirely since the final movement opens with a fragment of the second movement's initial theme, this time on solo bassoon in the low register. Even when this dark introduction gives way to a sprightly Vivace, there are still traces of the second movement's thematic material, now transformed into a much brighter character than before. A final brief Animato, a brilliant flourish on the piano, and the work comes to a joyous conclusion.

In earlier days, Elgar played a variety of instruments including the bassoon, and one can sense his affection for the instrument both in his orchestral writing and in his attractive, if somewhat melancholy Romance written at about the same time as the Violin Concerto and dedicated to the bassoonist Edwin James. This is the only solo work Elgar wrote for the instrument, and although originally for bassoon and orchestra, the piano-accompanied version (the composer's own) is particularly successful. Much more recent are Gordon Jacob's Four Sketches, written in 1976. Tinged with the composer's delightful humour, the somewhat fanciful movement titles speak for themselves—A Peaceful Piece (Lento e tranquillo), A Little Waltz (Grazioso alla valse), L'Après-midi d'un dinosaur (Poco lento, pesante) and Polka (Giocoso). The music is published by Emerson Edition.

The remainder of the programme is devoted to French music. Of the four shorter works with which it begins, two are arrangements. Gounod's Funeral March of a Marionette, originally for piano, has been transcribed many times—for orchestra, brass band and organ, for instance—and is here heard in an arrangement for bassoon by Laurence Perkins. The piece received an extra boost of fame some years ago when it was used as the signature tune for a series of Alfred Hitchcock programmes on television, arranged for bassoon quartet. The other arrangement is of the last movement of one of the fifty violin sonatas of Jean-Baptiste Senaillé (1687-1730), or 'Senallié' as it appears on the original editions of the composer's works published during his lifetime. The Allegro spiritoso comes from the Sonata in D minor, Book II, number 5, and acquired fame when the bassoonist Archie Camden recorded an arrangement with orchestra in the days when recordings of Mozart's Bassoon Concerto took five 78rpm sides. The 'fill-up' became more popular than the Concerto and has remained to this day as Archie Camden's 'signature tune'. The arrangement heard on this record is again by Laurence Perkins.

Carignane by Ibert is a wonderful gem of exotic French writing. The work appeared in a collection of short French recital pieces compiled by the great French bassoonist Fernand Oubradous, published in 1953. Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937) belongs to a slightly earlier generation and his Solo de Concert, written in 1898, has all the bravura that one would expect from a late nineteenth-century display piece, along with Pierné's own attractive musical style.

Full of youthful freshness and vitality, it is difficult to believe that the Saint-Saëns Sonata was written when the composer was in his eighty-sixth year. It was, in fact, Saint-Saëns's last composition. Although not a particularly long work it is an attractive and significant item in the bassoon's solo repertoire. As with most of Saint-Saëns's music, the emphasis is on elegant melodic lines and harmonious colours. Of particular interest is the textural originality of the piano part, creating vivid atmospheres from the simplest of musical devices. Nowhere is this better illustrated than at the very beginning of the work where a luminous, rippling accompaniment (consisting of simple arpeggio figures) complements a solo line on the bassoon which combines beauty with a just trace of naïveté. Brief though the movement is, the music still manages to progress through an amazing sequence of keys, finally settling, as it began, in G major to end in a mood of peace and tranquillity. This is abruptly shattered by the opening of the Scherzo—a brilliant piece of virtuoso writing for the bassoon, making considerable technical demands on the performer. However, the gentler, more relaxed passages never allow the listener completely to lose touch with the essentially lyrical character of the work as a whole. The third movement is in two quite distinct sections. The first is an equivalent of a slow movement and is of quite a different character to anything preceding it; this has a lonely, almost barren quality about it, with just a hint of anxiety as the music builds. But this is soon dispelled and the music gains a certain warmth by the end of the section which leads, via the briefest of pauses, into the Finale—probably one of the shortest to be found in music but nevertheless providing the work with an appropriately cheerful ending.

![Chad Lefkowitz-Brown - City Spirit (2026) [Hi-Res] Chad Lefkowitz-Brown - City Spirit (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1772171883_y3mc4z2lmsr7a_600.jpg)

![Lexington - HARD BOP TANGO (2026) [Hi-Res] Lexington - HARD BOP TANGO (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1772180664_cover.jpg)