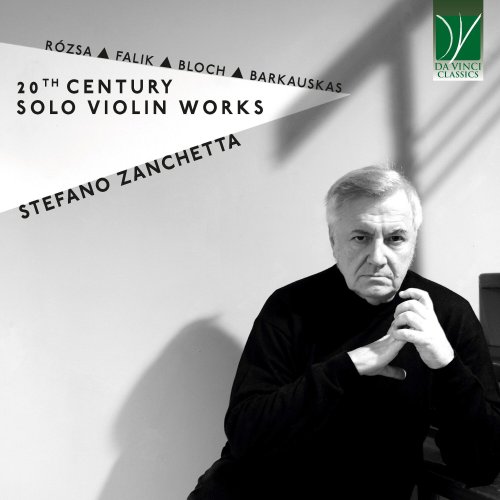

Stefano Zanchetta - Rózsa, Falik, Bloch, Barkauskas: 20th Century Solo Violin Works (2024)

Artist: Stefano Zanchetta

Title: Rózsa, Falik, Bloch, Barkauskas: 20th Century Solo Violin Works

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Violin

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:02:47

Total Size: 333 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Rózsa, Falik, Bloch, Barkauskas: 20th Century Solo Violin Works

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Violin

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:02:47

Total Size: 333 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: I. Allegro moderato

02. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: II. Canzone con variazioni - tema

03. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: III. Var.1 - Poco animato

04. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: IV. Var.2 - Ancora più mosso

05. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: V. Var.3 - Più lento

06. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: VI. Var.4 - Presto

07. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: VII. Var.5 - Allegro

08. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: VIII. Var.6 - Più lento

09. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: IX. Var.7 - Tempo primo

10. Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 40: X. Finale - Vivace

11. Composition for Solo Violin

12. Suite No. 1 for Solo Violin: I. Prelude

13. Suite No. 1 for Solo Violin: II. Andante tranquillo

14. Suite No. 1 for Solo Violin: III. Allegro

15. Suite No. 1 for Solo Violin: IV. Andante

16. Suite No. 1 for Solo Violin: V. Allegro energico

17. Suite No. 2 for Solo Violin: I. Energico, deciso

18. Suite No. 2 for Solo Violin: II. Moderato

19. Suite No. 2 for Solo Violin: III. Andante

20. Suite No. 2 for Solo Violin: IV. Allegro molto

21. Partita for Solo Violin: I. Prelude

22. Partita for Solo Violin: II. Scherzo

23. Partita for Solo Violin: III. Grave

24. Partita for Solo Violin: IV. Toccata

25. Partita for Solo Violin: V. Postlude

The fascinating itinerary to which the listener of this Da Vinci Classics album is invited touches a series of little-known masterpieces written for unaccompanied solo violin in the twentieth century. Although Bach was not the first to state, with his music, that violins did not perforce need the harmonic support of an accompaniment, his six Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin are the first, impressive example of how that belief could be embodied in music. In spite of this, and of the extreme beauty of this cycle, the works it contained had to wait for several decades before gaining acceptance, in their original form, on the concert scene. A kind of horror vacui was felt, and it seemed necessary to provide the solo violin with a background against which it could shine.

In the meantime, however, Niccolò Paganini had written, among others, his Capriccios for unaccompanied solo violin. They developed, and required, an extremely virtuoso technique, with many innovations; yet, their limited size in terms of time lent performers the possibility of playing just excerpts, e.g. as encores or “fillers” within recital programmes with piano accompaniment. (Indeed, this did not prevent them to be provided with piano accompaniments in turn, as had happened with Bach’s Solos: and their “need” for such an accompaniment was felt by such a great musician as Robert Schumann!).

As time went by, the masterpieces by Bach and Paganini were admitted to the concert stage with increasing frequency, and were flanked by new works such as those by Eugène Ysaÿe, to name but one. The twentieth century saw a flowering of such works, as well as the full acceptance of the earlier unaccompanied works into the standard concert repertoire. The works presented here fully deserve the same fate, and it is likely that they will enjoy such a success in the years to come.

The first composers we meet in our pilgrimage is Miklós Rósza. It is not unheard-of for people to obtain immense success in a field which is not the one they themselves love most. For instance, Busoni was immensely admired as a pianist, but his primary love was composition. And, indeed, something similar can be said even of Johann Sebastian Bach, whose fame was bound to the

In the case of Rósza, his success was, and still is, somewhat atypical, inasmuch as his success organ during his lifetime, and only posthumously came to be admired as a composer. was actually due to his compositions, but to those in the field of film music. He was born to a Hungarian bourgeois family, and his mother was a piano teacher who easily guessed her son’s exceptional musical gifts. At six, the child mastered already many secrets of piano-playing, and at 10 he started concertizing. As a youth, he moved to Leipzig where his father wanted him to study chemistry, but, in Bach’s city, he found his lasting vocation and studied with Hermann Grabner for composition and of Th. Kroyer for musicology. He then came back to Hungary where he perfected his skills with Zoltan Kodaly and Béla Bartók.

The recently-graduated youth, however, failed to make a name for himself in his homeland, and, similar to many others, he decided that Paris was the city for hime. There he did obtain success with his solo and orchestra works, and was appointed the Director of a ballet company – to be followed by the directorship of a London theatre. In London, an epoch-making encounter also took place, i.e. that between the world of film music and a musician who would make its history. After his first movie score, he obtained great success with Knight without armour, by fellow Hungarian Alexander Korda. Later, Rósza would write a number of other scores, among which The Thief of Baghdad, Jungle Book, and others for directors such as Billy Wilder and Alfred Hitchcock (for whose Spellbound Rósza was awarded one of the three Academy Awards he received during his lifetime). Many of these were written during Rósza’s years in the United States, starting from little before World War II. In America, Rósza was eventually asked to write music for the kind of movies which best corresponded to his aesthetic, i.e. the epical/grand style of the kolossals (including Quo vadis?, Ivanhoe, and most notably Ben Hur, which brought him another Oscar statuette).

In the last years of his life, however, Rósza felt increasingly the need to leave a legacy of “classical” works for concert performance rather than film music. Possibly the highlight of his career as a classical composer was the premiere of his Viola Concerto at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Hall, with Pinchas Zukerman as the soloist and André Previn conducting. These great musicians were but two of the many who admired Rósza’s work, and which included Jascha Heifetz, Grigory Piatigorski and János Starker. As the title of one of Rósza’s most successful film scores went, the composer had a “double life”, partly dedicated to movies, and partly to composition.

His Sonata for Violin Solo dates from 1986 and is Rósza’s swan song in the field of violin music: his output for this instrument thus spans over nearly sixty years, as his first violin pieces had been written back in 1929. It is dedicated to Manuel Compinsky, a close friend of Rósza, and a violinist the composer trusted so much that he constantly referred to his advice when writing for the violin. About this Sonata, Rósza himself stated: “My music had originally started from folk song, which was melody pure and simple; it would end as melody pure and simple”. He also recollects his impromptu violin playing, accompanied by gypsy musicians, and dedicated to some village beauty, back in Hungary in his youth. As he admitted, “However much I may modify my style in order to write effectively for films, the music of Hungary is stamped indelibly one way or other on virtually every bar I have ever put on paper”. And this folk inspiration is clearly discernible throughout the Sonata, which, in particular, shows the influences of gypsy violin playing techniques. Technically, it is a challenging work requiring double stops, polyphony (melodies over drones), bariolage, and other brilliant virtuoso skills. At times, the piece also evokes the sound of the cymbalon, one of Hungary’s national instruments.

Similar to Rósza, also Yuri Falik had breathed music since his early childhood thanks to the profession of both of his parents, who were orchestral musicians. Also in his case, evidence for his talent surfaced very early, but his childhood was deeply marked by the untimely death of his father during World War II. In Odessa, where Falik and his mother came back from their evacuation in Kyrgyzstan in 1944, the boy studied the cello and was quickly admitted to higher education. Falik soon discovered, in turn, that his greatest musical love was composition, even though he did not relinquish professional cello playing at the highest levels (including a prize at the Tchaikovsky competition, where he would serve, much later, as a jury member). His further education took place in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), where he studied also with Mstislav Rostropovich. He was acquainted with Stravinsky too, who cautioned him against his own “double life” as a cellist and composer, but Falik heeded the master’s advice only partly, focusing more and more on composition but never neglecting his instrument.

His compositional activity became increasingly successful, and included several symphonic works, including three ballets, concertos etc. (and particularly a violin concerto premiered by Grigory Zhislin). He was also inspired by Dmitry Shostakovich, who praised and appreciated his work, but at the same time Falik wished to be independent of Shostakovich’s style which he considered as too personal and self-standing. In his last years, particularly after the fall of the Soviet Union, Falik dedicated more and more of his creative energies to sacred choral music, leaving some masterpieces in this field. He was also an appreciated teacher and he wrote music for fairy tales.

His curiously-titled Composition for unaccompanied violin belongs in a series of similarly named pieces for other instruments. It is a piece where many of the violin’s expressive resources are employed, starting from the whispered beginning and expanding into waves of sound, with a growth involving both pitch and dynamics.

It is instead to Jewish folk and traditional melodies that the music of Ernest Bloch makes constant reference, although he more precisely wished to rediscover the Biblical spirit and exalting the Jewish heritage. A brilliant violinist himself, who had studied with Ysaÿe, Bloch emigrated to the States, where he taught in New York, Cleveland and San Francisco (his best-known pupils include Roger Session and George Antheil), later settling in Switzerland; once more he moved to the US in 1952. This double alternation between Europe and America mirrors the four stylistic stages of his life. And the two Suites recorded here belong in the very last period of his life, after he had been diagnosed with cancer. So deep was Bloch’s engagement with music that he postponed his surgery until the completion of some works he had on his desk. They belong in a series of similar works, which includes three Suites for unaccompanied cello and an unfinished one for viola.

Yehudi Menuhin, who was their dedicatee, described his two Suites as “latter-day Bach Partitas”, in which the composer “continually perfected his contrapuntal technique, doing elaborate and complex mental contrapuntal exercises in his voluminous notebook”. These works were premiered by Alberto Lysy, a pupil of Menuhin, at the Wigmore Hall of London on January 2nd, 1959. Bloch’s daughter Suzanne defines them as “the culmination of Bloch’s musical expression. He ended his life work by writing for the simplest and yet most difficult and complex medium, music for a single instrument”, at a moment when he “was seventy-eight years old, facing death”. In spite of this, “the miracle of the [first] suite is the flow of youth through its pages, its never-ending inspiration and vitality”. Both Suites consists of four movements, seamlessly connected, and both bear resemblances with some earlier works by Bloch (e.g. Voice in the Wilderness, the Violin concerto, and Baal Shem).

The album is completed by a miniature Partita, in five short movements, where some of the best-known dances of the twentieth century are evoked, such as rhumba, blues, and beguine. In this case, then, the object of artistic evocation is Western modern music, rather than Hungarian or Jewish folksong. This calling is answered by Vytautas Barkauskas, one of the most prominent composers in contemporary Lithuania. With a background in mathematics, he was active as a professor of composition for most of his life. His youthful works are very progressive and influenced by the avant-gardes, whilst later he sought a more immediate and very personal musical language. “I do not adhere to one defined compositional system, but I am constantly looking for a natural stylistic synthesis. I aim for my music to be expressive, emotional and concert-like,” said Vytautas Barkauskas.

And the same can be said of each and all of the composers represented here, who drew inspiration from many sources, but ultimately found a unique voice of their own.

![Carwyn Ellis & Rio 18 - Haf (2026) [Hi-Res] Carwyn Ellis & Rio 18 - Haf (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/05/45e3pv7k7wnacsxa569iljs3q.jpg)

![Victoria Alexanyan - VISHAP (2026) [Hi-Res] Victoria Alexanyan - VISHAP (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/06/fp18m8tfhi28on3z9gks3ab7v.jpg)