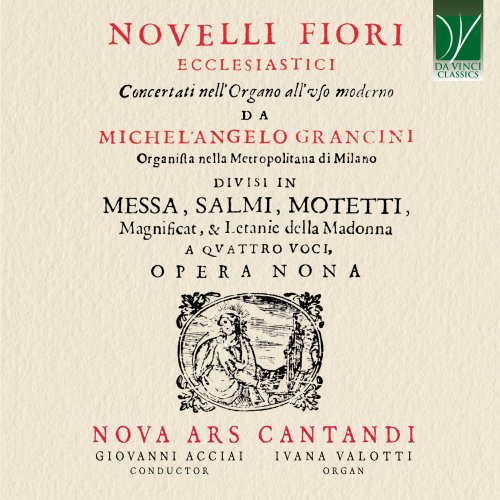

Ivana Valotti, Giovanni Acciai, Nova Ars Cantandi - Michel Angelo Grancini: Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici Opera IX, 1643 (2024) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Ivana Valotti, Giovanni Acciai, Nova Ars Cantandi

Title: Michel Angelo Grancini: Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici Opera IX, 1643

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical, Opera

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:07:39

Total Size: 332 mb / 1.24 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Michel Angelo Grancini: Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici Opera IX, 1643

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical, Opera

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:07:39

Total Size: 332 mb / 1.24 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 1, Exultemus in Domino

02. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 2, Domine, ad adjuvandum

03. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 3, Dixit Dominus

04. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 4, Confitebor tibi Domine

05. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 5, Beatus vir

06. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 6, Laudate pueri

07. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 7, Laudate Dominum

08. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 8, Magnificat. Primo tono

09. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 9, Magnificat breve. Terzo tono

10. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 10, Ecce nunc benedicite

11. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 11, Jubilemus omnes

12. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 12, Audite haec omnes gentes

13. Novelli Fiori Ecclesiastici, Op. 9: No. 13, Exultate gaudio

«Liveliness of ingenuity and musical virtues»

Even in the absence of the baptismal certificate, the birth date of Michel’Angelo Grancini (also known as “Grancino” or “Granzini”), is deduced as 1605, on the basis of two sources: his death certificate and a particular statement contained in the work Ateneo dei Letterati Milanesi (Milan, 1670) by Abbot Filippo Picinelli (1604-1667). From the first document, dated 1669, it is clear that, at the time of his death, Grancini was seventy years old; from the second it is evident that “at the age of 17, being organist in the Church of S. Maria del Paradiso, he began to publish works”. Nothing is known about his family and his early education. It is undeniable that precisely for his great and exceptional musical talents, at just 17 years old, Grancini was deemed eligible for the position of organist at the church of Santa Maria del Paradiso, a well-to-do parish of the old centre of Milan. In 1624, this role was also confirmed by the chapter of the church of the Holy Sepulchre. This Church was designed as seat of the Oblates of Saints Ambrose and Charles, a congregation founded (in 1578) by Cardinal Carlo Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan, one of the most powerful leaders of Counter-Reformation. Not content, Grancini (in 1628) moved to the church of Sant’Ambrogio Maggiore for the post of organist. During this period, the composer published his first sacred music collections: Partitura dell’Armonia Ecclesiastica de Concerti, for one, two, three and four voices, op. I, Milan 1622; Il secondo libro de Concerti, for one, two, three and four voices op. II, Milan, 1624; the third work, unfortunately lost; and Messe, Motetti et Canzoni a otto voci, op. IV, Milan, 1627. The success and prestige received both as organist and as composer lead him to aspire to the most important and prestigeous employement: that is covering one of the two positions of organist at the cathedral of Milan.

In fact, due to the death of Guglielmo Arnone in 1630 (the other organist was Giacomo Filippo Biumi), the Chapter set an organ competition for the first Sunday after Christmas (29 December). Not by chance the excellent musician won the competition and was elected organist, appointment which he held for twenty years, before to be promoted, in 1650, as master of the cathedral chapel. In this task, Grancini assumed the status of Milan’s main composer for major political and civic events until his death on 16 April 1669. It must have been a dramatic moment for Grancini because, at that time, the plague that swept northern Italy (1629-32), loomed over the city causing death pain everywhere. Despite the terrible tragedy the composer did not experience any decline; he was able to give free rein to his creativity continuing in his vast output of sacred music, exclusively dedicated to the usual liturgical service for the Milanese church.

* * *

As shown from the Tavola presented in support of each vocal line and and of organ bass, the Novelli fiori ecclesiastici concertati nell’Organo all’uso moderno, […] divisi in Messa, Salmi, Motetti, Magnificat, et le Letanie della Madonna, for four voices, op. IX (Milan, Giorgio Rolla, 1643), is an anthology of pieces, laid out to satisfy any liturgical need, reflecting an ideal repertoire useful for specific services such as Mass and Divine Office. This sacred collection with its motets (Exultemus in Domino, Ecce nunc, benedicite, Jubilemus omnes, Audite haec omnes gentes; Exultate gaudio), with its psalms (Domine, ad adjuvandum me, festina, Dixit Dominus, Confitebor tibi Domine, Beatus vir, Laudate pueri Dominum, Laudate Dominum omnes gentes) including a Magnificat, first tone, and another short Magnificat, third tone; a Messa concertata (not included in this recording) and Litanie della Madonna, served all sorts of purposes within the context of church services in order to create any type of Vespers. It is not clear why Grancini placed the wording «concertati nell’organo all’uso moderno» on the frontispiece of the print. To be noticed that only few years earlier, following the publication of his sixth work (Sacri fiori concertati a una, due, tre, quattro, cinque, sei et sette voci con alcuni Concerti in Sinfonia d’Istromenti et due Canzoni a quattro. Milan, Giorgio Rolla, 1631) the composer, having expressed his adherence to the stylus modernus, built on Monteverdi’s lesson, was hardly berated. These remarks caused him a lot of pain. Although his reference to “modern usage” in Novelli fiori was mild, since the vocal quartet supported by the organ did not involve the use of instruments and it did not demonstrate inappropriate lexical attitudes or in any case such as to justify an act of censorship, it was enough to get the work not welcome by the Milanese ecclesiastical hierarchies of the time. The “modern” adjective so clearly displayed by Grancini on the first page of this collection was not appreciated from the ecclesiastical environment. In practice, with the use of this specific adjective, the composer had subscribed to the new stylistic and formal demands that were taking shape and becoming established around the middle of the seventeenth century in the north of Italy, but not yet in Milan: the monodic singing and the concertato style. It was a radical change in the musical language as it supplanted the ancient polyphonic idiom of Palestrina’s memory and it rejected the rules established by the Tridentine council on the subject of sacred music.

Hence, Grancini, in an act of contrition, published his tenth work: Musica Ecclesiastica da Cappella a quattro voci, divisa in Messe, Motetti, Magnificat. Aggiuntovi il Basso continuo a beneplacito per l’organo (Milan, Giorgio Rolla, 1645). The intention’s of the author is already manifest not only from the title of the collection buy also through his dedication addressed to the archbishop, Cardinal Cesare Monti, the inflexible continuer of Federico Borromeo’s pastoral action, the one who mocked his music as “effeminate”. The Novelli fiori ecclesiastici concertati nell’Organo all’uso moderno represent the first creative season of our composer, the one characterized by the new stylistic norms emerging around the first half of the 17th century, proceeding along the lines of Monteverdian seconda prattica, that whished to place the words in all their expressive power, in all their emotional sensuality. Just as it was for Monteverdi, so too for Grancini and other composers of his generation, the words were the prime material on which to compose music. The conveying of the meaning of a word by using metaphor to represent an emotional impulse, was the constant guiding principle for every Baroque composer. Grancini demonstrates extraordinary skill in that respect. In fact, since his first publication (1622) until the time as his appointment as Kapellmeister at the cathedral of Milan (1659), Grancini, in his numerous collections of sacred music, reveals a mature, conscious mastery of the most-up-date compositional techniques of the day in the “nuova musica”. His aim is always to exalt the expressive functions of the words, and to highlight the semantic meaning by creating a close association between the sound of the words and the sound of the music. Grancini made no secret of having studied Monteverdi’s music in depth, of making it as his own point of reference and assimilating its communicative power. But his devotion towards the “divine Claudio” did not result in slavish imitation, however, but contributed to his own unmistakable personal style. Unfortunately, by taking on the new role as chapel master of Milan cathedral, Grancini will no longer be able to act in this regard as he once did; he will be forced to change his mind, to gradually return to the ranks of that academic conservatism, of that counter-reformist rigorism which, from a lexical point of view, characterized the sacred music of the Milanese metropolitan church, since the times of Saint Carlo Borromeo and his nephew Federico. In the intonation of the psalmodic texts, Grancini basically follows two composition procedures:

– a constant procedure, in which the psalms (Confitebor tibi Domine, Laudate pueri Dominum, Laudate Dominum omnes gentes) enounce David’s poems uninterruptedly in a single, broad section that is enriched by a constant flow of imitation between the parts;

– a multiple-section procedure, (Domine, ad adjuvandum me, festina, Dixit Dominus, Beatus vir, Magnificat and the Letanie della Madonna), which consists of a sequence of individual section characterised by contrasting style, metrics and agogic, and each linked to a versicle of the psalm or to groups of versicles. The formal patterns followed are related to the concertato style. Even the motets do not escape this approach. In configuring the motifs characterizing the intonation formulas of the psalms (the so-called “psalmodic tones”) Grancini adopt some formal techniques:

– a simple paraphrase of these elements in a polyphonic style, (writing) as the opening of Dixit Dominus;

– an elegant and musical construction in which the motifs become a sort of cantus firmus enriched and embellished with charming countermelodies, as in the opening of Beatus vir and Magnificat, first tone);

– a short fugal expositions, as the opening of Laudate Dominum omnes gentes.

In both cases, in observance with the counter-reformist rules, his intent is always to render the declamation of the religious text clear and comprehensible, privileging the expressiveness of the melody rather than the complexity of the contrapuntal nature. A very good examples in which constant reiterations recurring in order to underly significant words of the Davidic texts (“dominare in medio” of Dixit Dominus; “dispersit dedit pauperibus” of Beatus vir; “quia respexit humilitatem” of Magnificat, first tone) should be read in this light. The poetry of his music is the poetry of spoken language raised to a peak of heat expressive intensity by way of compositional techniques that are not solely a part of composing music but just as much part of the art of oratory, and consequently rhetoric.

The listener can easily identify the infinite range of rhetorical devices (sound figures, figuren für die Einbildungskraft) associated with the effects of the words, where Grancini demonstrates his knowledge and ability to use them appropriately and opportunately. It must be observed how Grancini tackles the relationship between the words and the sound. His art is pure recitation, perfect declamatory eloquence. In the field of this expressive and declamatory style, it is clear that Monteverdi exerted a strong influence on Grancini. Other psalms are in sections with a frequent alternation between solo and tutti: it is the typical contrast that was harbinger of the instrumental baroque concert. This musical idea is developed in some interludes of the psalms such as Confitebor tibi Domine, Laudate pueri Dominum, Letanie della Madonna. These examples not only testify to Grancini’s spontaneous inclination towards a composition always enlivened by lively contrasts and modelled on multi-sectional form but also reveal a mature, conscious mastery of the most up-to-date writing techniques on the field of the «new music ». These techniques were feared perhaps more than the satanic threat by the Ambrosian curia, a Curia that was mindful of the anathema of Saint Carlo: (“the devil lives in brothels, in taverns, in stages, in theaters”). Elsewhere, many psalmodic passages of this collection are enlivened by folk-song themes and dance rhythms. These are not sporadic quotations, but a systemstic use of pre-existing thematic and harmonic material, adopted with the explicit intention of evoking the dance music played in the social life of Milan. Not by chance at the end of his first vocal printed work (1622): Partitura dell’Armonia Ecclesiastica de Concerti, Grancini supports some “Canzoni francesi”. It is interesting to observe some references to the Corrente, for example in the opening section of Domine, ad adjuvandum me, festina; and to note how repeated supplications of the devotional text (for example in the Confitebor, piece in triple time or in the Letanie della Madonna) evoke the dance steps of the Sarabande.

Many other pieces written in stylus vetus are equally rich in ingenious “multi-voice inventions”, and show a skillful, complete, refined technical instrumentation.

The final sections of the psalms (Gloria Patri. Amen) are the passages in which Grancini, whose talent in the field of counterpoint is indisputable, profusely expresses his outstanding ability as a composer of polyphonic music. In this regard, it will be sufficient to mention some paradigmatic examples, the final episode of Confitebor, on the words «et in saecula saeculorum. Amen»; the passage of Beatus vir on “gloria et divitiae in domo ejus” and the “Gloria Patri” of the Magnificat (first tone). As the styles and forms of early seventeenth-century were being established, defined and disseminated across the Po valley, one of the composer who played an active and decisive role in their formation was Michel’Angelo Grancini. His art shines for his proverbial “liveliness of ingenuity and musical virtues”, qualities admired by Picinelli in his aforementioned Ateneo dei Letterati milanesi). Therefore he deserves high consideration, and according to the authoritative judgment of Federico Mompellio “he deserves to be considered one of the most worthy to enter musical history”. The value of Grancini’s art lies in his total adherence to the monteverdian command that the music be serva dell’orazione – serving the expressive demands of the text. Every piece is infused with a refined feeling deriving from Grancini’s response to the words. The words have a hearbeat – syllables and stresses give them their breath, their flatus vocis. Song in turn does not simply fulfil a musical or aesthetic function as a display of beauty. It is the expression of the emotions inherent in the words. It is the supreme manifestation of a techne and a poiesis, an art that Michel’Angelo Grancini possessed to the highest degree. Intus et in cute.

![Dino Siani - I Solisti (2026) [Hi-Res] Dino Siani - I Solisti (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/05/kdog52x9g6c6do3l19wrc5cic.jpg)

![Gabriele Di Franco - The Value of Choices (2026) [Hi-Res] Gabriele Di Franco - The Value of Choices (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772720084_zi78jg17e4q61_600.jpg)