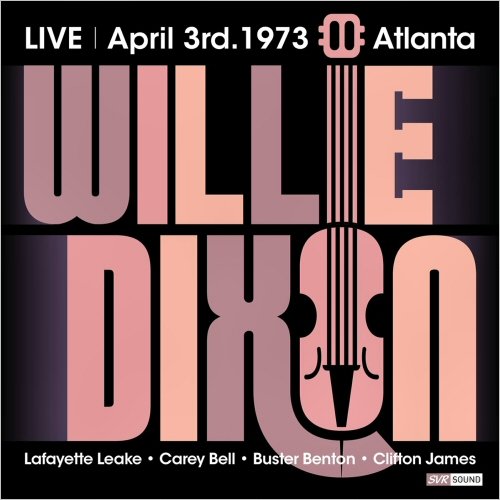

Willie Dixon - Willie Dixon Live At Richard's Atlanta April 3rd. 1973 (Restauracion 2024) (2024)

Artist: Willie Dixon

Title: Willie Dixon Live At Richard's Atlanta April 3rd. 1973 (Restauracion 2024)

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Lantower Records

Genre: Chicago Blues, Piano Blues

Quality: FLAC (tracks) | MP3 320 kbps

Total Time: 74:27

Total Size: 386 MB | 172 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Willie Dixon Live At Richard's Atlanta April 3rd. 1973 (Restauracion 2024)

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Lantower Records

Genre: Chicago Blues, Piano Blues

Quality: FLAC (tracks) | MP3 320 kbps

Total Time: 74:27

Total Size: 386 MB | 172 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Slow Instrumental (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Carey Bell) (7:12)

2. After Hours (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Lafayette Leake) (4:16)

3. Trouble (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Lafayette Leake) (5:46)

4. Everyday I Have The Blues (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Buster Benton) (3:57)

5. Spider In My Stew (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Buster Benton) (5:00)

6. Crazy 'Bout My Baby (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (4:01)

7. Rock Me Shook Me (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (6:03)

8. I Don't Trust Nobody (When It Comes To My Girl) (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Carey Bell) (5:50)

9. Wang Dang Doodle (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (5:41)

10. Fast Instrumental (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (6:26)

11. Everything's Gonna Be Alright (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (5:07)

12. It's Easy To Love (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Buster Benton) (7:52)

13. Good To The Last Drop (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Buster Benton) (3:58)

14. Sweet Sixteen (Fades Out) (Atlanta Live April 3rd. 1973) [Restauracion 2024] (Feat. Buster Benton) (3:12)

Willie Dixon's life and work was virtually an embodiment of the progress of the blues, from an accidental creation of the descendants of freed slaves to a recognized and vital part of America's musical heritage. That Dixon was one of the first professional blues songwriters to benefit in a serious, material way -- and that he had to fight to do it -- from his work also made him an important symbol of the injustice that still informs the music industry, even at the end of the 20th century. A producer, songwriter, bassist, and singer, he helped Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, and others find their most commercially successful voices.

By the time he was a teenager, Dixon was writing songs and selling copies to the local bands. He also studied music with a local carpenter, Theo Phelps, who taught him about harmony singing. With his bass voice, Dixon later joined a group organized by Phelps, the Union Jubilee Singers, who appeared on local radio. Dixon eventually made his way to Chicago, where he won the Illinois State Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship. He might have been a successful boxer, but he turned to music instead, thanks to Leonard "Baby Doo" Caston, a guitarist who had seen Dixon at the gym where he worked out and occasionally sang with him. The two formed a duo playing on street corners, and later Dixon took up the bass as an instrument. They later formed a group, the Five Breezes, who recorded for the Bluebird label. The group's success was halted, however, when Dixon refused induction into the armed forces as a conscientious objector. Dixon was eventually freed after a year, and formed another group, the Four Jumps of Jive. In 1945, however, Dixon was back working with Caston in a group called the Big Three Trio, with guitarist Bernardo Dennis (later replaced by Ollie Crawford).

During this period, Dixon would occasionally appear as a bassist at late-night jam sessions featuring members of the growing blues community, including Muddy Waters. Later on when the Chess brothers -- who owned a club where Dixon occasionally played -- began a new record label, Aristocrat (later Chess), they hired him, initially as a bassist on a 1948 session for Robert Nighthawk. The Chess brothers liked Dixon's playing, and his skills as a songwriter and arranger, and during the next two years he was working regularly for the Chess brothers. He got to record some of his own material, but generally Dixon was seldom featured as an artist at any of these sessions.

Dixon's real recognition as a songwriter began with Muddy Waters' recording of "Hoochie Coochie Man." The success of that single, "Evil" by Howlin' Wolf, and "My Babe" by Little Walter saw Dixon established as Chess' most reliable tunesmith, and the Chess brothers continually pushed Dixon's songs on their artists. In addition to writing songs, Dixon continued as bassist and recording manager of many of the Chess label's recording sessions, including those by Lowell Fulson, Bo Diddley, and Otis Rush. Dixon's remuneration for all of this work, including the songwriting, was minimal -- he was barely able to support his rapidly growing family on the 100 dollars a week that the Chess brothers were giving him, and a short stint with the rival Cobra label at the end of the '50s didn't help him much.

During the mid-'60s, Chess gradually phased out Dixon's bass work, in favor of electric bass, thus reducing his presence at many of the sessions. At the same time, a European concert promoter named Horst Lippmann had begun a series of shows called the American Folk-Blues Festival, for which he would bring some of the top blues players in America over to tour the continent. Dixon ended up organizing the musical side of these shows for the first decade or more, recording on his own as well and earning a good deal more money than he was seeing from his work for Chess. At the same time, he began to see a growing interest in his songwriting from the British rock bands that he saw while in London -- his music was getting covered regularly by artists like the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds, and when he visited England, he even found himself cajoled into presenting his newest songs to their managements. Back at Chess, Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters continued to perform Dixon's songs, as did newer artists such as Koko Taylor, who had her own hit with "Wang Dang Doodle." Gradually, however, after the mid-'60s, Dixon saw his relationship with Chess Records come to a halt. Partly this was a result of time — the passing of artists such as Little Walter and Sonny Boy Williamson reduced the label's roster of older performers, with whom he had worked for years, and the company's experiments with more rock-oriented sounds (especially on the "Cadet Concept" imprint) took it's output in a direction to which Dixon couldn't contribute. And the death of Leonard Chess in the fall of 1969 and the subsequent sale of the company brought about the end of Dixon's relationship to the company.

By the end of the 1960s, Dixon was eager to try his hand as a performer again, a career that had been interrupted when he'd gone to work for Chess as a producer. He recorded an album of his best-known songs, I Am the Blues, for Columbia Records, and organized a touring band, the Chicago Blues All Stars, to play concerts in Europe. Suddenly, in his fifties, he began making a major name for himself on-stage for the first time in his career. Around this time, Dixon began to have grave doubts about the nature of the songwriting contract that he had with Chess' publishing arm, Arc Music. He was seeing precious little money from songwriting, despite the recording of hit versions of such Dixon songs as "Spoonful" by Cream. He had never seen as much money as he was entitled to as a songwriter, but during the 1970s he began to understand just how much money he'd been deprived of, by design or just plain negligence on the part of the publisher doing its job on his behalf.

Arc Music had sued Led Zeppelin for copyright infringement over "Bring It on Home" on Led Zeppelin II, saying that it was Dixon's song, and won a settlement that Dixon never saw any part of until his manager did an audit of Arc's accounts. Dixon and Muddy Waters would later file suit against Arc Music to recover royalties and the ownership of their copyrights. Additionally, many years later Dixon brought suit against Led Zeppelin for copyright infringement over "Whole Lotta Love" and its resemblance to Dixon's "You Need Love." Both cases resulted in out-of-court settlements that were generous to the songwriter.

The 1980s saw Dixon as the last survivor of the Chess blues stable and he began working with various organizations to help secure song copyrights on behalf of blues songwriters who, like himself, had been deprived of revenue during previous decades. In 1988, Dixon became the first producer/songwriter to be honored with a boxed set collection, when MCA Records released Willie Dixon: The Chess Box, which included several rare Dixon sides as well as the most famous recordings of his songs by Chess' stars. The following year, Dixon published I Am the Blues (Da Capo Press), his autobiography, written in association with Don Snowden.

Dixon continued performing, and was also called in as a producer on movie soundtracks such as Gingerale Afternoon and La Bamba, producing the work of his old stablemate Bo Diddley. By that time, Dixon was regarded as something of an elder statesman, composer, and spokesperson of American blues. Dixon eventually began suffering from increasingly poor health, and lost a leg to diabetes. He died peacefully in his sleep early in 1992.

By the time he was a teenager, Dixon was writing songs and selling copies to the local bands. He also studied music with a local carpenter, Theo Phelps, who taught him about harmony singing. With his bass voice, Dixon later joined a group organized by Phelps, the Union Jubilee Singers, who appeared on local radio. Dixon eventually made his way to Chicago, where he won the Illinois State Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship. He might have been a successful boxer, but he turned to music instead, thanks to Leonard "Baby Doo" Caston, a guitarist who had seen Dixon at the gym where he worked out and occasionally sang with him. The two formed a duo playing on street corners, and later Dixon took up the bass as an instrument. They later formed a group, the Five Breezes, who recorded for the Bluebird label. The group's success was halted, however, when Dixon refused induction into the armed forces as a conscientious objector. Dixon was eventually freed after a year, and formed another group, the Four Jumps of Jive. In 1945, however, Dixon was back working with Caston in a group called the Big Three Trio, with guitarist Bernardo Dennis (later replaced by Ollie Crawford).

During this period, Dixon would occasionally appear as a bassist at late-night jam sessions featuring members of the growing blues community, including Muddy Waters. Later on when the Chess brothers -- who owned a club where Dixon occasionally played -- began a new record label, Aristocrat (later Chess), they hired him, initially as a bassist on a 1948 session for Robert Nighthawk. The Chess brothers liked Dixon's playing, and his skills as a songwriter and arranger, and during the next two years he was working regularly for the Chess brothers. He got to record some of his own material, but generally Dixon was seldom featured as an artist at any of these sessions.

Dixon's real recognition as a songwriter began with Muddy Waters' recording of "Hoochie Coochie Man." The success of that single, "Evil" by Howlin' Wolf, and "My Babe" by Little Walter saw Dixon established as Chess' most reliable tunesmith, and the Chess brothers continually pushed Dixon's songs on their artists. In addition to writing songs, Dixon continued as bassist and recording manager of many of the Chess label's recording sessions, including those by Lowell Fulson, Bo Diddley, and Otis Rush. Dixon's remuneration for all of this work, including the songwriting, was minimal -- he was barely able to support his rapidly growing family on the 100 dollars a week that the Chess brothers were giving him, and a short stint with the rival Cobra label at the end of the '50s didn't help him much.

During the mid-'60s, Chess gradually phased out Dixon's bass work, in favor of electric bass, thus reducing his presence at many of the sessions. At the same time, a European concert promoter named Horst Lippmann had begun a series of shows called the American Folk-Blues Festival, for which he would bring some of the top blues players in America over to tour the continent. Dixon ended up organizing the musical side of these shows for the first decade or more, recording on his own as well and earning a good deal more money than he was seeing from his work for Chess. At the same time, he began to see a growing interest in his songwriting from the British rock bands that he saw while in London -- his music was getting covered regularly by artists like the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds, and when he visited England, he even found himself cajoled into presenting his newest songs to their managements. Back at Chess, Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters continued to perform Dixon's songs, as did newer artists such as Koko Taylor, who had her own hit with "Wang Dang Doodle." Gradually, however, after the mid-'60s, Dixon saw his relationship with Chess Records come to a halt. Partly this was a result of time — the passing of artists such as Little Walter and Sonny Boy Williamson reduced the label's roster of older performers, with whom he had worked for years, and the company's experiments with more rock-oriented sounds (especially on the "Cadet Concept" imprint) took it's output in a direction to which Dixon couldn't contribute. And the death of Leonard Chess in the fall of 1969 and the subsequent sale of the company brought about the end of Dixon's relationship to the company.

By the end of the 1960s, Dixon was eager to try his hand as a performer again, a career that had been interrupted when he'd gone to work for Chess as a producer. He recorded an album of his best-known songs, I Am the Blues, for Columbia Records, and organized a touring band, the Chicago Blues All Stars, to play concerts in Europe. Suddenly, in his fifties, he began making a major name for himself on-stage for the first time in his career. Around this time, Dixon began to have grave doubts about the nature of the songwriting contract that he had with Chess' publishing arm, Arc Music. He was seeing precious little money from songwriting, despite the recording of hit versions of such Dixon songs as "Spoonful" by Cream. He had never seen as much money as he was entitled to as a songwriter, but during the 1970s he began to understand just how much money he'd been deprived of, by design or just plain negligence on the part of the publisher doing its job on his behalf.

Arc Music had sued Led Zeppelin for copyright infringement over "Bring It on Home" on Led Zeppelin II, saying that it was Dixon's song, and won a settlement that Dixon never saw any part of until his manager did an audit of Arc's accounts. Dixon and Muddy Waters would later file suit against Arc Music to recover royalties and the ownership of their copyrights. Additionally, many years later Dixon brought suit against Led Zeppelin for copyright infringement over "Whole Lotta Love" and its resemblance to Dixon's "You Need Love." Both cases resulted in out-of-court settlements that were generous to the songwriter.

The 1980s saw Dixon as the last survivor of the Chess blues stable and he began working with various organizations to help secure song copyrights on behalf of blues songwriters who, like himself, had been deprived of revenue during previous decades. In 1988, Dixon became the first producer/songwriter to be honored with a boxed set collection, when MCA Records released Willie Dixon: The Chess Box, which included several rare Dixon sides as well as the most famous recordings of his songs by Chess' stars. The following year, Dixon published I Am the Blues (Da Capo Press), his autobiography, written in association with Don Snowden.

Dixon continued performing, and was also called in as a producer on movie soundtracks such as Gingerale Afternoon and La Bamba, producing the work of his old stablemate Bo Diddley. By that time, Dixon was regarded as something of an elder statesman, composer, and spokesperson of American blues. Dixon eventually began suffering from increasingly poor health, and lost a leg to diabetes. He died peacefully in his sleep early in 1992.

![Paul Mauriat - Après toi (1972) [Hi-Res] Paul Mauriat - Après toi (1972) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/19/7apc8ramq91sp9mgfuj4lcflg.jpg)

![Clifton Chenier - Live at the San Francisco Blues Festival (Live) (1985) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Live at the San Francisco Blues Festival (Live) (1985) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/1okh4wxr3ose6s79w4nxw7vzi.jpg)

![The Mood Mosaic - Acid Maestro (Morricone's Cosmic Funk Legacy) (2025) [Hi-Res] The Mood Mosaic - Acid Maestro (Morricone's Cosmic Funk Legacy) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766134708_dkymenaq6pxqa_600.jpg)