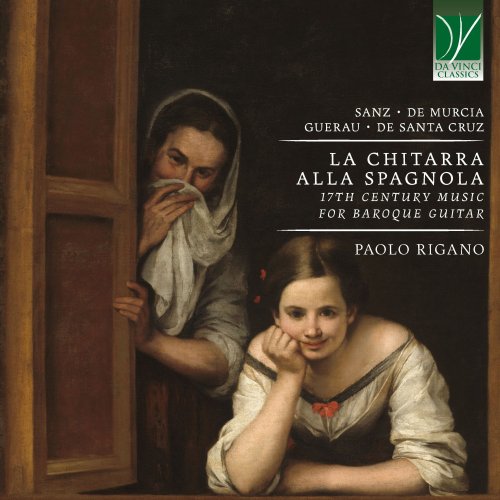

Paolo Rigano - La Chitarra alla Spagnola: 17th Century Music for Baroque Guitar (2024)

Artist: Paolo Rigano

Title: La Chitarra alla Spagnola: 17th Century Music for Baroque Guitar

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:42:13

Total Size: 177 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: La Chitarra alla Spagnola: 17th Century Music for Baroque Guitar

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:42:13

Total Size: 177 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Jacaras

02. Passacalle por la D

03. Fandango

04. Canarios

05. Marionas

06. Zarambeques O Muecas

07. Folias

08. Giga de Corelli

09. Passacalles por la E

10. Jacaras

11. La Jotta

If a crossword puzzle requires to name a country whose musical symbol is the guitar, the solution is rather obvious: Spain. Some of the best guitar makers of the world are found in Spain, as are some of the greatest performers; and doubtlessly a high percentage of the best guitar music ever written has been penned in the Iberian Peninsula.

At the roots of this identification is the glorious history of Baroque guitar, coinciding with the period known as El siglo de oro, the “golden century”, i.e. the seventeenth century. It was a time in which the splendour of Spain shone brightly within Europe, and claimed a place of primacy for the country’s culture, literature, music, painting, etcetera.

Within this framework, the guitar started to affirm itself as one of the musical protagonists, quickly rising to a status which was previously held only by the lute. Some figures of composers and performers of the Baroque guitar stand out as iconic names of the era, and they are all represented in this Da Vinci Classics album. One of the fascinating elements of this recording is that it is played on a Baroque guitar built in Andalusia by luthier Julio Castaños Soler; this richly nuanced instrument, with the authentic sound it provides, allows the performer to propose the variety of shades required by this music and its palette. In order to further promote the immersive listening experience offered by this recording, each piece is introduced by a “prelude”, an improvisation faithfully built on period style and rules, and gently leading the listener into the composition. This corresponds to the practice of the time, and smoothly connects the various items in the programme, inviting listeners to lose themselves in this enthralling recital.

The composer currently known as Gaspar Sanz was actually baptized as Francisco Bartolomé Sanz Celma. While we do not know his exact birth date, it must have been short before his Baptism, which took place on April 4th, 1640, in the church of Calanda de Ebro, in the county of Low Aragon. He was the child of a well-to-do family, which provided him with the best possible education; this was crowned by studies in music, theology, and philosophy at the prestigious and already ancient University of Salamanca. He was ordained a priest and was given a Professorship in Music at the University. This did not prevent him from travelling extensively, and, in particular, to visit several important Italian cities, including Naples and Rome, and possibly Venice. In Italy, he received further musical tuition by some of the most renowned teachers: in Rome, by Orazio Benevoli, chapel master of the Papal choir, and possibly Giacomo Carissimi, and in Naples, by Cristofaro Caresana, who was the organist at the Royal Chapel. Sanz remained in Naples for several years, performing in turn as an organist for the Viceroy, studying guitar with Lelio Colista and learning the secrets of the Italian guitar school from the expertise of such masters as Francesco Corbetta (1615-1681), Giovanni Battista Granata (c. 1620-1687), Giovanni Paolo Foscarini (?-1647).

Back in his native country, Sanz began writing extensively on a variety of subjects. He issued translations of Italian books, (L’huomo di lettere by Daniello Bartoli, 1678), original works (especially in the religious field, but also poetry and other books), and a fundamental treatise in three volumes about guitar playing (issued in individual instalments, and then as a composite work in 1697, by the title of Istrucción de música sobre la guitarra española). He dedicated this work to his pupil Don Juan de Austria (Jr), the illegitimate son of King Philip IV. The treatise’s original title, with its typically (Spanish) Baroque length, is worth quoting in full: “Instruction in Music for the Spanish Guitar and Method of Its First Rudiments, Until Playing It Skillfully, with Two Ingenious Labyrinths, Variety of Tunes and Dances for Strumming and Plucking, in the Spanish, Italian, French, and English Styles, with a Brief Treatise for Accompanying Perfectly on the Very Essential Part for the Guitar, Harp, and Organ, Summarized in Twelve Rules and Examples of the Most Principal Counterpoint and Composition, Dedicated to the Most Serene Lord, Lord Iuan (sic), Composed by the Bachelor Gaspar Sanz, Aragonese, Native of the Town of Calanda, Bachelor in Theology from the Illustrious University of Salamanca”. The words translated here respectively as “strumming” (rasqueado/rasgueado) and “plucking” (punteado) identify two different kinds, styles, and approaches to guitar playing: the former characterized mostly by chord playing, and therefore conceiving the guitar mostly as a harmonic/accompanying instrument, and the latter underpinning the melodic quality of the instrument. The two styles intertwine frequently in Sanz’s work, with a noteworthy flexibility which few other composers of his time can claim to match.

Sanz’s method includes ninety guitar works which are the composer’s only known pieces. Along with dance movements typical for the “international” Baroque (e.g. galliards, passacaglias, pavans), Sanz also included examples of quintessentially Spanish dances, such as the zarabanda, the canarios (an idiomatic dance of the Canary Islands), the jacaras (where echoes from the songs of ox-cart drivers resound). Side by side with “Spanish” works, and with those typical for the European culture of the era, there are also important examples of the traces left in Sanz’s music by his lengthy stay in Italy. Another remarkable trait of this treatise is its system of tablature, derived from Italian schemes but with original elements which are particularly effective and functional.

This treatise and the works contained in it are conceived for proficient players who aim at excellency. It is therefore a treasure chest for today’s musicians in quest of the best music for guitar of Sanz’s era. Themes excerpted from Sanz’s oeuvre became, centuries later, the material on which Joaquín Rodrigo based his extremely famous Fantasía para un Gentilhombre, but Sanz inspired also Manuel de Falla and other great Spanish composers, such as Emilio Pujol.

The great modern fortune of Sanz is unmatched by the history of reception of other composers represented in this album. For instance, Santiago de Murcia has certainly been much appreciated by present-day musicians and scholars, but until very recently only the surface of his biography had been scratched. It is thanks to musicologist Alejandro Vera that we now know more about him.

The element from which all biographies start, in Murcia’s case, is his publication by the title of Resumen de acompañar (Antwerp?, 1714), which is an extremely valuable treatise on accompaniment and figured bass, but which also includes musical works in tablature, mainly excerpted from the famous anthology of dance music published by Feuillet in Paris. The link between Spain and France is due to the presence, at the Spanish court, of a French dance-master, Nicolas Fonton. Other known sources about Murcia are a manuscript in the holdings of the British Library (1732), comprising Passacaglias and other guitar works by a selection of Baroque composers, including Murcia himself, and a codex found in Mexico in 1943. There are also other connections between Murcia and Mexico, leading some musicologist to surmise that the composer finished his days in Latin America. However, recent research suggests, instead, that perhaps only Murcia’s works, and not their author, travelled across the Atlantic; Murcia has been found to have died in Madrid.

Murcia ad also been thought to be the son of a viola and guitar player at the Spanish court, and it was claimed that he came from a musicians’ family; however, Vera’s research shows that his origins were very humble. It has also been surmised that Murcia worked in the theatrical field, and new evidence has been found about his connection to the Queen’s household (something we already knew from the Resumen). Different from what was thought, however, Vera established that his career at court began when the guitarist was already a mature man and a musician of repute.

Murcia’s oeuvre is a very interesting repository of guitar works, and includes not only his own original creations, but also adaptations from the international repertoire of French and Italian music, comprising transcriptions after Corelli’s violin works.

There is a connection with the Spanish court also in the case of Francisco Guerau, whose career took largely part under the wings of Spanish royalty – in this case, as a member of the Royal Chapel Choir. At 10, Francisco – who was a native of Majorca – was admitted to the singing school of the Royal College in Madrid. It provided him with excellent musical education. While most of his fellow students left the school and its choir upon breaking their voice, Francisco managed to keep his place as an alto singer also in his adult age, serving as a teacher as well (from 1693 till 1701); he had been ordained a priest in the early 1680s. His brother Gabriel was also a musician at the Royal Chapel; Francisco was admitted as a member of the Royal Chapel in 1693, the year before the publication of his Poema harmónico compuesto de varias cifras por el temple de la guitarra española (Madrid, 1694). Different from Salz’s work, Guerau’s consists only of pieces in the punteado style, but it provides the reader with a wealth of valuable information about ornamentation, tablatures etc. The works included in the Poema harmónico are all in the form of variations; three quarter of them are pasacalles whose worth is praised by Murcia in his Resumen, whilst the ten remaining ones are examples of a variety of types of Spanish dances. In spite of this, it is important to remember Guerau’s connection with the world of sacred vocal polyphony, due to his duties in the choir, and resulting both in his original vocal works, and in stylistic traits which are more archaic than those of his contemporaries.

Finally, this album includes works by Antonio de Santa Cruz, who was a vihuela and guitar player, and the author of still another treatise/collection, by the title of Libro donde se verán pazacalles de los ocho tonos i de los trasportados (c. 1700). Its introduction reveals the author’s concern with “clean” performance, especially as concerns chord playing. Very little is known about his biography, and his idiomatic system of tablature has frequently discouraged performers from approaching his works. In spite of this, they are absolutely worth knowing and playing, as the recordings in this CD abundantly demonstrate.

![Kaidi Tatham - Miles Away (2025) [Hi-Res] Kaidi Tatham - Miles Away (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1767536832_a2560084361_10.jpg)