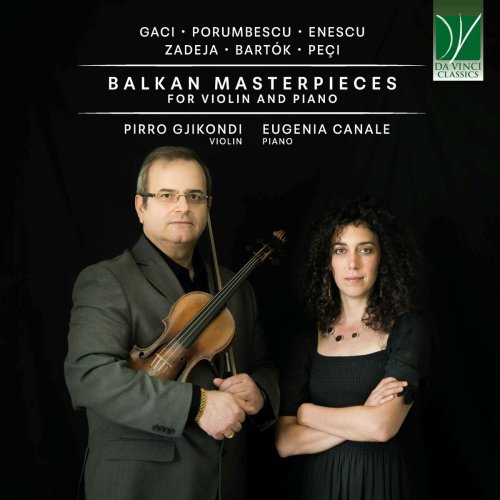

Pirro Gjikondi - Gaci, Porumbescu, Enescu, Zadeja, Peçi, Bartok: Balkan Masterpieces for Violin and Piano (2024)

Artist: Pirro Gjikondi, Eugenia Canale

Title: Gaci, Porumbescu, Enescu, Zadeja, Peçi, Bartok: Balkan Masterpieces for Violin and Piano

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 63:34 min

Total Size: 265 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Gaci, Porumbescu, Enescu, Zadeja, Peçi, Bartok: Balkan Masterpieces for Violin and Piano

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 63:34 min

Total Size: 265 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Preludio, for Violin and Piano

02. Ballade, for Violin and Piano

03. Ballade, for Violin and Piano

04. Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2

05. Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2

06. Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2

07. Sonata for Violin and Piano

08. Sonata for Violin and Piano

09. Romanian Folk Songs for Violin and Piano (Transcription by Zoltán Székely)

10. 3 Albanian Dances for Violin and Piano

The present CD, titled Balkan Masterpieces, features emblematic musical works for violin and piano by Albanian, Romanian, and Hungarian composers, offering a highly synthesized panorama of the musical realities in the respective countries of Southeastern Europe. Pirro Gjikondi (violin) and Eugenia Canale (piano) have sonically outlined paths that appear distinct and dissociated but are connected by a common compositional intent: the dialectic between high art and ethnic humus, or the dialogue between the conventions and principles of the great European tradition and the local conceptions of the new national schools that seek their own stylistic and formal autonomy.

Albanian composer Pietër Gaci (1931–1995) began his studies at the Tirana Music High School (1948–1952) before continuing at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory “P.I. Tchaikovsky,” where he graduated in violin in 1967. He dedicated himself mainly to composition, with a particular focus on instrumental music. His Prelude (1984)—originally for Violin and Orchestra, which influenced the texture’s density in its reduction for piano—is distinguished by the melodic aspect of the solo part and the simplicity and naturalness of expression and formal structure.

After initial training in piano, violin, organ, and cello, Romanian composer Ciprian Porumbescu (1853–1883) completed his studies at the Conservatory of Music and Performing Arts (Vienna) with notable composers such as Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) and Franz Krenn (1816–1897). In his brief life, he left an impressive number of works inspired by folk and urban music. His Ballad for Violin and Orchestra (Ballada pentru vioară și orchestră, completed on 21 October 1880) alternates the highly singable nostalgic meditation of the Andante flébile—a type of langsam (lassan, lassú)—with typical instrumental sections like the Allegro feroce—a type of friska (friss) full of dancing freshness—without, however, confusing it with Hungarian Csárdás or verbunkos. This originality made him well-known and appreciated in the artistic sphere, a fame he leveraged for his political and patriotic activities.

The central core of this production is constituted by the sonatas, a type of composition of Baroque origin, but standardized in its structure during the Enlightenment, which produced an impressive number of works of this genre, later gradually abandoned during the Romantic period, and becoming a rarity in 20th-century Modernism. It should be noted that the progression in Viennese Classicism of the most important instrumental genre of chamber music saw the number of movements increase from the so-called ‘Italian Sonata’ in two parts to the five parts of the mid-19th century. From this perspective, the two—let’s say—“Balkan” sonatas demonstrate a countertrend, with three and two movements respectively, completing the parabola of this genre so crucial for the development of art during the Common Practice Period.

The most important Romanian composer, George Enescu (1881–1955), began an intense activity as a composer, violinist, pianist, and even conductor from the age of five, also extending into pedagogy. The twelve-year-old newly graduated from the Vienna Conservatory (1888–1893)—an institution dominated by the three great Bs, namely: Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms—continued his studies in Paris (1894–1899)—a stage colored by Franck, Saint-Saëns, Massenet, and Fauré—where he performed among the great names of European culture, including Cortot, Ravel, and Bartók. Like most Eastern European artists, Enescu, despite the impressive grandeur of the high culture artistic environment in which he grew up, insisted on integrating the national folk style (styl de la maison) naturally into highly important genres. Thus, the academic principles of mid-European Formenlehre elaborated in the second half of the 19th century intertwined in the works of the ‘incorrigible lyricist’—as the composer liked to call himself—with the morphology of chromatic fluidity in the wake of unendliche Melodie, revealing the debt to Wagnerism so popular in the Germanic world and beyond. With the Second Sonata for Violin and Piano (op. 6, 1899), premiered on 22 February 1900, the young composer felt he was “growing up quickly” to become himself. This work marked not only his compositional maturity but also the entry into the musical world of an important individuality that would tirelessly seek to revise the formal structure of expression without breaking with tradition. Although it would never disappear, this piece marked the beginning of the fading of the exotic fragrance of his early compositions in search of more universal horizons. Formally, the piece has F as its basic tone, articulated in the first two movements in a minor mode, culminating in the last in a major mode. While not adhering to the tonal canons of the cyclic genre, the second movement, an interlude in a broad tripartite form, contrasts with the two lateral movements expressed in sonata form.

After studying at the Moscow Conservatory “P.I. Tchaikovsky” (1952–1956), Çesk Zadeja (1927–1997) carried out significant pedagogical and compositional activities in his homeland. The Albanian musical reality of the second half of the 20th century was under the strict dominance of socialist realism aesthetics, which exerted strong pressure and persecution on any reformist impetus. Only during the years 1971–1981 did some instrumental music works appear that aimed to renew, to some extent, their language, including the Sonata for Violin and Piano (world premiere in May 1974). Despite the basic pentatonic system, predisposed to a modal organization of the anhemitonic type, the pervasive chromaticism provides the harmonic vocabulary with a discreetly dissonant non-tonal background sound. The general instability does not, however, erase polarity, ensuring the necessary contrast to formalize expression in even conventional paradigms. The first movement is articulated in a highly dynamic tripartite form that functions as a prelude to the second and final movement, extended in a sonata form—in terms of sonata-theory—of ‘Type 2’, i.e., sonata form without development, where the second rotation contains, especially regarding the first theme, characteristics of development. Similarly to Enescu’s sonatas, Zadeja’s sonata also shows the immobility of the main tone (D) and, moreover, the mode. The contrast is relegated to the dynamics and rhythm of the solo part, which emphasizes the leading melody, driven by the piano’s ostinato, a pulse labeled drum bass.

With the establishment of comparative musicology (1885)—today: ethnomusicology (1950)—the interest in folk music not only nationally but also of other ethnicities grew exponentially. Hungarian composer Béla [Viktor János] Bartók (Hungary 1881–1945) holds an absolutely unique place, being among the first pioneers to undertake field research, collecting thousands of peasant songs and dances. From these, he not only derived models and stylistic elements of the Variationtrieb (variation pulse) but produced works citing, accompanying, or elaborating on them. Among these, the most notable is the suite of six Romanian Folk Dances (Román népi táncok, Sz. 56, BB 68) with authentic material from Transylvania, initially appearing in the original piano version as Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary (Universal Edition, 1918), later transcribed, with the addition of another dance, for a small orchestral ensemble (Sz. 68, BB 76, 1917, UE 1922). The musical text used for the violin and piano performance is the version—however authorized by the composer—created by Zoltán Székely (UE, 2007).

Despite the added key signature in later publications, the Romanian dances (dansuri românești) are non-tonal music—expressed mostly in Dorian mode, but also Aeolian, Lydian, Mixolydian, with the intertwining even of the Makam with the augmented second—which nevertheless forms a completely homogeneous whole. According to the composer, the deepening of peasant music was “of decisive importance” as it allowed him to look beyond tonality in search of more primitive systems that offered new ways to formalize both melodic expression and harmonic vocabulary.

A graduate of the Tirana Conservatory (1974), Aleksandër Peçi (born 1951) has cultivated a continuous interest in folk songs and dances, producing a series of pieces. A special place in this repertoire is held by the Three Albanian Dances for violin and piano (1978), with melodies from the southeastern area. Although they are independent pieces, they are performed together in a suite form of fast-slow-fast. Thus, it transitions from the kaba tone—a slow and heavy dance—and its paradigmatic aksak rhythm’s cheerfulness in the initial piece, to the cantabile lyricism of the second, ending with the playfulness of the last. The solo part is elaborated by exploiting the instrument’s characteristics and expressive potential in various registers, seeking to differentiate, through the diversification of attack and intensity, the repetitive phrases that distinguish folk melodies.

Edmond Buharaja

Albanian composer Pietër Gaci (1931–1995) began his studies at the Tirana Music High School (1948–1952) before continuing at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory “P.I. Tchaikovsky,” where he graduated in violin in 1967. He dedicated himself mainly to composition, with a particular focus on instrumental music. His Prelude (1984)—originally for Violin and Orchestra, which influenced the texture’s density in its reduction for piano—is distinguished by the melodic aspect of the solo part and the simplicity and naturalness of expression and formal structure.

After initial training in piano, violin, organ, and cello, Romanian composer Ciprian Porumbescu (1853–1883) completed his studies at the Conservatory of Music and Performing Arts (Vienna) with notable composers such as Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) and Franz Krenn (1816–1897). In his brief life, he left an impressive number of works inspired by folk and urban music. His Ballad for Violin and Orchestra (Ballada pentru vioară și orchestră, completed on 21 October 1880) alternates the highly singable nostalgic meditation of the Andante flébile—a type of langsam (lassan, lassú)—with typical instrumental sections like the Allegro feroce—a type of friska (friss) full of dancing freshness—without, however, confusing it with Hungarian Csárdás or verbunkos. This originality made him well-known and appreciated in the artistic sphere, a fame he leveraged for his political and patriotic activities.

The central core of this production is constituted by the sonatas, a type of composition of Baroque origin, but standardized in its structure during the Enlightenment, which produced an impressive number of works of this genre, later gradually abandoned during the Romantic period, and becoming a rarity in 20th-century Modernism. It should be noted that the progression in Viennese Classicism of the most important instrumental genre of chamber music saw the number of movements increase from the so-called ‘Italian Sonata’ in two parts to the five parts of the mid-19th century. From this perspective, the two—let’s say—“Balkan” sonatas demonstrate a countertrend, with three and two movements respectively, completing the parabola of this genre so crucial for the development of art during the Common Practice Period.

The most important Romanian composer, George Enescu (1881–1955), began an intense activity as a composer, violinist, pianist, and even conductor from the age of five, also extending into pedagogy. The twelve-year-old newly graduated from the Vienna Conservatory (1888–1893)—an institution dominated by the three great Bs, namely: Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms—continued his studies in Paris (1894–1899)—a stage colored by Franck, Saint-Saëns, Massenet, and Fauré—where he performed among the great names of European culture, including Cortot, Ravel, and Bartók. Like most Eastern European artists, Enescu, despite the impressive grandeur of the high culture artistic environment in which he grew up, insisted on integrating the national folk style (styl de la maison) naturally into highly important genres. Thus, the academic principles of mid-European Formenlehre elaborated in the second half of the 19th century intertwined in the works of the ‘incorrigible lyricist’—as the composer liked to call himself—with the morphology of chromatic fluidity in the wake of unendliche Melodie, revealing the debt to Wagnerism so popular in the Germanic world and beyond. With the Second Sonata for Violin and Piano (op. 6, 1899), premiered on 22 February 1900, the young composer felt he was “growing up quickly” to become himself. This work marked not only his compositional maturity but also the entry into the musical world of an important individuality that would tirelessly seek to revise the formal structure of expression without breaking with tradition. Although it would never disappear, this piece marked the beginning of the fading of the exotic fragrance of his early compositions in search of more universal horizons. Formally, the piece has F as its basic tone, articulated in the first two movements in a minor mode, culminating in the last in a major mode. While not adhering to the tonal canons of the cyclic genre, the second movement, an interlude in a broad tripartite form, contrasts with the two lateral movements expressed in sonata form.

After studying at the Moscow Conservatory “P.I. Tchaikovsky” (1952–1956), Çesk Zadeja (1927–1997) carried out significant pedagogical and compositional activities in his homeland. The Albanian musical reality of the second half of the 20th century was under the strict dominance of socialist realism aesthetics, which exerted strong pressure and persecution on any reformist impetus. Only during the years 1971–1981 did some instrumental music works appear that aimed to renew, to some extent, their language, including the Sonata for Violin and Piano (world premiere in May 1974). Despite the basic pentatonic system, predisposed to a modal organization of the anhemitonic type, the pervasive chromaticism provides the harmonic vocabulary with a discreetly dissonant non-tonal background sound. The general instability does not, however, erase polarity, ensuring the necessary contrast to formalize expression in even conventional paradigms. The first movement is articulated in a highly dynamic tripartite form that functions as a prelude to the second and final movement, extended in a sonata form—in terms of sonata-theory—of ‘Type 2’, i.e., sonata form without development, where the second rotation contains, especially regarding the first theme, characteristics of development. Similarly to Enescu’s sonatas, Zadeja’s sonata also shows the immobility of the main tone (D) and, moreover, the mode. The contrast is relegated to the dynamics and rhythm of the solo part, which emphasizes the leading melody, driven by the piano’s ostinato, a pulse labeled drum bass.

With the establishment of comparative musicology (1885)—today: ethnomusicology (1950)—the interest in folk music not only nationally but also of other ethnicities grew exponentially. Hungarian composer Béla [Viktor János] Bartók (Hungary 1881–1945) holds an absolutely unique place, being among the first pioneers to undertake field research, collecting thousands of peasant songs and dances. From these, he not only derived models and stylistic elements of the Variationtrieb (variation pulse) but produced works citing, accompanying, or elaborating on them. Among these, the most notable is the suite of six Romanian Folk Dances (Román népi táncok, Sz. 56, BB 68) with authentic material from Transylvania, initially appearing in the original piano version as Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary (Universal Edition, 1918), later transcribed, with the addition of another dance, for a small orchestral ensemble (Sz. 68, BB 76, 1917, UE 1922). The musical text used for the violin and piano performance is the version—however authorized by the composer—created by Zoltán Székely (UE, 2007).

Despite the added key signature in later publications, the Romanian dances (dansuri românești) are non-tonal music—expressed mostly in Dorian mode, but also Aeolian, Lydian, Mixolydian, with the intertwining even of the Makam with the augmented second—which nevertheless forms a completely homogeneous whole. According to the composer, the deepening of peasant music was “of decisive importance” as it allowed him to look beyond tonality in search of more primitive systems that offered new ways to formalize both melodic expression and harmonic vocabulary.

A graduate of the Tirana Conservatory (1974), Aleksandër Peçi (born 1951) has cultivated a continuous interest in folk songs and dances, producing a series of pieces. A special place in this repertoire is held by the Three Albanian Dances for violin and piano (1978), with melodies from the southeastern area. Although they are independent pieces, they are performed together in a suite form of fast-slow-fast. Thus, it transitions from the kaba tone—a slow and heavy dance—and its paradigmatic aksak rhythm’s cheerfulness in the initial piece, to the cantabile lyricism of the second, ending with the playfulness of the last. The solo part is elaborated by exploiting the instrument’s characteristics and expressive potential in various registers, seeking to differentiate, through the diversification of attack and intensity, the repetitive phrases that distinguish folk melodies.

Edmond Buharaja

![The Mood Mosaic - Acid Maestro (Morricone's Cosmic Funk Legacy) (2025) [Hi-Res] The Mood Mosaic - Acid Maestro (Morricone's Cosmic Funk Legacy) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766134708_dkymenaq6pxqa_600.jpg)

![The Mood Mosaic - The Sexploitation (Pulp Grooves From The Mondo Porno Vault) (2025) [Hi-Res] The Mood Mosaic - The Sexploitation (Pulp Grooves From The Mondo Porno Vault) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766131648_uhod8d4qn4msi_600.jpg)

![Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765796826_cover.jpg)