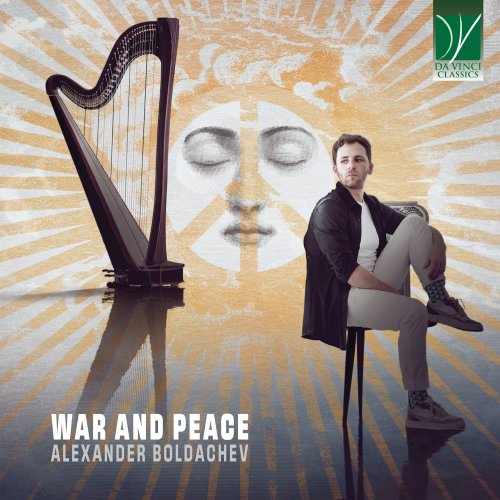

Alexander Boldachev - War and Peace (2024)

Artist: Alexander Boldachev

Title: War and Peace

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Harp

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:10:02

Total Size: 280 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: War and Peace

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Harp

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:10:02

Total Size: 280 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Valse Sentimentale No. 6, Op. 51

02. Promenade from "Pictures at an Exhibition"

03. Nocturne in E-flat Major in E-Flat Major

04. Prelude for Harp in C Major, No. 7 in C Major, Op. 12

05. Prelude in C-Sharp Minor, No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 3

06. Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy from "The Nutcracker"

07. Baba Yaga from "Pictures at an Exhibition"

08. Shchedryk

09. Waltz No. 2 from Suite for Variety Orchestra

10. Chechen Rhapsody

11. Dance of the Knights from "Romeo and Juliet", Op. 64

12. War and Peace

13. Time, Forward!

14. Petruska: Suite

15. The Great Gate of Kyiv from "Pictures at an Exhibition"

Since leaving Russia in March 2022, Alexander Boldachev has lived abroad, separated from his homeland, family, and lifelong friendships. For over two years, he has yearned for the vast lands where he once shared his music. The injustice and devastation of war have profoundly shaped his work, filling it with sorrow and compassion for the people and culture he left behind. Through his charity association “Cultural Solidarity,” he supports refugees from both sides, while his album War and Peace expresses love, loss, and the realization that our world has forever changed.

War and Peace is an intimate album from Swiss-Russian harpist Alexander Boldachev, weaving a narrative of reflection, heritage, and the pursuit of peace. This personal collection is both a testament to his journey and a reflection of humanity’s shared experiences through agitation and tranquility. The album invites listeners into a reflective space, traversing a landscape of “better days” and the haunting dance of life, death, and the spirits in fields of War. Each piece, from Tchaikovsky’s “Sentimental Valse” to Mussorgsky’s “Great Gate of Kyiv,” evokes a poignant narrative — a yearning for the past, an acknowledgment of present pain, and hope for the future. Alexander’s own composition, “War and Peace,” bridges history and nowadays, reflecting on the cycles of human error and unlearned lessons of history. His arrangements of Rachmaninov, Sviridov, and the most virtuoso: Stravinsky’s “Petrushka,” highlight the harp in a new light, showcasing its expressive range like never before.

More than an album, War and Peace is an emotional archive of human experiences, a call to acknowledge our collective responsibility, and a hopeful ode to the potential for peace that lies within us all. It invites listeners to reflect, unite, and work toward a harmonious future.

Alexander Boldachev © 2024

There is in fact a particular connotation of some musical instruments; some seem to be called to express martial or belligerent feelings, others are marked by an entirely different vocation. This is the case with the harp, one of the oldest instruments in human history, and one which has always been deeply bound to poetry, lyricism (actually, the very idea of lyrical poetry implies the presence of the lyre, an instrument akin to the harp!), enchantment, and also religious feelings (as in the case of the poet-king David of Israel).

This album invites listeners into a contemplative space, traversing a landscape marked by the reminiscence of “better days” and the haunting dance of life, death, and the spirits in Ukraine’s fields. Each piece, from Tchaikovsky’s “Sentimental Valse” to Mussorgsky’s “The Old Castle” and “Great Gate of Kyiv”, is carefully selected to evoke a poignant narrative – a yearning for the past, recognition of the present’s pain, and a hopeful gaze into the future.

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition were the result of the composer’s visit to an exhibition commemorating a deceased artist, Viktor Hartmann, who had been Mussorgsky’s friend. The pieces constituting the complete cycle are of two different kinds: the “Promenades” (two of which are longer, the others can consist of just a few bars; the two longer ones divide the cycle into two parts, roughly corresponding to two halves), and the “Pictures” proper. These pieces are musical interpretations of Vladimir Hartmann’s paintings, seen through the lens of Mussorgsky’s own personality. In fact, whereas Hartmann was frequently fascinated by architectural elements, Mussorgsky’s attention was rather drawn to the human figures which the painter had added to his sketches and canvases in order to represent proportions. Furthermore, Mussorgsky’s ordering of the “Pictures” and his division of the cycle into two halves is also meaningful. The Promenades represent the musical depiction of Mussorgsky’s himself. The theme is always the same, symbolizing his personality (and his lopsided walk!), whilst the different harmonizations it undergoes throughout the cycle are evidence of the various feelings he experiences, prompted by Hartmann’s various paintings. These feelings are mainly built on contrasts in the cycle’s first part, whilst the second part of the cycle (whence are taken the two other pieces by Mussorgsky, beyond the Promenade, transcribed here) has a metaphysical meaning. First comes The Marketplace of Limoges, where the colours and sounds of the market represent life at its fullest. It is suddenly followed by a pair of joined pieces, symbolizing death and its toll. Baba Yaga intervenes immediately after. She is a witch from the Russian fairytale tradition, but she is a particularly evil and wicked witch. She lives in a hut on chicken’s legs, and she flies in a mortar, eager to catch mortals, her prey. She symbolizes hell, the devil, the evil; but also myth, i.e. the stories through which human beings try and exorcize the anguish of death. When she seems to triumph – and, in fact, Death devours every living being – the last piece begins. Here Hartmann had portrayed a religious procession passing through a majestic Gate; the sounds of sacred music (organs, choirs, bells) are heard. They “resuscitate” the theme of the Promenade, i.e. Mussorgsky’s musical alter ego, which had been “buried” with his deceased friend in Con mortuis in lingua mortua. This concluding piece thus affirms powerfully that there is Life after death, and that not only will art, and all things beautiful, survive to their creators and keep their memory alive, but also that friends will not be separated from each other forever.

This album also comprises works by other great composers from the East. Tchaikovsky represented the complementary viewpoint on music, in comparison with Mussorgsky’s. Whereas the latter, along with the Mighty Five, promoted a “Russian” kind of Russian music (i.e. to explore the folk roots of Russian music and to create or find a truly national idiom), Tchaikovsky looked West and was more interested in the German-inspired musical culture of the era. His Valse sentimentale is the perfect expression of some of his typical traits: his interest in dance and dance-rhythms, his exceptional gift for melody, his quintessentially Romantic soul. He is also represented here by the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy from “Nutcracker”: it is one of the numerous episodes where magical characters are evoked by the composer’s fascinating and poetical vein, this time with a touch of childlike enchantment which the harp translates in a particularly poignant fashion.

Other works in this CD represent the harp’s formidable capability to render the full texture of a symphonic score. This happens, for instance, with the delightful Waltz excerpted from Dmitri Shostakovich’s Suite for Variety Orchestra, a composition in which the respected “father” of Soviet music ventured into styles and genres which the regime did not fully approve. Shostakovich underwent persecution during the Stalinist era, but he managed generally to remain within the boundaries of the acceptable; at times he confined his critique of the regime to the language of irony, sarcasm, of the grotesque – these languages are the hardest for totalitarian systems to understand!

The enthralling pace of Shostakovich’s Waltz is matched by the equally memorable Dance of the Knights from Prokofev’s Romeo and Juliet. Here the harp will certainly surprise its listeners: even though, as previously said, its vocation is primarily peaceful, it has no problem when the time comes to show power, energy, vigour, and even heroism.

Another dance, this time by Igor Stravinsky, is the one labelled as “Russian” dance in one of the composer’s best-known ballets, Petrushka. It is such a beloved piece that it entered into the concert hall as the first of the Three Movements of Petrushka, compiled by the composer and written for the piano. Here too the percussive elements of both piano and harp are called for, even though the most remarkable feature of this piece is its colourful and robust thematic element.

In still other pieces of this intriguing album, the harp boldly tackles the piano on the latter’s own ground, challenging its “cousin” with struck strings and demonstrating the harp’s potential for massive sonorities. Sergei Rachmaninov’s Prelude op. 3 no. 2 is one of the best-known pieces in piano literature, and it has become a symbol for the grandiosity of the keyboard. The resonance of the harp’s strings shows that this domain is not only the piano’s, but can be fully shared by the plucked strings.

Other pieces were originally written for the harp, such as the Nocturne by Mikhail Glinka. Here the harp showcases its poetical soul, its expressiveness, the utter sweetness of its sounds. It is an enchanted and enchanting piece which is rightfully counted among the “classics” of the harp repertoire.

The Prelude by Prokofev exists in both an original version for harp, played here, and an original version for the piano; the two instruments seem therefore to “intersect” their paths here. But it is rather evident that the composer’s scoring aims at evoking the harp even on the piano, and is therefore much more idiomatic for the harp than for the piano.

The piece by Sviridov is excerpted from a suite coming in turn from the score for a Soviet movie, directed by Sofiya Milkina and Mikhail Schweitzer in 1965. Soviet composers wrote abundantly for the screen, and there was substantial continuity between their output for the concert hall and for the screen. Different from what was happening in the West, where one would hardly imagine Pierre Boulez or Karlheinz Stockhausen as the composers of film music for blockbusters, in the Soviet Union the likes of Shostakovich and Prokofev usually wrote film music, and this field was the major source of income for dissident musicians such as Schnittke.

Last but not least, the album includes some of the harpist’s own compositions, among which “War and Peace”, which serve as a bridge between the past and the present, reflecting on the cyclical nature of human errors and the unlearned lessons of history.

![The Dave Brubeck Quartet - Time Out (1959) [2022 DSD256] The Dave Brubeck Quartet - Time Out (1959) [2022 DSD256]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769324559_folder.jpg)

![Matt Douglas - The Comfort of Repetition (2026) [Hi-Res] Matt Douglas - The Comfort of Repetition (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/24/so8bkng49qgdl58wzljfo4pqa.jpg)

![John Ellis & Double Wide - Fireball (2026) [Hi-Res] John Ellis & Double Wide - Fireball (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769024773_gle3eu5z1g2du_600.jpg)

![Viktoria Tolstoy & Jacob Karlzon - Who We Are (2026) [Hi-Res] Viktoria Tolstoy & Jacob Karlzon - Who We Are (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769523965_folder.jpg)