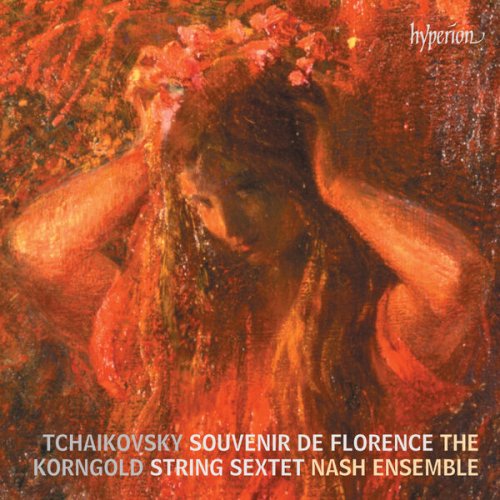

The Nash Ensemble - Tchaikovsky, Korngold: String Sextets (2024) [Hi-Res] [Dolby Atmos]

Artist: The Nash Ensemble

Title: Tchaikovsky, Korngold: String Sextets

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: Dolby Atmos (E-AC-3 JOC) / flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 192.0kHz +Booklet

Total Time: 01:10:09

Total Size: 389 / 354 mb / 2.63 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Tchaikovsky, Korngold: String Sextets

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: Dolby Atmos (E-AC-3 JOC) / flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 192.0kHz +Booklet

Total Time: 01:10:09

Total Size: 389 / 354 mb / 2.63 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Sextet in D Minor, Op. 70, TH 118 "Souvenir de Florence": I. Allegro con spirito

02. Sextet in D Minor, Op. 70, TH 118 "Souvenir de Florence": II. Adagio cantabile e con moto

03. Sextet in D Minor, Op. 70, TH 118 "Souvenir de Florence": III. Allegretto moderato

04. Sextet in D Minor, Op. 70, TH 118 "Souvenir de Florence": IV. Allegro vivace

05. String Sextet in D Major, Op. 10: I. Moderato – Allegro

06. String Sextet in D Major, Op. 10: II. Adagio

07. String Sextet in D Major, Op. 10: III. Intermezzo. Moderato, con grazia

08. String Sextet in D Major, Op. 10: IV. Finale. Presto

The two string sextets paired here are separated by little more than twenty-five years and share a common tonal centre (D), yet they hail from opposite ends of their composers’ careers. Korngold’s sextet received its first performance a few weeks before the composer turned twenty; Tchaikovsky’s ‘Souvenir de Florence’, in contrast, was a late work that was first performed in its revised version less than a year before the Russian’s death. Both works grapple successfully with the challenge of writing for pairs of violins, violas and cellos—‘six independent yet homogenous voices’, as Tchaikovsky described to his brother, Modest. ‘This’, he stated, ‘is unimaginably difficult.’

Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Vospominanie o Florencii (‘Reminiscence of Florence’) is generally much better known than Korngold’s sextet, yet it appears to have given the older, more experienced composer far more trouble to produce. In October 1886, Tchaikovsky had been elected an honorary member of the St Petersburg Chamber Music Society and had promised a piece to Eugen Albrecht in gratitude. Tchaikovsky began initial sketches in June 1887 but soon gave up, having little enthusiasm for the work. He returned to the idea of the sextet in the following years, but did not begin work in earnest until June of 1890, during which time he was renting a house in Frolovskoye, a village in the Klin district of Moscow Oblast. Yet, progress was slow-going, and he remarked to his brother Modest that ‘[I] am writing with difficulty, not for wont of new ideas, but because of the novelty of the form’. Nonetheless, upon the sextet’s completion, he wrote to his patron Nadezhda von Meck of his success in overcoming the challenge and of his pride in the work. Not long after, however, Meck, suffering from a crisis in her finances, ended her patronage—a decision that affected the composer far more deeply emotionally than financially. Moreover, Tchaikovsky continued to worry about his sextet even after finishing it. An initial private performance in November/December 1890 at the Hotel Rossiya in St Petersburg, given by Eugen Albrecht, Franz Hildenbrandt (violins), Oskar Gille, Bruno Heine (violas), Aleksandr Verzhbilovich and Aleksandr Kuznetsov (cellos), was deemed unsatisfactory, and Tchaikovsky resolved to revise the troublesome third and fourth movements, writing in anguish to his brother that ‘the sextet has proved that I’m starting to go downhill’. The changes were made in December 1891 and January 1892 while in Paris, and the revised version received its premiere in December 1892 at the fourth chamber concert of the Russian Musical Society in St Petersburg, where it was performed by Leopold Auer, Hildenbrandt, Emmanuel Kruger, Sergei Korguev, Verzhbilovich and Dmitri Bzul. The sextet’s title was never explained; however, Modest claimed that the beguiling melody heard over pizzicato accompaniment in the andante was sketched in Florence in January 1890 while Tchaikovsky was working on his opera The Queen of Spades.

The opening allegro con spirito, which is cast in a D minor sonata form, is thrillingly tumultuous; indeed, it has the feeling of starting in medias res, the main theme having a curiously circular harmonic characteristic that Benedict Taylor suggests reveals the continuing influence of Schumann, and which allows for plenty of repetition. This harmonic circularity also characterizes the A major second subject, which likewise eschews cadential closure. A development section that climaxes in A flat minor eventually leads us back to a full-throated return of the main theme and re-statement of the second subject in the parallel major. The movement ends with a coda that is underpinned by a long dominant pedal; this is eventually resolved harmonically by a ‘più mosso, vivace assai’ section and a concluding prestissimo as we rush to the finish in unambiguous, symphonic-sounding D minor. The adagio second movement, though, opens unmistakably in the sonorous world of the composer’s earlier Serenade for strings (1880), and Roland John Wiley posits that this self-referentiality is a sign of both compositional lateness and, indeed, Tchaikovsky’s awareness of his mortality and declining health. The graceful ‘Florence’ melody itself is then heard in the first violin in D major, climaxing in a declamatory A major theme. A spooky, texturally unified central D minor section, with surging dynamics and off-beat accents, is followed by a return of the ‘Florence’ melody in the first cello, with the triplet pizzicatos now compressed into semiquavers, and featuring a repeat of the declamatory theme, this time in the home key of D major.

The revised final two movements have a distinctive folk-like character. The allegretto moderato begins with a mournful A minor viola theme that is explored contrapuntally before culminating in a melodic passage of unison cellos, with the other strings providing machine-gun-style chordal accompaniment. The section ends with distinctive repeated pairs of tritone-separated triads (an octatonic progression also beloved of Korngold) that lead to a central cheery A major section which provides a contrasting sparkling vivacity courtesy of its distinctive thrown saltando bowing and pizzicato leaps. A return to the A minor theme combined with elements of the saltando figurations of the central section characterizes the final part of the movement. The work’s closing allegro vivace then begins with a typically Russian-sounding D minor/Aeolian theme but soon shows Tchaikovsky exploring the contrapuntal possibilities of his six instrumental voices. A graceful theme in C major provides temporary respite, but before long Tchaikovsky is drawn back into ‘academic’ developmental procedures. Thus, the centrepiece of the movement is a fugal section that caused the composer considerable unease: despite its strict ‘correctness’, he worried in a letter to Eugen Albrecht about its perceived dissonance. A three-part fugato had been cut from the revised third movement, but this moment of high seriousness survived revisions to the fourth movement. The return of the graceful theme in the home key of D major resolves the remaining harmonic tension of the movement, and Tchaikovsky uses an increased ‘più vivace’ tempo to generate the excitement that takes the work to its conclusion, with the folk-like theme appearing triumphantly in unambiguous D major.

Composition of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s sextet began in 1914 alongside work on Violanta—one of two single-act operas whose first performances in March 1916 heralded the start of Korngold’s meteoric rise to the pinnacle of European operatic life in the early 1920s. Yet, Korngold was also already an established composer of chamber and orchestral works: his Sinfonietta of 1912 had been premiered in Vienna by Felix Weingartner and first performed in Berlin by Arthur Nikisch; and he’d also written a violin sonata for Carl Flesch and Artur Schnabel. This sextet, however, was by far his most ambitious chamber work to date, and it received its first performance in Vienna by the famed Rosé Quartet, supplemented by viola player Franz Jelinek and cellist Franz Klein, on 2 May 1917 in a concert of contemporary chamber music. That first performance programmed the sextet alongside another new Viennese piece—Julius Bittner’s second string quartet—and one of Max Reger’s final works, his clarinet quintet, and was greeted by the Viennese press with its now customary enthusiasm for Korngold’s music. It was published as Korngold’s Op 10 and dedicated to Dr Karl Ritter von Wiener, the President of the Academy for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, who had appointed the youthful Korngold as instructor of operatic dramaturgy and instrumental performance.

After a chromatically spiky opening, the first movement settles into a warm D major sonata-form first theme, perhaps reminding its first Viennese audience of Brahms’s celebrated contributions to the string sextet genre, but equally typical of Korngold’s gift for easy melodiousness. The second theme is in B major over tremolo accompaniment, yet nothing in this movement remains stable for long: surging tempo changes (the movement dictates three distinct tempos) and Korngold’s fondness for large melodic leaps ensure a compelling restlessness throughout. The somewhat ghostly passages of parallel fourths that appear in the middle of the movement show not only Korngold’s appreciation for dramatic special effects that would serve him well in the opera house and movie studio, but also his understanding of the modernist harmony employed by Schoenberg in his recent Chamber Symphony No 1 (1906), echoes of which are apparent elsewhere in this movement. Likewise, suggestions of Korngold’s own Violanta are heard in the declamatory language of the development section, which also provides an opportunity for the composer to try out some contrapuntal writing using a sequential treatment of the work’s opening. The movement then settles back to recapitulate the warmth of the first theme, with the second theme appearing in B flat major, before a slower coda precedes the final rush to a D major closing flourish.

In his youth, Korngold had been hailed a genius by Gustav Mahler, and the Neue Freie Presse’s review of the premiere performance drew explicit connections between the key of the sextet and that of Mahler’s song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. In such contexts, the Mahlerian character of the impassioned opening of the adagio second movement, in which an initial D major sonority is immediately turned into a D minor chord, is difficult to ignore. Indeed, this movement was highlighted by Hans Liebstöckl in a contemporary review for the Prager Tagblatt as the deepest of the sextet’s four movements, and he described it as ‘a broadly rising, voluptuous devotional adagio of imposing journey and great effect’. Again, the echoes of recent Schoenbergian harmony can be heard amidst the restlessness of triplet accompaniment, while Korngold’s fondness for parallel seventh chords is also apparent in an intense passage for the violas and first cello. The luminous G major conclusion to the movement makes use of natural harmonics and Mahlerian portamentos, but its use of harmonies with added sixths and ninths is instantly recognizable from Korngold’s later works.

The intensity of the adagio gives way to a charming F major intermezzo whose Viennese character was immediately apparent to contemporary commentators: Der Morgen’s reviewer identified it as a place ‘where elves, gnomes and other good and evil spirits of the Vienna Woods twirl in undulating waltz rhythms’, while the Neue Freie Presse noted its popularity with the audience. Harmonically, the intermezzo makes striking use of chromatic mediant progressions (such as F major to D flat major), while the frequent contrasts in mood and tempo might indicate more Mahlerian influences. Mahlerian fragmentation also characterizes the quirky ending, in which an attempt to restart the movement’s main waltz theme quickly breaks down. If the intermezzo is full of Viennese charm, though, the sonata-form finale is quite simply one of Korngold’s most joyous creations, in which the players are instructed to play ‘as fast as possible with fire and humour’. It returns to the sextet’s D major home key, and presents a cheerful, fanfare-like first theme that’s passed between the first cello and first violin with exciting motoric accompaniment in the remaining parts. More chromatic mediant progressions of a sort that would become a particular harmonic signature of the composer are heard alongside off-beat accents as the melody fragments, before a sprightly second theme is presented by the first cello in E flat major, with comic octave interruptions from the violins and violas. More spirited textures are heard during a development section that includes passages of col legno, and which leads to a climax that features a reminiscence of the first movement’s opening figure, before the music launches back into a recapitulation of the main theme, with the second subject now presented in its traditional D major. There then follows a remarkable apotheosis in which the tempo slows, and all instruments eventually play double- and triple-stopped chords in a squeezebox-like texture. The music thereafter rushes to a breathtaking finish, making a last passing reference to the first movement’s main theme before the finale’s own fanfare theme brings matters to a close.

![Nābu Pēra - Soundscapes of Nicosia (2025) [Hi-Res] Nābu Pēra - Soundscapes of Nicosia (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/14/lhs20jten1ip5ht0uibyjocfe.jpg)

![Nectar Woode - Live at Village Underground (Live At Village Underground) (2025) [Hi-Res] Nectar Woode - Live at Village Underground (Live At Village Underground) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/15/eiazyx7yigt2lhbv1tcd3eos6.jpg)