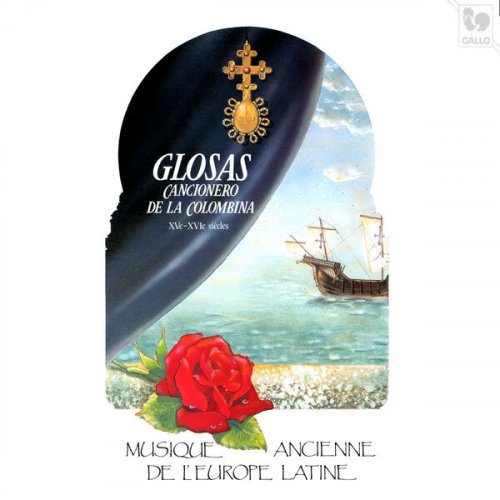

Ensemble Glosas - Cancionero de la Colombina (2024) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Ensemble Glosas

Title: Cancionero de la Colombina

Year Of Release: 1986 / 2024

Label: VDE-GALLO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 42:18

Total Size: 818 / 202 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Cancionero de la Colombina

Year Of Release: 1986 / 2024

Label: VDE-GALLO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 42:18

Total Size: 818 / 202 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Cancionero de la Colombina: 57 Propiñán de Melyor (00:51)

2. Cancionero de la Colombina: 91 Juyzio Fuerte Será Dado (00:56)

3. Cancionero de la Colombina: 73 Juyzio Fuerte Será Dado (00:33)

4. Cancionero de la Colombina: 52 Olvida tu Perdiçión (01:29)

5. Cancionero de la Colombina: (sin título) [I] (01:15)

6. Cancionero de la Colombina: 89 Aquella Buena Mujer (01:56)

7. Cancionero de la Colombina: 88 Por Bever, Comadre (01:03)

8. Cancionero de la Colombina: 71 La Moça Que Las Cabras Cría (01:49)

9. Cancionero de la Colombina: 14 Qu'es Mi Vida Preguntáys (05:03)

10. Cancionero de la Colombina: 95 No Tenga Con Vos Amor (01:05)

11. Cancionero de la Colombina: 16 Mis Tristes Sospiros (03:05)

12. Cancionero de la Colombina: 48 Dime, Triste Coraçón (02:28)

13. Cancionero de la Colombina: 2 Pues Con Sobra De Tristura (03:16)

14. Cancionero de la Colombina: 51 Pensamiento, Ve Do Vas (01:38)

15. Cancionero de la Colombina: 31 Mirando, Dama Fermosa (03:53)

16. Cancionero de la Colombina: (sin título) [II] (01:07)

17. Cancionero de la Colombina: 66 Deus in adjutorium (01:59)

18. Cancionero de la Colombina: 70 Pinguele, Rrespinguete (01:07)

19. Cancionero de la Colombina: 79 Dic nobis, María (I) (00:22)

20. Cancionero de la Colombina: 78 Ay, Santa María, Valedme (00:26)

21. Cancionero de la Colombina: 79 Dic nobis, María (II) (00:25)

22. Cancionero de la Colombina: 55 O Gloriosa Domina (01:01)

23. Cancionero de la Colombina: 79 Dic nobis, María (III) (00:25)

24. Cancionero de la Colombina: 75 Qué Bonito Niño Chiquito (01:09)

25. Cancionero de la Colombina: 90 Dinos, Madre Del Donsel (02:24)

26. Cancionero de la Colombina: 72 A Los Maytines (01:19)

At the end of the XVth century, Spain stands at the crossroads of History. Leaving deep marks in the Iberian soul, the triple civilization (Judaic, Arabian, Christian) is coming to its end. In 1492, the «Catholic Kings», Fernando de Aragon and Isabel de Castilla, seize Granada, the last Arabian stronghold on the Peninsula, and also reunify Spain after seven centuries of struggle for freedom and conflict of belief. The same year signals the beginning of a new era for civilization. The discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in the Catholic Kings’ service, and the great adventure deriving from it, place Spain at the head of the European states.

The Cancionero of the Biblioteca Colombina in Sevilla, a manuscript from the end of the XVth century, illustrates musically the national spirit developing among the Spaniards. In this anthology of chansons and romances, «Cantilenas vulgares puestas en musica por varios Españoles», a truly Spanish style begins to separate itself from the Dutch style which dominated the musical taste of this period. The Franco-Netherlandish influence on polyphony loses ground before the simplicity of the new Spanish chanson: using popular forms and themes and homophonic writing, Spanish musicians prefer to arouse deep aesthetic emotions with a minimum of technical complexity. Thus, the choice of profoundly moving poetical texts for the love songs (the greatest part of this collection) contributes to the creation of a typically national «genre» of chanson, different from the Franco-Netherlandish chanson in fashion at the court of Burgundy.

This Cancionero, more than the famous Cancionero de Palacio, stands at the turning point of two periods: pieces of strict polyphony (Qu’es mi vida preguntays) appear side by side with Christmas songs of extreme simplicity; the resolutely «renaissance» character of the one style (Dime triste coraçon) contrasts with the cadences in thirds of the other, more ancient one. There is also a difference in the disposition of the parts and the instrumentation: in the contrapuntal pieces, the top part bears the words while the lower parts are instrumental; on the other hand, in the more homophonic songs, all the parts can be sung with the text; other pieces have different texts meant to be sung at the same time by two singers, in the manner of an «ensalada» (La moça que las cabras cria); they sometimes associate a religious and a secular text (Retorno a lo divino). All this gives a great variety to the Cancionero; it has allowed us to divide it into six principal themes, five of which (leaving out the religious polyphony) build the various groups on this record.

Among the 95 or so pieces of this anthology, we find more than 40 songs of love and sadness, ten with an ironical or satirical text, a dozen dedicated to the Virgin and the Child, twelve in Latin, some pieces of an epic character and seven without any text, probably instrumental ones. Most of the compositions are in three parts, the four parts being reserved for the solemn pieces (religious or epic) or for the later ones, written in the homophonic style (Pensamiento, ve do vas).

The composers of the Cancionero, except Ockeghem (co-author with Cornago of «Qu’es mi vida preguntays») and Urrede, are all Spanish. The most prolific is Juan de Triana, represented by twenty compositions (seven on this record) and whose importance here can be compared to that of Juan del Encina in the Cancionero del Palacio. Enrique, Francisco de la Torre and the anonymous writers, who have given us beautiful love songs, complete the list of composers.

We have chosen the instrumentations in relation to the character of the pieces and their social function. The «unmixed consort» linked to polyphony is a characteristic feature of the XVIth century, while the flexibility of the three parts in our Cancionero requires very often the use of different – though related – instruments. Thus for the love chansons we play on the low instruments: vihuela de arco, viols, lutes, harps and recorders, while the high instruments – shawms, sackbutt and organ – take their part in religious festivities and important events, following a practice common all through the XVth century.

On the eve of the Renaissance, the Cancionero de la Colombina is a Spanish picture of European music; it announces the growth of Spain and her national music, which is to reach its climax in the next century, taking a place of honour in Music History.

The Cancionero of the Biblioteca Colombina in Sevilla, a manuscript from the end of the XVth century, illustrates musically the national spirit developing among the Spaniards. In this anthology of chansons and romances, «Cantilenas vulgares puestas en musica por varios Españoles», a truly Spanish style begins to separate itself from the Dutch style which dominated the musical taste of this period. The Franco-Netherlandish influence on polyphony loses ground before the simplicity of the new Spanish chanson: using popular forms and themes and homophonic writing, Spanish musicians prefer to arouse deep aesthetic emotions with a minimum of technical complexity. Thus, the choice of profoundly moving poetical texts for the love songs (the greatest part of this collection) contributes to the creation of a typically national «genre» of chanson, different from the Franco-Netherlandish chanson in fashion at the court of Burgundy.

This Cancionero, more than the famous Cancionero de Palacio, stands at the turning point of two periods: pieces of strict polyphony (Qu’es mi vida preguntays) appear side by side with Christmas songs of extreme simplicity; the resolutely «renaissance» character of the one style (Dime triste coraçon) contrasts with the cadences in thirds of the other, more ancient one. There is also a difference in the disposition of the parts and the instrumentation: in the contrapuntal pieces, the top part bears the words while the lower parts are instrumental; on the other hand, in the more homophonic songs, all the parts can be sung with the text; other pieces have different texts meant to be sung at the same time by two singers, in the manner of an «ensalada» (La moça que las cabras cria); they sometimes associate a religious and a secular text (Retorno a lo divino). All this gives a great variety to the Cancionero; it has allowed us to divide it into six principal themes, five of which (leaving out the religious polyphony) build the various groups on this record.

Among the 95 or so pieces of this anthology, we find more than 40 songs of love and sadness, ten with an ironical or satirical text, a dozen dedicated to the Virgin and the Child, twelve in Latin, some pieces of an epic character and seven without any text, probably instrumental ones. Most of the compositions are in three parts, the four parts being reserved for the solemn pieces (religious or epic) or for the later ones, written in the homophonic style (Pensamiento, ve do vas).

The composers of the Cancionero, except Ockeghem (co-author with Cornago of «Qu’es mi vida preguntays») and Urrede, are all Spanish. The most prolific is Juan de Triana, represented by twenty compositions (seven on this record) and whose importance here can be compared to that of Juan del Encina in the Cancionero del Palacio. Enrique, Francisco de la Torre and the anonymous writers, who have given us beautiful love songs, complete the list of composers.

We have chosen the instrumentations in relation to the character of the pieces and their social function. The «unmixed consort» linked to polyphony is a characteristic feature of the XVIth century, while the flexibility of the three parts in our Cancionero requires very often the use of different – though related – instruments. Thus for the love chansons we play on the low instruments: vihuela de arco, viols, lutes, harps and recorders, while the high instruments – shawms, sackbutt and organ – take their part in religious festivities and important events, following a practice common all through the XVth century.

On the eve of the Renaissance, the Cancionero de la Colombina is a Spanish picture of European music; it announces the growth of Spain and her national music, which is to reach its climax in the next century, taking a place of honour in Music History.

![Inclusion Principle - Third Opening (2020) [Hi-Res] Inclusion Principle - Third Opening (2020) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/21/p8lsxgh9c05zvfinms5mdctxz.jpg)

![Nicolas Collins & Birgit Ulher - Spark Gap (2026) [Hi-Res] Nicolas Collins & Birgit Ulher - Spark Gap (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769148924_vicc2td18xrvc_600.jpg)