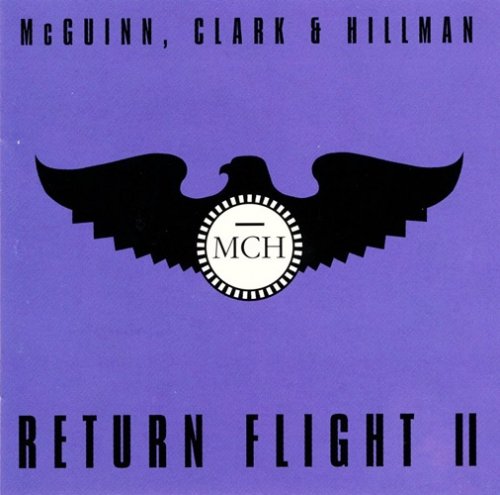

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman - Return Flight II (1993)

- 12 Jan, 13:40

- change text size:

Facebook

Twitter

Artist: McGuinn, Clark, Hillman

Title: Return Flight II

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Edsel Records

Genre: Classic Rock, Country Rock, Folk Rock

Quality: Flac (tracks)

Total Time: 01:00:01

Total Size: 385 Mb (scans)

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Return Flight II

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Edsel Records

Genre: Classic Rock, Country Rock, Folk Rock

Quality: Flac (tracks)

Total Time: 01:00:01

Total Size: 385 Mb (scans)

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Little Mama 4:13

02. Stopping Traffic 3:18

03. Feelin' Higher 5:20

04. Release Me Girl 3:50

05. Bye Bye, Baby 3:59

06. One More Chance 4:08

07. Won't Let You Down 3:57

08. Street Talk 2:47

09. Deeper in 2:42

10. Painted Fire 2:49

11. Mean Streets 2:58

12. Entertainment 3:24

13. Soul Shoes 3:11

14. Love Me Tonight 3:14

15. Secret Side of You 3:42

16. Ain't No Money 3:30

17. Making Movies 3:00

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman (later McGuinn-Hillman) came about in 1977, when three former members of the original Byrds -- Roger McGuinn, Gene Clark, and Chris Hillman -- decided to try and update their sound in a new context. The impetus for the reunion took shape in stages over the course of that year. McGuinn and Hillman had played together longer than any of the other original members, with six albums (and innumerable concerts) across four years during the 1960s, and as late as 1967 they'd tried without success to reintegrate Gene Clark -- the best songwriter among them and a superb singer, but also the first to leave -- back into the band. Then, in early 1977, with each fronting his own band, they planned a joint tour of Europe promoting their own respective new releases. The Byrds were still idolized across Europe, even more so than in the United States, and ticket sales were brisk and press coverage enthusiastic.

The actual tour didn't go off exactly as planned, owing to Clark's ever-present personal (and psychological) demons on one end and Hillman's business disputes with the promoter on the other. But the experience of singing together on-stage for the first time in more than ten years, as they did at two successive shows at London's Hammersmith Odeon, was so satisfying to all three that McGuinn and Clark ended up touring the United States together as a duo; they were joined at some performances by Hillman (and even fellow original Byrd David Crosby occasionally showed up at their performances, most notably at the Boarding House in San Francisco, the latter becoming an unofficial Byrds reunion, captured in a radio broadcast and later released as the bootleg Doin' All Right for Old People). Those mostly West Coast "reunion" shows happened to be witnessed by representatives of various record labels, including Rupert Perry, then the president of Capitol Records. The latter company signed McGuinn and Clark up as a duo in late 1977, with Hillman -- newly released from his contract with Asylum Records -- coming aboard soon after.

On its face, the idea seemed brilliant, getting three of the original group's four principal singer/songwriters together. But there were also serious flaws in the plan from the start -- in announcing the existence of the trio to the world, McGuinn and company stated that they were not planning to rehash the Byrds sound, but to make records that were contemporary and forward-looking -- this reunion was about the here-and-now and the future, not the past. But putting those three musicians together inevitably raised expectations among the most likely record-buyers and concertgoers, of something akin to a Byrds reprise. As though to dash those hopes and establish themselves as a new performing unit, the resulting debut album, McGuinn, Clark & Hillman, made heavy use of additional singers and musicians, and McGuinn's trademark 12-string Rickenbacker guitar was nowhere in evidence. The music was pleasant, reminiscent at times of the Eagles and Firefall (the latter, ironically, the home of ex-Byrds drummer Michael Clarke), but also a bit stiff.

What's more, the occasional presence of a disco beat on some of the songs didn't seem to please any part of the audience, while the group's avoiding any semblance of the Byrds' sound, vocally or instrumentally, seemed like an insult to peoples' tastes and expectations. And none of that would have seemed quite so bad, if only they had replaced their expected sound with something musically viable and justified -- but warmed-over Eagles with a disco beat was barely that. Matters weren't helped at all by the subsequent tour, on which the trio did, indeed, acknowledge and utilize its classic Byrds sound, even performing parts of that old repertory. The most loyal part of their audience could, understandably, feel some confusion and frustration over the fact that the performing version of McGuinn, Clark & Hillman seemed to embrace a difference sound from the record they'd made -- which made purchasers of that record feel frustrated and disappointed, even with a modest hit single, "Don't You Write Her Off," which charted at number 33. And then Gene Clark's health began deteriorating, forcing his exit from the tour.

This event created a rift between the ex-bandmates that was never fully healed, and may well have been responsible for Clark's not having been asked to participate in the "reunion" tracks recorded for the Byrds box set in the early '90s. McGuinn and Hillman soldiered on to finish the tour and do a second album, entitled City. Released in 1980, and created to McGuinn & Hillman "featuring Gene Clark," it had more of a recognizable connection to the Byrds, and was as strong a record as -- and some would say even stronger than -- its predecessor. But even here, there were some serious weaknesses, as Clark's two songs, one of them ironically called "Don't Let You Down," were the two best tracks on the album. Additionally, although this record did sound a bit more in keeping with the history of the musicians involved, some of the material seemed inappropriate, even silly -- "Skate Date" was catchy enough, but hardly worthy of (or appropriate) for two singer/songwriters associated with such songs as "Eight Miles High," "The Girl with No Name," "Have You Seen Her Face," etc.

City was successful enough to justify a third release, simply called McGuinn/Hillman, but that record proved a group-breaker -- the producers, Jerry Wexler and Barry Beckett, were renowned R&B specialists who evidently just didn't embrace the Byrds' sound or its modern permutations, and neither musician was comfortable with the results. It wasn't that the Byrds had never touched on aspects of '50s R&B -- they'd successfully applied a 12-string-driven Bo Diddley beat to "Don't Doubt Yourself, Babe" in 1965 -- but the record, despite a few distinctive moments, mostly in the songs written by McGuinn and Hillman, just didn't feel like it represented the people or the talents on it.

In the wake of the group's folding in 1981, Chris Hillman returned to bluegrass, where he had started his career, and later won several country music awards and cut a string of successful albums with the Desert Rose Band. Meanwhile, Roger McGuinn resumed his solo career, playing the occasional concert and eventually cutting a fairly successful album, Back from Rio. Gene Clark toured nationally with a band called the Firebyrds and cut one album (with another left unfinished) for Allegiance Records in the early '80s, and subsequently recorded with Carla Olson, but he never really resumed a full-time career. He died in 1991, just a few months after taking the stage with McGuinn, Hillman, and David Crosby at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony honoring the Byrds.

The actual tour didn't go off exactly as planned, owing to Clark's ever-present personal (and psychological) demons on one end and Hillman's business disputes with the promoter on the other. But the experience of singing together on-stage for the first time in more than ten years, as they did at two successive shows at London's Hammersmith Odeon, was so satisfying to all three that McGuinn and Clark ended up touring the United States together as a duo; they were joined at some performances by Hillman (and even fellow original Byrd David Crosby occasionally showed up at their performances, most notably at the Boarding House in San Francisco, the latter becoming an unofficial Byrds reunion, captured in a radio broadcast and later released as the bootleg Doin' All Right for Old People). Those mostly West Coast "reunion" shows happened to be witnessed by representatives of various record labels, including Rupert Perry, then the president of Capitol Records. The latter company signed McGuinn and Clark up as a duo in late 1977, with Hillman -- newly released from his contract with Asylum Records -- coming aboard soon after.

On its face, the idea seemed brilliant, getting three of the original group's four principal singer/songwriters together. But there were also serious flaws in the plan from the start -- in announcing the existence of the trio to the world, McGuinn and company stated that they were not planning to rehash the Byrds sound, but to make records that were contemporary and forward-looking -- this reunion was about the here-and-now and the future, not the past. But putting those three musicians together inevitably raised expectations among the most likely record-buyers and concertgoers, of something akin to a Byrds reprise. As though to dash those hopes and establish themselves as a new performing unit, the resulting debut album, McGuinn, Clark & Hillman, made heavy use of additional singers and musicians, and McGuinn's trademark 12-string Rickenbacker guitar was nowhere in evidence. The music was pleasant, reminiscent at times of the Eagles and Firefall (the latter, ironically, the home of ex-Byrds drummer Michael Clarke), but also a bit stiff.

What's more, the occasional presence of a disco beat on some of the songs didn't seem to please any part of the audience, while the group's avoiding any semblance of the Byrds' sound, vocally or instrumentally, seemed like an insult to peoples' tastes and expectations. And none of that would have seemed quite so bad, if only they had replaced their expected sound with something musically viable and justified -- but warmed-over Eagles with a disco beat was barely that. Matters weren't helped at all by the subsequent tour, on which the trio did, indeed, acknowledge and utilize its classic Byrds sound, even performing parts of that old repertory. The most loyal part of their audience could, understandably, feel some confusion and frustration over the fact that the performing version of McGuinn, Clark & Hillman seemed to embrace a difference sound from the record they'd made -- which made purchasers of that record feel frustrated and disappointed, even with a modest hit single, "Don't You Write Her Off," which charted at number 33. And then Gene Clark's health began deteriorating, forcing his exit from the tour.

This event created a rift between the ex-bandmates that was never fully healed, and may well have been responsible for Clark's not having been asked to participate in the "reunion" tracks recorded for the Byrds box set in the early '90s. McGuinn and Hillman soldiered on to finish the tour and do a second album, entitled City. Released in 1980, and created to McGuinn & Hillman "featuring Gene Clark," it had more of a recognizable connection to the Byrds, and was as strong a record as -- and some would say even stronger than -- its predecessor. But even here, there were some serious weaknesses, as Clark's two songs, one of them ironically called "Don't Let You Down," were the two best tracks on the album. Additionally, although this record did sound a bit more in keeping with the history of the musicians involved, some of the material seemed inappropriate, even silly -- "Skate Date" was catchy enough, but hardly worthy of (or appropriate) for two singer/songwriters associated with such songs as "Eight Miles High," "The Girl with No Name," "Have You Seen Her Face," etc.

City was successful enough to justify a third release, simply called McGuinn/Hillman, but that record proved a group-breaker -- the producers, Jerry Wexler and Barry Beckett, were renowned R&B specialists who evidently just didn't embrace the Byrds' sound or its modern permutations, and neither musician was comfortable with the results. It wasn't that the Byrds had never touched on aspects of '50s R&B -- they'd successfully applied a 12-string-driven Bo Diddley beat to "Don't Doubt Yourself, Babe" in 1965 -- but the record, despite a few distinctive moments, mostly in the songs written by McGuinn and Hillman, just didn't feel like it represented the people or the talents on it.

In the wake of the group's folding in 1981, Chris Hillman returned to bluegrass, where he had started his career, and later won several country music awards and cut a string of successful albums with the Desert Rose Band. Meanwhile, Roger McGuinn resumed his solo career, playing the occasional concert and eventually cutting a fairly successful album, Back from Rio. Gene Clark toured nationally with a band called the Firebyrds and cut one album (with another left unfinished) for Allegiance Records in the early '80s, and subsequently recorded with Carla Olson, but he never really resumed a full-time career. He died in 1991, just a few months after taking the stage with McGuinn, Hillman, and David Crosby at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony honoring the Byrds.

![Martin Fabricius Trio - Under the Same Sky (2018) [Hi-Res] Martin Fabricius Trio - Under the Same Sky (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771153226_cover.jpg)

![Seán Mac Erlaine - Music for Empty Ears (2018) [Hi-Res] Seán Mac Erlaine - Music for Empty Ears (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/16/esx5zh4h5a4zqkspzowo3atfu.jpg)