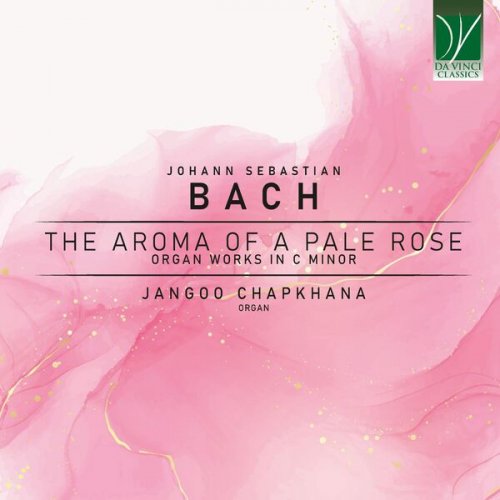

Jangoo Chapkhana - Bach: The Aroma of a Pale Rose, Organ Works in C Minor (2025)

Artist: Jangoo Chapkhana

Title: Bach: The Aroma of a Pale Rose, Organ Works in C Minor

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Organ

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:05:06

Total Size: 342 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Bach: The Aroma of a Pale Rose, Organ Works in C Minor

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Organ

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:05:06

Total Size: 342 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Prelude and Fugue, BWV 546: Prelude

02. Prelude and Fugue, BWV 546: Fugue

03. Prelude (Fantasia) and Fugue, BWV 537: Fantasia

04. Prelude (Fantasia) and Fugue, BWV 537: Fugue

05. Christe, aller Welt Trost, BWV 670

06. Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam, BWV 684

07. Fugue on a theme of Giovanni Maria Bononcini in C Minor, BWV 547b

08. Fugue in C Minor, BWV 575

09. Trio in C Minor, BWV 585

10. Passacaglia in C Minor, BWV 582

During the Baroque and Classical periods, there existed an important underlying concept in composition often referred to as the “key characteristic”. Also known as the “Doctrine of Affections”, this concept carried with it the understanding that certain keys would arouse a specific “affect” – a set of emotions, moods and human feelings.

Working in tandem with key and affect are musical mannerisms, gestures and techniques which contribute to the overall affect of musical utterances. In use in the eighteenth century was a tuning system known as unequal temperament. It was a method of tuning which made some keys sound “out-of-tune” and was also a strong contributing factor to affective descriptions.

Embedded within the musical whole, these were the underlying codes that were understood by well-educated and scholarly listeners.

The term Doctrine of Affections is, in fact, a misnomer because a single agreed-upon canon of affects never existed. Many theoreticians and composers tabled their thoughts on key characteristics, and many were in agreement with the symbolic implication of some keys. At the same time, however, there were notably diverse views on the symbolism of other keys.

Two of the earliest and most important musical figures to codify key characteristics were the composer Jean-Phillippe Rameau (1683-1764) and flautist/composer Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773). Taking things further was the composer/music theorist Johann Mattheson, (1681-1764), who chronicled, in great detail, the affective narratives of no less than seventeen tonalities, notably more than previously documented.

However, one of the most charming portrayals of musical affect comes from amateur flautist and physician Justus Johannes Heinrich Ribock (1743-85), who assigned to the key of C minor “the aroma of a pale rose”.

This key, along with Ribock’s portrayal is the unifying feature in this contrasting programme of organ works by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). It also serves as the illuminant for the (re)interpretations on this recording.

The Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537, was written around 1720 during Bach’s second tenure in Weimar. The Fantasia is in 6/4 time and combines two very distinct sections. The work is truly unique in Bach’s oeuvre – a floating lament with a highly expressive and mournful character. The many suspensions in the writing accentuate the sadness and add a lush quality to the overall affect. The piece ends on the dominant of C minor, thus closing with a question.

The answer comes by way of an energetic fugal subject which contrasts vividly with the tranquillity of the Fantasia. In the middle of the Fugue, Bach introduces a new, chromatic idea which helps propel the music and give it a sense of urgency. As the writing builds in intensity, there is an extended double trill in the manuals over two bars of running quavers in the pedals.

The Trio in C minor, BWV 585, is a delightful arrangement of a two-movement trio sonata by Johann Friederich Fasch (1688-1758). It is one of a number of organ transcriptions of trio sonatas by other composers of the day.

An expressive and highly imitative Adagio is followed by a brisk Allegro, in which, a lively discourse between the two manual parts is underpinned by a strongly-defined bass part. Lasting barely seven minutes in total, the piece provides the player with plenty of opportunities to develop the important art of trio playing at the organ console.

Everything about the solitary Fugue in C minor, BWV 575, suggests that it is an early work. The fugal subject is unlike anything Bach ever penned, with two brief semiquaver flourishes separated by a pause, then followed by a more extended phrase. As the various voices enter, a broken figure is introduced by way of commentary and “filler” during the pauses in the subject. The music is relentless in its character and races around the musical stadium with fast bends and close calls, requiring some nimble fingerwork. The pedal is silent until the very end, when Bach deploys long pedal notes over a quasi-improvisatory section in typical North German style. A brief pedal cadenza and final flourish bring the work to a somewhat abrupt and atypical conclusion.

By way of contrast, the Fugue in C minor on a Theme of Giovanni Maria Bononcini, BWV 547b, is more sober and carefully worked-through with the pedals entering in the exposition and used unremittingly. A counter-subject appears halfway through the work and the two themes are eventually combined. As with the previous Fugue, this work also concludes with an extended fantasy-like coda with rapid manual figurations, exemplifying the North German stylus fantasticus.

Bach’s four-part Clavier-Übung appeared between 1731 and 1741. This monumental offering of music is regarded as being the pinnacle of keyboard composition and stylistic technique and is unequalled in anything published during the eighteenth-century.

The third (and largest) part of the collection was published in 1739 and was written exclusively for the organ. It was Bach’s very first published work for the instrument and represents a powerful demonstration of his skills in organ composition. Oft-titled the “German Organ Mass”, the collection of pieces consists of multiple settings of the German Kyrie and Gloria (BWV 669-677), pairs of settings for each of six Catechism chorales (BWV 678-689) and four Duetti (BWV 802-805). This compelling collection is framed by the colossal Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major (BWV 552/1, BWV 552/2).

The Clavier-Übung is represented by two cantus firmus-style chorales on this recording. Christe, alle Welt Trost (BWV 670) features the cantus firmus in the tenor with three-part-counterpoint woven around the long notes. Unsurprisingly, the maze of counterpoint is always based on the melodic shape of the about-to-appear tenor line. Christ, unser herr, zum Jordan kam (BWV 684) is a work which bubbles over with joy. The text of this Lutheran hymn makes promise of a new life. The blood-tainted waters of the Jordan in which Christ was baptised is represented by relentless semiquavers in the left hand. Cycles of fifths appear throughout the work and the chorale makes its appearance in the pedals. Delicate and packed with Biblical imagery, it is a stunningly-crafted model of its kind.

The Prelude & Fugue in C minor, BWV 546, was not written as a matching pair of pieces. The Fugue was written during Bach’s time at Weimar and the Prelude was composed in Bach’s later years in Leipzig. They were most likely paired by an editor or publisher.

The Prelude is in ritornello form – a formula used by composers whereby a passage or phrase keeps returning. Also an exemplar of musical theology, this form points the listener to the Holy Spirit – the Three in One. A key signature of three flats adds to the theological programme in the writing. Gusts of wind, fanfares and relentless triplets combine in this dramatic and powerful work in which the Holy Trinity appears as a life-affirming force. The surprising C major chord at the end is both majestic and life-affirming. The ensuing Fugue is very much in “stile antico” and cleverly combines a new motif in the middle section with the original theme.

The Passacaglia in C minor, BWV 582 is a towering work in the organ repertory and possibly Bach’s grandest-ever piece for the instrument. Recent research indicates that it was most likely written during his time in Arnstadt, somewhere between 1703 and 1707. The young composer’s experience of listening to the playing of Buxtehude is clearly evidenced in this extraordinary piece.

The passacaglia theme is first heard in the pedals and bears a strong resemblance to a passacaglia by André Raison (1650–1720). It provides the schema for a series of twenty variations, in which, tension and release is an immutable integrant.

The fugue, which follows without a break, is not a separate entity but rather, a substantive part of the Passacaglia, using the first part of the theme as its subject, along with a tenacious countersubject to which Bach added slurs. There are lengthy contrasting episodes for the manuals prior to a re-entry of the passacaglia theme in the pedals, this time in the dominant minor.

This point heralds the start of an intensification which mushrooms out until the music comes to rest on a Neopolitan chord – a veritable thunderbolt chord in the context of this harmonic journey. A long pedal point in the tonic is the only possible denouement. The young master’s final surprise is a tierce de Picardie – a glittering crown which bespeckles the seminal monument.

There was no cut-and-dried formula to the concept of musical affect and no definitive lexicon exists. For, just as emotional DNA is unique to every human, so is our reaction and emotive response to any form of music. Thus, this programme is as much a celebration of human differences as it is an examination of possible connections and emotional threads.

![Black Flower - Abyssinia Afterlife (2014) [Hi-Res] Black Flower - Abyssinia Afterlife (2014) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/anj3jk2va3pc3i9y3pv0m7zde.jpg)