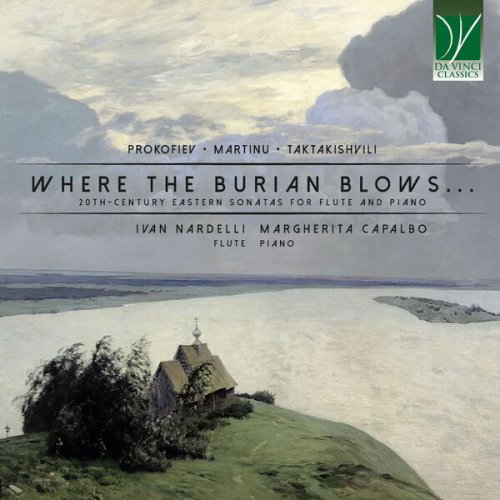

Margherita Capalbo, Ivan Nardelli - Prokofiev, Martinu, Taktakischvili: Where the Burian Blows..., 20th-Century Flute Sonatas (2025)

Artist: Margherita Capalbo, Ivan Nardelli

Title: Prokofiev, Martinu, Taktakischvili: Where the Burian Blows..., 20th-Century Flute Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:45

Total Size: 249 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Prokofiev, Martinu, Taktakischvili: Where the Burian Blows..., 20th-Century Flute Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:45

Total Size: 249 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Flute Sonata in D Major, Op. 94: I. Moderato

02. Flute Sonata in D Major, Op. 94: II. Scherzo

03. Flute Sonata in D Major, Op. 94: III. Andante

04. Flute Sonata in D Major, Op. 94: IV. Allegro con brio

05. Flute Sonata, H. 306: I. Allegro moderato

06. Flute Sonata, H. 306: II. Adagio

07. Flute Sonata, H. 306: III. Allegro poco moderato

08. Sonata: I. Allegro cantabile

09. Sonata: II. Moderato con moto

10. Sonata: III. .Allegro scherzando

The Burian is an icy wind, coming from the steppes of Siberia, and which periodically enters continental Europe bringing storms, cold weather – in a word, a whiff of Siberia into countries normally blessed with a more pleasant climate. The flute, as a “wind” instrument, is animated by breath; and it can be said that the music recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album reveals its Eastern “in-spiration” breathing it into the West.

Of the three composers represented here, Sergey Prokofiev is certainly the best known. Born in today’s Ukraine, he received his first musical training from his mother, who was a Russian pianist. His early musical education took place under the guidance of excellent teachers, such as Reinhold Glière who impressed upon the child his idiosyncratic view of pedagogy and composition, fostering the boy’s spontaneity and avoiding the constraints of traditional academicism. By way of contrast, this approach was the one found by Prokofiev when he was admitted at the Conservatory of St. Petersburg. Even though he could study with some of the leading musicians of the era, he did not feel at ease there. Reports about his difficult relationships with musicians of the standing of Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov are eloquent testimonies of his complex personality.

Prokofiev’s true blossoming coincided with his journeys abroad, in the 1910s, when he visited and remained for some time in Western Europe. His landmark Neoclassicist traits started to emerge on those occasions. The outburst of the Russian Revolution was initially hailed by Prokofiev, although, seemingly, he preferred applauding it from afar than enjoying the new regime firsthand. In any case, he saw that his name and works would be known in his home country, while travelling extensively in America and Western Europe. In 1927 he toured the Soviet Union expansively as a concert pianist; in 1936, he would establish his residency in the USSR together with his wife and children. There, he became a prominent figure in the musical panorama, substantially replacing the star of Dimitri Shostakovich as the leading character in the Soviet stage. Prokofiev was not particularly limited in his interaction with “the Western world”; however, it was his innate prudence which led him to reduce his journeys abroad. He even voiced the “principles” of Soviet music – simple, harmonically traditional, with allusions to, or quotations of, the tunes of Russian folklore. Evidently, however, Prokofiev did not easily adapt to that framework, since his music was much richer than this; still, he also managed to find a good balance, and one which did not compromise the quality of his music.

During World War II, Prokofiev and his wife, Mira Mendelsohn, were evacuated to zones of the USSR where the situation was calmer, including a place in the north of Caucasus, Tbilisi in Georgia, and Alma-Ata, in Kazakhstan. It was during that stay there, in 1943, that Prokofiev composed his Flute Sonata. Back in Russia after the War, Prokofiev – as a good many other composers, with the only exception of the regime’s yes-men – was the object of harsh censorship by the Stalinist regime; he had to make a written apology for his “modernism” and to undergo that humiliation.

The Flute Sonata was the result of a commission by Levon Atovmyan, who represented the Union of Soviet Composers, but was also the assistant to Prokofiev himself. Atovmyan offered part of the budget allotted by the Union of the Composers for commissions in the field of chamber music to Prokofiev, who agreed to write the Sonata. Its composition took him longer than expected, but, in the end, the composer himself affirmed that it was worth the entire sum he was being paid for it. The simple, joyful atmosphere which pervades many passages of this Sonata may be partly due to the influence of the pieces for children on which he was working on at that time. The premiere took place on December 7th, 1943; the pianist was Sviatoslav Richter, Prokofiev’s favourite pianist and the one who premiered many of his solo piano works when Prokofiev’s own piano technique became not wholly adequate for the performance of his own works. A friend of Richter was the flutist of the premiere, i.e. Nikolay Kharkhovsky, who was already well known and would go on to establish himself in prominent roles in the great Russian orchestras. In the same year, Prokofiev cooperated with David Oistrakh, whom he appreciated highly, to adapt this Sonata for violin and piano; the changes regard the flute/violin part (which still is remarkably similar) while the piano part remains unmodified.

From Georgia, where Prokofiev had spent some time during the War, came also Otar Vasilidze Taktakishvili (it was also the home country of Stalin, incidentally: Stalin and Prokofiev died on the very same day).

Taktakishivili’s signature work is precisely his flute Sonata, but this overshadows his many other works, which are lesser known but would deserve greater recognition. He was deeply bound to his homeland, and sought to preserve and to transmit many of its traditional tunes with his music. Similar to Prokofiev, also Taktakishvili received his early musical training from his mother and his extended family. When Prokofiev was writing his Flute Sonata, comparatively close to Tbilisi, Taktakishvili was entering the Conservatory. Short after the beginning of his official training, the budding composer, urged by his mother, entered a competition for the endorsed Anthem of Georgia. He wrote it on the spur of the moment, and then forgot about it, until he discovered that he had won the competition. His career in Georgia and in the USSR was particularly bright; he was the recipient of many State Awards and was elected to important political roles within the framework of the powerful Union of the Composers.

He wrote his Flute Sonata in 1966, and this work, much beloved by both Eastern and Western musicians, is a typical example of his style. There are numerous elements from the so-called “Soviet-realist” palette, including the presence of dances and marches, and, especially, the rejection not only of serialism, but even of the problem it represented.

It is a music deliberately approachable, enjoyable, immediate; it does not craft a new language, as many twentieth-century composers sought to do; it simply enjoys a ready-made tonal structure while tinging it with new shades of his own creation. The composer’s output is fairly neatly divided into two epochs, the first of which is mainly consecrated to instrumental music, and the second to vocal music. The presence of motifs, themes, modes, gestures, and stylistic traits derived from Georgian folklore is also very important in his oeuvre. The “breathing” quality of the flute may have inspired him to infuse this Sonata with themes either directly quoting Georgian sung folklore (building on the “similarity” of flute and singing), or recalling it as a model – for example as concerns rhythm, scales – octatonic passages, use of the Aeolian mode etc.

Closer to Prokofiev’s Sonatas as concerns their years of composition is the (First) Flute Sonata by Bohuslav Martinů. The “First” in parentheses is due to the fact that Martinů actually named it this way, thus hinting at the idea that more were to come. It was to remain the only one, however.

Martinů shares with Prokofiev the openness to experiences abroad; indeed, the two composers were in Western Europe in the same years, which were, incidentally, the unforgettable Roaring Twenties. Similar to Prokofiev, also Martinů began his musical education as a child. But, again similar to him, he did not feel at ease at Conservatory, and therefore he left it in 1910 without graduating. He was deeply engaged in the social and political life of his native Bohemia, but, nevertheless, he moved West, to Paris, for completing his musical education under the guidance of Albert Roussel.

Martinů’s open support for the Czech rebellion against the Nazi regime in his home country earned him the enmity of the invaders, thus preventing him from getting back to Bohemia. However, he wrote several pieces, many of which are very touching, to celebrate, encourage, and foster the rebels’ upholding of a position of freedom. When, however, the Nazis invaded France too, Martinů was forced to flee that country in a very adventurous fashion; later, he was encouraged to leave Europe and to embark for the United States. There he remained for many of his later years, teaching and composing at a hitherto never experienced pace. He taught in such prestigious institutions as the Mannes College of Music and Princeton University. In 1952 he became a naturalized US-citizen; in 1953 he returned to Europe (Western Europe only, of course), and he would die in Switzerland in 1959.

His Flute Sonata was written in 1945, and was composed in the United States, at Cape Cod by New Orleans. The piece was conceived for George Laurent, who was the principal flautist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for nearly 35 years. However, it was not Laurent who premiered it eventually, but rather Lois Schaefer.

In three movements, the piece opens with an expressive and lively movement, an Allegro moderato where melodicism and energy blend harmoniously. The second movement, adagio, is the most touching and intense of the work, allowing for a space of silence within the whirlwind of emotions of the outer movements. The last movement, in fact, closes the Sonata with a brilliant, vivacious, and enthralling outburst of energy.

Together, these three masterpieces of twentieth-century flute literature “breathe” new “air” in the – at times suffocating – world of the modern avant-gardes, and bear witness that it is possible to be modern, and at the same time to remain pleasant in the listeners’ ears.

![Barre Phillips - Three Day Moon (1978/2025) [Hi-Res] Barre Phillips - Three Day Moon (1978/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766322384_cover.jpg)