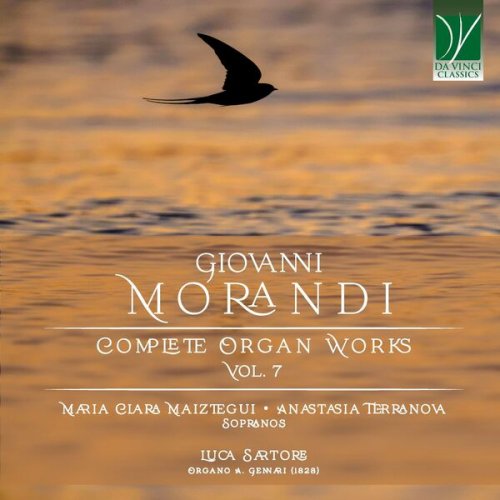

Maria Clara Maiztegui, Anastasia Terranova, Luca Sartore - Giovanni Morandi: Complete Organ Works, Vol. 7 (2025)

Artist: Maria Clara Maiztegui, Anastasia Terranova, Luca Sartore

Title: Giovanni Morandi: Complete Organ Works, Vol. 7

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: lac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:16:44

Total Size: 366 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Giovanni Morandi: Complete Organ Works, Vol. 7

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: lac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:16:44

Total Size: 366 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. In tempore Natalis Domini: No. 1, Sinfonia in Pastorale da eseguirsi nella ricorrenza del Santo Natale

02. In tempore Natalis Domini: No. 2, Hodie Christus natus est – Mottetto a due voci con organo obbligato da eseguirsi nella ricorrenza del Santissimo Natale

03. In tempore Natalis Domini: No. 3, Pastorale da eseguirsi nella ricorrenza del Santissimo Natale

04. In tempore Natalis Domini: No. 4, Tantum Ergo in Pastorale a voce sola con organo obbligato da eseguirsi nella solennità del Santissimo Natale / Paolo Gasparin – Supplementum I

05. In tempore Paschali, Vespro per la Messa del Sabato Santo: No. 1, Alleluia / Laudate Dominum omnes gentes

06. In tempore Paschali, Vespro per la Messa del Sabato Santo: No. 2, Alleluia / Vespere autem sabbati

07. In tempore Paschali, Vespro per la Messa del Sabato Santo: No. 3, Magnificat

08. In honorem Sanctæ Mariæ Magdalenæ: No. 1, Tantum Ergo solenne / Paolo Gasparin – Supplementum II

09. In honorem Sanctæ Mariæ Magdalenæ: No. 2, Marcia Militare ridotta per le feste in onore del cardinal Fabrizio Sceberas Testaferrata

10. In honorem Sanctæ Mariæ Magdalenæ: No. 3, Mulier quæ erat in civitate – Antifona

11. In honorem Sanctæ Mariæ Magdalenæ: No. 4, Ecce ad pedes tuos – Mottetto per la festa di S. Maria Maddalena

The world of the female convents and monasteries is, for most people, a mysterious universe. Some are fascinated by it, others are slightly frightened, some others are strongly prejudiced against it. Few know it directly, and still fewer have a more than cursory experience of what it implies and means.

Influenced by novels or movies with little historical reliability and a penchant for the sensational, many people consider female monasteries as oppressive institutions, where girls were held captive, possibly against their will, and were deprived of the possibility of having a “normal” life. While of course there have been abuses in history – as happens with all other human realities – the general panorama is very different. Several scholars, including numerous musicologists, have explored this (seemingly) hidden and secluded world in the past decades, unveiling a reality which is practically at the other end of the received narrative.

Already in the Middle Ages, female convents were, in most cases, havens of culture and spirituality. Far from constituting isolated hermitages, they mainly were very well connected with the larger society. Nuns were not born with a veil: they had parents and relatives, with whom relationships were maintained. Indeed (and even though this may be slightly questionable from the purely religious viewpoint) many nuns were among the most powerful women of their times. Abbesses, for instance, had an impressive political and social impact, and were responsible for the material, cultural, and spiritual life of numerous inhabitants of the lands under the abbey’s rule.

Furthermore (and more in line with the principles of monastic life), the well-ordered and structured style of a nun’s days was the ideal context in which a woman’s talents could flourish. Married women, at a time when pregnancies were numerous and very dangerous, had normally little or no time for leisure and culture, unless they were queens or princesses. (And, in these cases, the fact of completely outsourcing the education of their children, which was entrusted to nannies and tutors, could in turn be a reason for deep frustration). Nuns, instead, had a daily schedule in which the time left free from prayer and work could be devoted to culture, art, and creativity.

Figures such as that of Hildegard of Bingen are doubtlessly exceptional, and they fascinate countless scholars, believers, and admirers until present-day. But if it was, and is, extremely rare for a person (male or female) to possess all the talents endowed to Hildegard, other figures shine for the brilliancy of their mind and the fecundity of their spiritual and cultural experience. One can mention, for instance, the Helfta nuns, who stand as a shining example of the creativity and intensity of the convent’s life; or, closer to us, the sixteenth-century nuns of St. Vito in Ferrara, Italy. They had created a real orchestra, provided with the full palette of the instruments normally played in a “secular” orchestra of their time. They played in semi-public concerts, which were eagerly attended by the high nobility of Europe. Accounts of their performances, described in colourful awe, bear witness to the listeners’ amazement before the accomplishment and beauty of their art.

In many other Italian cities, such as Milan or Venice, monastic choirs and orchestras elicited similar enthusiasm. Frequently, the nuns sung or played without being seen by the audience; but this aura of mystery only increased the fascination and wonder felt by many. The nuns’ performances were also an integral part of their material survival, since the offerings brought by their admiring listeners were essential for their economy. One could therefore say that music was their “job”, their “work”.

Several monasteries asked for a reduced dowry, or even lifted all requirements, when a candidate for monastic life displayed a remarkable musical talent, or had already a musical education. Numerous daughters of professional musicians could therefore be admitted to monastic life by virtue of their musical accomplishments, without further demands.

And although their nature was different from that of monasteries proper, the Venetian “ospedali” and the Neapolitan conservatories operated according to the same principles. Soon, they became landmarks of the city’s cultural life, and were among the highlights which cultivated and aristocratic visitors had not to miss.

The particularity which fostered the musical life of many female monasteries was that, frequently, the organ was positioned within the area of the church which was reserved for the nuns. The organ, in other words, was “cloistered” just as the nuns. This implied that, according to the monastic rule, male musicians could not access the instrument. The nuns themselves had therefore to provide for their own music. They had to educate younger and musically talented nuns, training them as organists; they had to become autonomous and self-sufficient as concerns their musical life. This was entirely exceptional: whilst female pianists, violinists, or singers were not uncommon in the secular world, female organists were an absolute rarity.

In other cases, the organ could be played by male organists (especially if the instrument was positioned outside the enclosure), but this again led to a fascinating and exceptional situation, i.e. the possibility of a musical interaction between male musicians and consecrated women.

Moreover, it should be added that musicianship, in the convent, was pervasive. Nuns sang the Office, which implied several hours of sung liturgy every day; furthermore, they frequently made music as a form of spiritual recreation; and, in some convents, they also played and performed in what we would today describe as “public concerts”.

Finally, it has to be remembered that female composers were much more common within the walls of the cloister than outside them. At times, it was a need – the necessity for a religious community to provide for its own services, keeping into account the gifts and the limitations of the convent’s musicians. At times, it was a choice: the possibility of enriching the worship with something created by the nuns and for the nuns, specifically tailored upon the talents and the weaknesses of the local musicians.

It is within this framework that the works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album should be understood and studied.

Giovanni Morandi, whose complete works for the organ are being published by Da Vinci in a multi-year project, is one of the most important figures as concerns Italian organ music in the nineteenth century. His adult life is neatly divided into two distinct periods: the first as a married man, the second as a widower. As the husband of a famous opera singer, Morandi journeyed throughout Europe with his wife, befriending many of the most important musicians of his time (including Rossini). Morandi himself played, performed, and taught at an international level, thus acquiring lasting fame and expertise.

After his wife’s untimely death, Morandi changed his lifestyle completely. He settled in Senigallia, a beautiful but relatively small city on the Adriatic coast of the Marche region in Italy. He virtually never left the city, leading a sober – nearly monastic! – life in turn. However, just as living in a monastery did not prevent nuns from being protagonists of the cultural and social life of their times, similarly Morandi’s seeming seclusion was only a superficial impression. He was very active at all levels of his city’s life – as a composer, performer, teacher, manager, and even as a politician – and he played the organ at many ecclesiastical institutions. These included the Poor Clares’ convent of St Mary Magdalene in Serra de’ Conti.

In comparison with other religious orders, the Poor Clares tended to dedicate less time and energy to music, in compliance with their primary vocation to poverty and sobriety. Nevertheless, they also believed that poverty was to be pursued in their own daily life, but that the God they worshipped deserved all the beauty they could provide in their liturgies. For this reason, they employed a famous and brilliant organist such as Morandi, who not only played for them regularly, but also composed some beautiful works expressly for their liturgy.

The works for Christmastide (a period of the liturgical year characterized by great solemnity and, at the same time, profound tenderness) are perfect examples of his creativity. They feature a “Pastoral Symphony” and two other “Pastorales”: this is a genre frequently found in Christmas music, evoking the timbre and style of the shepherds’ music. It alludes, of course, to their adoration of the Child Jesus. There are also two works for solo singers with organ; one of them is a motet, setting the lyrics of one of the most beloved Christmas texts, while the other is another Pastorale on the words of a Eucharistic hymn. This underlines the tight connection between the adoration of the Holy Sacrament (the Body of Christ) and that of the Incarnate Word, the Child Jesus.

Before the Second Vatican Council, the joy of Easter – the most important solemnity of the liturgical year – was anticipated to the Saturday before Easter Sunday; therefore, the Vesperal music for Holy Saturday was already entirely festive. The joyful mood of the works recorded here may therefore puzzle contemporary listeners, but it has to be understood within the framework of earlier liturgical habits and patterns.

Finally, there is the music composed in honour of St Mary Magdalene, the patron saint of the convent. This is possibly the most original of all works recorded here: Christmas and Easter music could in principle be “recycled” on other occasions outside the convent, but the works for the convent’s feast-day were conceived for it, and for it only. Here again we have a Tantum ergo: St Clare, the founder of the Poor Clares, was famous for her Eucharistic devotion. An antiphon and a motet conceived for the nuns’ voices celebrate the importance of Mary Magdalene for the entire Church. But the most curious piece of all is the Military March included here: although Morandi (different from his contemporaries) eschewed the contamination between sacred and operatic music, still the festive occasion prompted a greater flexibility, and the possibility, for the nuns’ ears, to enjoy a rather secular kind of music. And this is yet another instantiation of the freedom and creativity of female monasteries.

![Lighthouse - One Fine Morning (Anniversary Edition) (2025) [Hi-Res] Lighthouse - One Fine Morning (Anniversary Edition) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-11/1762501996_cnexzgptjdagb_600.jpg)