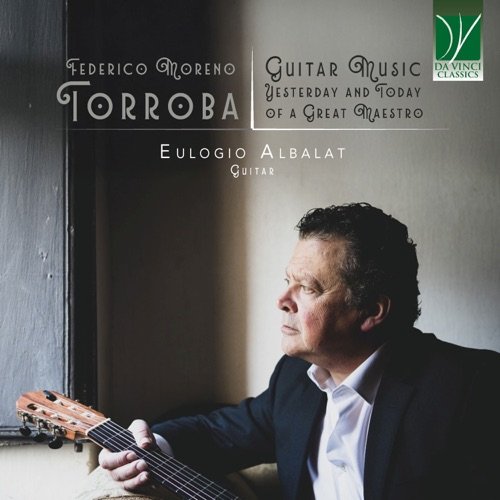

Eulogio Albalat - Federico Moreno Torroba: Guitar Music, Yesterday and Today of a Great Maestro (2025) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Eulogio Albalat

Title: Federico Moreno Torroba: Guitar Music, Yesterday and Today of a Great Maestro

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Publishing

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / alac 24bits - 48.0/96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:16:15

Total Size: 284 / 882 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Federico Moreno Torroba: Guitar Music, Yesterday and Today of a Great Maestro

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Publishing

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / alac 24bits - 48.0/96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:16:15

Total Size: 284 / 882 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 1, Turégano

02. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 2, Torija

03. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 3, Manzanares el Real

04. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 4, Montemayor

05. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 5, Alcañiz

06. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 6, Sigüenza

07. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 7, Alba de Tormes

08. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 8, Alcázar de Segovia

09. Castillos de España, Vol. 1: No. 9, Burgalesa

10. Suite Castellana: No. 1, Fandanguillo

11. Suite Castellana: No. 2, Arada

12. Suite Castellana: No. 3, Danza

13. Nocturno

14. Aires de la Mancha: No. 1, Jeringonza

15. Aires de la Mancha: No. 2, Ya llega el invierno

16. Aires de la Mancha: No. 3, Coplilla

17. Aires de la Mancha: No. 4, La Pastora

18. Aires de la Mancha: No. 5, La Seguidilla

19. Madroños

20. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 1, Olite

21. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 2, Zafra

22. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 3, Redaba

23. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 4, Javier

24. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 5, Simancas

25. Castillos de España, Vol. 2: No. 6, Calatrava

26. Sonatina: I. Allegretto

27. Sonatina: II. Andante

28. Sonatina: III. Allegro

It may seem untimely, or even inappropriate in our present times, to record a monographic album devoted to Maestro Federico Moreno Torroba (Madrid, March 3, 1891 – Madrid, September 12, 1982). Yet, from my point of view, this act of personal devotion toward the Madrid-born composer takes on greater significance than ever.

Much has been written, though not from the perspective of pragmatic or purely musical analysis, but rather through another lens, one employing predominantly musicological yardsticks. The result of such approaches, however, falls far short of illuminating Torroba’s absolute compositional mastery. Guitarists, for the most part, are not inclined to analyze the scores of our instrument in a way that remains impartial to the era of their creation. By way of example, one may cite Barrios Mangoré, who has often been compared idiomatically to F. Chopin, although he was born a century later.

Torroba’s case, however, is altogether different. His music transcends barriers through the extraordinary melodic strength of his writing, which, when joined with a rhythmic wisdom of rare distinction, renders his art truly unrepeatable. It becomes evident that other parameters must be considered more suitable when studying the works of great guitarists and composers: the adaptation of the works to the guitar’s technique, their timeless melodic wealth, the rhythmic development of the piece itself, and, in general, the compositional richness of the work as experienced in performance—and, above all, the impact upon the listener during a concert, which remains the surest of all measures. Musicological connotations, by contrast, ought to be kept at the margins of the musical act itself.

To recount anecdotes and biographical details about the Maestro would be of little relevance, since these are readily available in numerous digital sources, though less so in printed form. Instead, I will comment upon my personal contact with his music, and the reasons behind my interpretation.

Federico Moreno Torroba composed the works included in this CD between 1920 and 1978—some, therefore, more than a century old, and others, more recent, only half that age. I emphasize this because the manner in which this music is performed today, in my view, often breaks with the interpretive and musical canons of the time in which it was conceived. The greatest guitarist of international stature in that era to first perform music Torroba had composed specifically for him was Andrés Segovia, beginning with his Danza of 1920. Without fear of error, I would assert that Segovia knew Torroba’s music better than anyone. He did not exaggerate tempi; he sought instead a sound of paradigmatic richness and, most importantly, he knew how to endow each note with its precise weight and intention, managing to attend both to the particular and the general simultaneously.

Apart from his talent and genius, such an approach to music is today difficult to find, perhaps because of the unfortunate interpretative fashion imposed by competitions for guitar—and for other instruments—that has become the norm: faster and higher! One could also speak at length here about the strings Segovia used and those employed today on the vast majority of guitars.

On the other hand, the works that function best on the guitar are those Segovia himself edited and fingered. As an example, one may cite Castillos de España, Vol. 1, in which Jim Ferguson’s extraordinary edition has recovered every detail and fingering Segovia employed. The second volume of Castillos de España, notwithstanding its great idiomatic and musical richness, cannot be approached with the same freedom of technical or expressive means as the first. One need only consider the tremolo of Simancas and Zafra, where the guitarist must constantly employ a right-hand alternation not in accordance with the traditional tremolo technique.

For the reasons already cited, the music composed between 1920 and 1966—all of it fingered by Segovia—achieves such fluency of execution that it allows for an unquestionable degree of musical flow. Thus, on one hand, we have Suite Castellana, Sonatina, Nocturno, or Burgalesa; and on the other, Aires de la Mancha of 1966. In this latter case, the edition bears no name, and much less any fingering indications: the score is bare, and guitarists must labor greatly to bring the five pieces to life, their apparent compositional simplicity concealing the difficulties of execution.

Returning to the Burgalesa, it should be noted that Andrés Segovia dictated it to my first teacher, Don José Sanluis Rey, during the International Music Courses in Compostela in 1959. That score, with Segovia’s own fingerings and indications, is the one I have chosen for my performance of the piece.

Here arises the question: should one listen to the judgment of musicologists, or decide instead what is most useful for the guitarist? Should we follow the scores exactly as composed—such as the unpublished originals of Villa-Lobos, Manuel María Ponce Cuéllar, or Federico Moreno Torroba—or, on the contrary, should we perform the editions of great guitarists who, in direct contact with the composers and through multiple discussions and collaborations, determined together what was and was not feasible on the guitar, thus arriving at consensuses that would ultimately serve the instrument coherently? It must be remembered that, of the composers mentioned (with the exception of Villa-Lobos), none played the guitar, nor knew it with precision. After many years in service to the six-stringed instrument, I lean decidedly toward the latter view. I too have had the opportunity to discuss and work directly with composers, and have always reached fruitful conclusions with the scores entrusted to me—whether for performance in concert or for formal recordings—and invariably arrived at common ground with the composers themselves.

Regarding my interpretation of this music, I have sought inspiration from the musical legacy instilled in me by my family over the years. They were accomplished pianists, including my parents and my maternal grandmother, María Lois. She knew Isaac Albéniz and was personally acquainted with Enrique Granados and Enrique Fernández Arbós, among others. All this pianistic influence has enabled me to play the guitar differently—not better nor worse, but distinctly. I have always listened to how great composers’ works were interpreted on the piano, and these hearings have inevitably instilled in me a different interpretive spirit, as though the guitar were a larger and more harmonic instrument, always striving for the greatest possible legato, except where the composer indicates otherwise. I also employed a special right-hand technique that allowed me to bring out those inner voices so characteristic of Torroba.

Velocity has never been my concern; rather, the unyielding principle of not letting a single note pass without its full musical—not merely metric—value, striving to endow each with its meaning and undeniable reason for being.

I have also considered the music that served as inspiration for Torroba. For instance, observe bars 28 to 32 of Alcázar de Segovia, where one senses the influence of the Norman composer Erik Satie and the Impressionists. Such a moment—a pause in time, as though a reminiscence of the past—becomes an interpretive gesture, a backward glance evoking the timelessness that music can attain.

As for the recording, I made it at my country home, with electronic equipment designed and built entirely by myself, thanks to my studies in the electronics of sound. I chose the sonority I prefer: very direct, with great presence, while attempting to avoid excessive noise from the nails upon the strings. In this respect I have always favored direct takes, even if they occasionally capture a minor extraneous sound. This type of sound demands considerable control of the right hand, but the result is more authentic than other, more distant and filtered recordings.

A guitar must always sound like a guitar.

![The Messthetics & James Brandon Lewis - Deface The Currency (2026) [Hi-Res] The Messthetics & James Brandon Lewis - Deface The Currency (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771424652_1.jpg)

![Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res] Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771663366_nhs500.jpg)

![Danakil Safari - From the Soil (2026) [Hi-Res] Danakil Safari - From the Soil (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771561850_h6jyygzrq1lpb_600.jpg)