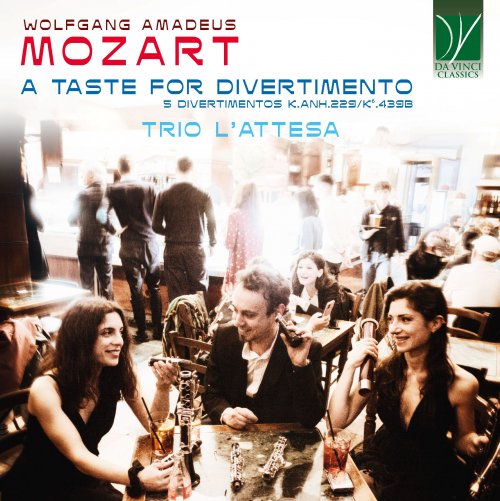

Trio l'Attesa - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: A Taste for Divertimento, 5 Divertimentos K.Anh.229/K6.439b (2025)

Artist: Trio l'Attesa

Title: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: A Taste for Divertimento, 5 Divertimentos K.Anh.229/K6.439b

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Publishing

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:17:06

Total Size: 348 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: A Taste for Divertimento, 5 Divertimentos K.Anh.229/K6.439b

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Publishing

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:17:06

Total Size: 348 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Divertimento No. 1 in C Major: No. 1, Allegro

02. Divertimento No. 1 in C Major: No. 2, Menuetto. Allegretto

03. Divertimento No. 1 in C Major: No. 3, Adagio

04. Divertimento No. 1 in C Major: No. 4, Menuetto

05. Divertimento No. 1 in C Major: No. 5, Rondo Allegro

06. Divertimento No. 2 in C Major: No. 1, Allegro

07. Divertimento No. 2 in C Major: No. 2, Menuetto

08. Divertimento No. 2 in C Major: No. 3, Larghetto

09. Divertimento No. 2 in C Major: No. 4, Menuetto

10. Divertimento No. 2 in C Major: No. 5, Rondo

11. Divertimento No. 3 in C Major: No. 1, Allegro

12. Divertimento No. 3 in C Minor: No. 2, Menuetto

13. Divertimento No. 3 in C Major: No. 3, Adagio

14. Divertimento No. 3 in C Major: No. 4, Menuetto

15. Divertimento No. 3 in C Major: No. 5, Rondo Allegro assai

16. Divertimento No. 4 in C Major: No. 1, Allegro

17. Divertimento No. 4 in C Major: No. 2, Larghetto

18. Divertimento No. 4 in C Major: No. 3, Menuetto

19. Divertimento No. 4 in C Major: No. 4, Adagio

20. Divertimento No. 4 in C Major: No. 5, Allegretto

21. Divertimento No. 5 in C Major: No. 1, Adagio

22. Divertimento No. 5 in C Major: No. 2, Menuetto

23. Divertimento No. 5 in C Major: No. 3, Adagio

24. Divertimento No. 5 in C Major: No. 4, Romance Andante

25. Divertimento No. 5 in C Major: No. 5, Polonaise

In the mid-1780s, Vienna’s twilight hours often resounded with the elegant conviviality of Mozart’s chamber music. One can easily envision Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – newly settled in Vienna, revelling in the city’s vibrant musical life – gathering with a few close friends in a candlelit room. In such an intimate milieu Mozart’s Divertimenti K. 439b were likely born, not as grand public commissions but as private pleasures. These five Divertimenti, comprising twenty-five miniature movements in total, were originally composed for three basset horns – an unusual ensemble of alto clarinets whose mellow timbre Mozart grew to love – during a period of intense creativity, around 1783. The first publication dates 1803 by Breitkopf & Härtel with the title Petites pieces pour deux Cors de Bassette et Bassoon and includes only movements from the second Divertimento. In the following years several editions appeared with different instrumentations: two violins and cello; fortepiano; two clarinets and bassoon. Mozart’s fascination with the basset horn had begun only a few years prior, when he first featured its dusky voice in his magnificent Serenade K. 361 and soon after in the solemn strains of his Maurerische Trauermusik K. 477 – Masonic funeral music. The basset horn special character – by turns gently melancholic and eerily sonorous – became associated with Masonic ritual, a connection not lost on Mozart, who joined the Freemasons in 1784. Yet in these Divertimenti, that same instrument sheds its funerary gravity and speaks in bright, untroubled tones, perfectly suited to an evening of refined amusement. Mozart’s decision to write for three equal wind voices was as practical as it was inspired. The Stadler brothers (Anton and Johann), virtuosi on clarinet and basset horn, were in Mozart’s circle at this time; their presence no doubt sparked the composer’s interest. Mozart, ever the experimenter, was reportedly open to adapting the instrumentation during these informal sessions. In the end he settled on the sonorous blend of three basset horns, finding in their unified tone a unique warmth and intimacy. From Mozart’s pen flowed music that, while scaled for a few friends rather than a full orchestra, loses none of the craftsmanship and charm that grace his larger works. The word divertimento implies being amused, yet in Mozart’s hands such music transcends the idea of background entertainment. These are not careless trifles, but exquisitely balanced pieces that transform modest occasions into art. The genre had roots in serenades and cassations, written to accompany outdoor festivities or noble gatherings, but Mozart infused it with his own imagination. Each of the five Divertimenti follows a five-movement plan, usually beginning with a lively Allegro, followed by minuets, lyrical slow movements, and ending with a finale that sparkles with life. This sequence offers contrast, variety, and balance, as if Mozart were curating a musical banquet where each course refreshes the palate in turn. What might have been ephemeral music becomes, through his genius, something enduring and endlessly rewarding.

The first of the set opens with an Allegro that seems to embody daylight itself, a buoyant and gracious theme introduced with natural ease. The three instruments converse with one another like companions at table, exchanging phrases, imitating one another, weaving harmonies that are transparent yet full. The ensuing minuet carries an air of refinement, its poised rhythm suggesting the steps of dancers moving in candlelit halls. At the centre lies an Adagio, tender and unhurried, where melody sings with the simplicity of an aria. Another minuet restores the festive tone, before the work concludes with a rondo whose recurring theme invites both familiarity and surprise. This balance of dance, song, and play is the template Mozart adapts and enriches across the series.

The second Divertimento mirrors the first in structure, but here Mozart deepens the lyrical character. Its opening Allegro seems to burst forth with confidence, but the slow movement is more inward, its lines carrying a shade of melancholy as if Mozart were allowing private reflection amidst public conviviality. The minuets are elegantly proportioned, their trios offering contrast with excursions into distant keys. The final Rondo is quick and light, filled with the kind of rhythmic wit that Mozart loved, phrases that stop short or dart off unexpectedly, eliciting a smile from the listener. There is in this work a certain grace of proportion that reminds us how instinctively Mozart could balance variety with coherence.

The third of the set contains perhaps the most dazzling finale, an Allegro assai whose rondo theme scampers with irresistible verve. Before that comes a finely wrought Adagio that, though brief, is suffused with warmth, its melody unfolding with vocal grace. Mozart was always a dramatist, and even here, in a work for a small wind ensemble, he writes as though for characters on a stage: voices interact, complement, challenge, and reconcile. The structure is simple, yet the interplay creates a sense of dialogue and narrative. In these movements one may hear an echo of Mozart’s operatic instinct, for he cannot help but endow each line with a sense of personality.

With the fourth Divertimento Mozart begins to reshape the pattern. After an opening Allegro, he introduces a Larghetto, serene and luminous, its songlike line supported by delicate harmony. Only then comes a minuet, leading to another slow movement, this time an Adagio of particularly touching character. By doubling the number of slow movements and reducing the dances, Mozart creates a different balance, one that invites the listener deeper into contemplation. The finale, marked Allegretto, brings a smile back, gentle rather than exuberant, like conversation winding down at the close of an evening, graceful and unforced. The entire Divertimento feels more inward, as if Mozart wanted to prove that even a genre intended for light entertainment could bear moments of profound intimacy.

The final Divertimento of the set departs most boldly from convention. Instead of the expected lively beginning, it opens with an Adagio, solemn yet tender, casting a spell of stillness before any dancing begins. Here Mozart turns the genre on its head, beginning not with festivity but with reflection. The subsequent minuet restores motion, but again the centre of gravity lies in the slow movements. A second Adagio and a Romance, marked Andante, whose title alone suggests intimacy and lyric warmth. The conclusion is a Polonaise, a dance of stately character and gentle exoticism, which crowns the series with a gesture both dignified and fresh. The sequence of movements in this fifth Divertimento demonstrates Mozart’s instinct for variety and invention, never content to repeat a formula but always shaping the material to offer something new. The presence of a Romance and a Polonaise reminds us of Mozart’s openness to influences from popular and courtly traditions alike, binding cosmopolitan elegance with heartfelt song.

Mozart’s capability to invest such modest works with depth is even more remarkable when we recall that these pieces were composed during a period of intense creative output. Around the same years he was writing concertos that transformed the genre and operas that would define his legacy. Yet in these smaller forms he found another channel for his imagination, allowing him to explore the expressive possibilities of instrumental colour and the art of crafting movements that, though brief, feel complete. They reveal his ability to shift seamlessly between public grandeur and private charm, to write music that could both entertain and move. If his concertos astonished audiences with brilliance and his operas captivated with drama, these divertimenti whisper another truth: that the greatest artistry can also appear in miniature. Though written for humble occasions, these divertimenti carry within them the broader cultural world of Mozart’s Vienna. This was the era of the Enlightenment in music, when art sought to delight and uplift simultaneously. We hear in K.439b the ethos of Mozart’s age: the belief that beauty and simplicity need not be trivial, and that pleasure and artistry can walk hand in hand. Contemporary Viennese society adored such tuneful, expertly crafted pieces – they were the musical decor of daily life for the well-to-do. One can imagine these very Divertimenti being played at an aristocratic family’s summer estate, the gentle sound of basset horns wafting through open French doors into an evening garden. The cultural crosscurrents of refined classicism and learned taste meet in these works: while easily enjoyed by any casual listener for their melody and charm, they also contain subtle nods to Mozart’s erudition. A flicker of counterpoint in an inner voice, a hint of Baroque-style sequence in a development section, or a miniature fanfare – such elements would quietly please the cognoscenti without disturbing the piece’s genial surface. Mozart was a master at embedding sophistication within apparent simplicity.