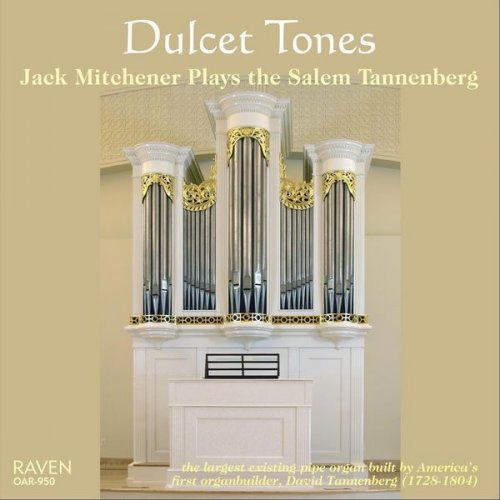

Artist:

Jack Mitchener

Title:

Dulcet Tones

Year Of Release:

2009

Label:

Raven

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 1:15:54

Total Size: 362 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:1. Jack Mitchener – Toccata in D Minor (04:02)

2. Jack Mitchener – Canzona quarta: La pace (02:17)

3. Jack Mitchener – Il secondo libro di Toccate: Toccata I (03:59)

4. Jack Mitchener – Ciacona in F Minor (07:56)

5. Jack Mitchener – Pastorale in F, BWV 590: I. — (02:27)

6. Jack Mitchener – Pastorale in F, BWV 590: II. — (03:22)

7. Jack Mitchener – Pastorale in F, BWV 590: III. — (03:14)

8. Jack Mitchener – Pastorale in F, BWV 590: IV. — (04:55)

9. Jack Mitchener – Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele (03:14)

10. Jack Mitchener – Wer nur den lieben Gott (02:22)

11. Jack Mitchener – Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 730 (01:44)

12. Jack Mitchener – Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 731 (02:29)

13. Jack Mitchener – Sonata in D, WQ 70, No. 5: Allegro di molto (07:34)

14. Jack Mitchener – Sonata in D, WQ 70, No. 5: Adagio e mesto (03:31)

15. Jack Mitchener – Sonata in D, WQ 70, No. 5: Allegro (05:48)

16. Jack Mitchener – Flötenuhrstücke, Hob. XIX: 15: Allegro (01:31)

17. Jack Mitchener – Flötenuhrstücke, Hob. XIX: 10: Andante (01:03)

18. Jack Mitchener – Flötenuhrstücke, Hob. XIX: 9: Menuetto (00:53)

19. Jack Mitchener – Flötenuhrstücke, Hob. XIX: 24: Presto (01:02)

20. Jack Mitchener – Concerto in G Minor: I. (Allegro) (04:49)

21. Jack Mitchener – Concerto in G Minor: II. Adagio (03:19)

22. Jack Mitchener – Concerto in G Minor: III. Allegro (04:12)

In charting the emergence of the Baroque style around 1600, the powerful verbalism of monody and operatic recitative seems often to eclipse other elements. However, the rise of independent and idiomatic instrumental genres also helps demarcate the major shift in style. The seventeenth-century toccata, with roots in earlier, preludial playing on both keyboard and lutes, reinforces its idiomatic language with extensive use of florid passage work, a reminder of the genre’s nature as a “touch piece” (from the Italian toccare: to touch). Moreover, the often sectional nature of the early-Baroque toccata allowed it to become both expansive and more explicitly formal.

Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1710), a fixture in Roman musical circles from the middle of the century, enjoyed the patronage of Queen Christina of Sweden and the Ottoboni and Borghese families, and performed in the company of musicians like the violin virtuoso, Arcangelo Corelli. Pasquini’s d-minor toccata is a sectional work in which the use of pedal points in both the opening and closing sections provide a satisfying degree of symmetry. The diverse treatments of florid passage work, counterpoint, and motivic display add both architectural clarity and variety to the work as a whole. Pasquini’s generation in Rome was strongly influenced by Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), the organist of the Giulian Chapel at the Vatican, and in that position one of the most formidable leaders of the Roman musical establishment. His approach to the playing of toccatas advocated a rhetorical flexibility, likening them to the madrigals, as though perhaps they had a silent text to guide the expression. He writes in his Il secondo libro di Toccate . . . :

"This kind of playing, just as in modern madrigal practice, should not stress the beat. Although these madrigals are difficult, they will be made easier by taking the beat sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, or even pausing, depending on the expression or the sense of the words." Additionally, in the dedication to this collection, he singles out the qualities of grace, facility, variety of measure, and loveliness as necessary for the “new manner.” Inviting these qualities, his Toccata 1 from this collection opens with ornamental passage work, followed by dynamic flights of fancy that alternate with brief moments of expressive repose.

Significantly, some early instrumental forms, even where the language was idiomatically instrumental, maintained formal ties to vocal music, as in the canzona. Giovanni Paolo Cima (c. 1570- 1630), a prominent Milanese composer and pioneer in establishing the prominence of trio texture, offers a typical model in his Canzona Quarta: la Pace. The opening duple-meter section proclaims its vocal song heritage with the signature dactylic motto, while subsequent sections alternate dance-like, triple-meter writing with more richly textured duple-meter passages.

The German organ tradition in the Baroque era is famously and extensively represented by the music of J. S. Bach (1685-1750), who, as a culminating figure, was significantly influenced by earlier composers like Dieterich Buxtehude (c.1637-1707) and Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706), both of whose works he would have known from collections like the so-called “Andreas Bach Buch,” an anthology compiled by Sebastian’s older brother, Johann Christoph. Pachelbel, organist at St. Sebald’s Church in Nuremberg, composed six ciaccone, continuous variations on a ground bass that become important antecedents of works like Bach’s Passacaglia in c minor. Pachelbel’s Ciacona in f, like many sibling works, is based on a falling tetrachord ostinato, generally present, though sometimes imbedded in a more figural line.

Bach’s Pastorale in F, BWV 590, is something of an unusual composite of movements, and questions of its coherence and genesis remain unresolved. The first movement is the programmatic “pastorale,” whose flat-key signature, pedal points, and compound meter were typical attributes of shepherd music in eighteenth-century evocations, often with overtones of piffari playing at Christmas time. The other three movements are familiar in suite and sonata configurations: the second movement offers a binary construction reminiscent of the allemande, while the third movement presents a languorous ornamental line over a steadily pulsing accompaniment; the fourth movement, a binary gigue, brings the whole to a sprightly conclusion.

The chorale prelude was naturally a critical form for Lutheran organists, and Bach’s approach to the genre was generally text-based, seeking to render the specific affect of the chorale poetry or to paint individual words in sound. This verbalism aside, it is striking how wide ranging his approach to the chorale prelude was, with extended contrapuntal fantasias at one end of the scale and intimate, miniature settings at the other. The two settings of “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier,” a chorale sung in preparation for hearing the sermon of the day, are both small-scale jewels, without counterpoint or interludes between the chorale phrases, and in their dimensions akin to the chorales of the Orgelbuchlein. BWV 730 features rich harmony, including chromatic inflection and expressive use of the major ninth, and despite its brevity, has a remarkable fullness with its five-voice texture. BWV 731 adopts a pronounced decorative style, the sweetness of which seems to echo the chorale’s reference to the “sweet teachings of heaven.”

Bach’s pupils, unsurprisingly, were steeped in his approach to the chorale. Gottfried August Homilius (1714-1785) came to Leipzig as a law student at the university in 1735, but his legal studies were in counterpoint with music studies under Bach’s direction. Like his teacher, he later became a Kantor, appointed in Dresden in 1755, and also wrote a full yearly cycle of church cantatas. His chorale preludes on the communion hymn, “Schmücke dich” and “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten” are both trio settings with the cantus firmus freely unfolding in one of the two treble voices.

Bach’s pedagogical influence embraced not only his students at Leipzig, but the ranks of his family, as well. In his famous keyboard treatise, Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, C. P. E. Bach (1714-1788), Sebastian’s second surviving son, reiterated the importance of hearing worthy models. He writes that “in order to arrive at an understanding of the true content and affect of a piece, and, in the absence of indications, to decide on the correct manner of performance . . . , it is advisable that every opportunity be seized to listen to soloists and ensembles.” Later he adds that “as a means of learning the essentials of good performance, it is advisable to listen to accomplished musicians.” No doubt the fabled playing of his father was oftentimes the son’s close-at-hand example. Ironically then, C. P. E. Bach as organist and organ composer did not continue the contrapuntal prowess of his father—it would have proved decidedly old fashioned in the age of galanterie—nor did he make use of the pedals in an extensive way, a reversal of the technique his father had done so much to establish and extend. Several years after his father’s death, tellingly around the time he was applying for his father’s Leipzig post for the second time, C. P. E. Bach composed four organ sonatas, W70/3-6, and they clearly reflect the change of taste and style encouraged at Frederick the Great’s court, where Bach was in service. His Sonata in D, W70/5, favors vivid contrasts—the contrasts of dynamics and also the contrast of thin textures with bold chords—and the graceful language of glistening arpeggios and light figuration.

Bach’s colleagues at the Prussian court included both Carl Heinrich Graun (1703-4-1759) and his older brother, Johann Gottlieb (1702-3-1771). Attributions to one sibling or the other have sometimes proved problematic, as is the case with the Concerto in g. A 1992 edition (Zwicky) attributes the work to Carl Heinrich; a 1999 edition (Franke), on the other hand, cites Johann Gottlieb as the composer. The work hearkens back to Bach and Vivaldi rather than looks ahead to more classical tastes. In part, the very notion of concertos for unaccompanied organ recalls Bach’s successful transcriptions of Italian concertos at Weimar, in which the organ is cast in the dual roles of both orchestra and soloist. In Graun’s concerto, the language and forms are also decidedly Baroque. The first movement’s ritornello is signaled by its opening three “hammerstrokes,” a familiar idiom of Italian concertos, and the development of motivic material takes the form of Fortspinnung, a developmental “spinning out” of material that gives the Baroque concerto its characteristic energy. The third-movement ritornello in its large leaps and reiterated notes additionally recalls the allegro style of Vivaldi.

Haydn’s Flötenuhrstücke occupy a special niche as works for musical clocks: in this case clocks with mechanical organs of flute pipes activated by a pinned cylinder. Prince Esterházy’s librarian, Pater Primitivus Niemecz, made several of these towards the end of the eighteenth century, including at least one for Esterházy (1793). Unsurprisingly, this clock featured the music of the court composer, Haydn. Performed non-mechanically as organ solos, the pieces extend the organist’s repertory of late eighteenth-century music with engaging examples of dance music, sprightly figuration, and elegant turns.

![Susie Philipsen - Sunday Kissing Club (2026) [Hi-Res] Susie Philipsen - Sunday Kissing Club (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771738386_500x500.jpg)

![Gonzalo Mazzutti - Lo que nos une (2026) [Hi-Res] Gonzalo Mazzutti - Lo que nos une (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771563491_cover.jpg)

![Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res] Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771663366_nhs500.jpg)