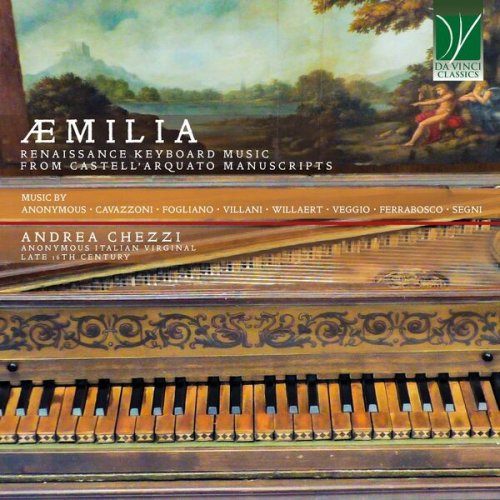

Andrea Chezzi - Æmilia - renaissance keyboard music from castell'arquato manuscripts (2026) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Andrea Chezzi

Title: Æmilia - renaissance keyboard music from castell'arquato manuscripts

Year Of Release: 2026

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:01:47

Total Size: 405 mb / 1.31 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Æmilia - renaissance keyboard music from castell'arquato manuscripts

Year Of Release: 2026

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:01:47

Total Size: 405 mb / 1.31 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Ricercada de marcantonio in bologna

02. Pavana - Saltarello de la pavana - La coda I

03. Ricercada

04. Pavana - Saltarello de la pavana - La coda II

05. Ricerchare

06. Ricerchada

07. Pavana - Saltarello de la pavana - Riprese

08. La Delfina

09. Gazollo

10. Il puliselo

11. La moretta

12. Il cramoneso

13. Zorzo I

14. Ricercada Vil

15. O gloriosa domina

16. La fugitiva Claudius a. 4

17. Il carmoneso

18. Pavana de la bataglia - Il saltarello de la bataglia - La tedeschina

19. Ricercare

20. Io mi son giovineta

21. Ricercada II

22. Pavana in su la chiave di b fa be mi - Saltarello de la pavana - Ripresa

23. Il caselle

24. Il milaneso

25. Ciel turchin

26. La pose borela

27. Recercada per b mollo del primo tono

28. Pavana - Saltarello de la pavana - la coda III

29. Zorzo II

30. Non ti partir da me

31. Al milanese

32. Liciolo

33. Ricerchare per musica ficta

The archive of the Chiesa Collegiata di Castell’Arquato (Piacenza), in Emilia, preserves within it an important musical fonds, consisting of manuscript and printed music dating chiefly from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This collection affords us a view of the activity of a small Po Valley chapel of that period.

In several fascicles there survives a series of intabulations for keyboard instrument, written by different copyists over a span ranging from the first half of the sixteenth century to the early decades of the next. The assembled pieces are of various types: dances, works of a religious character, ricercars, transcriptions.

The keyboard instruments for which these pieces are intended are the organ—principally for works of a sacred character—and the harpsichord (or the virginal), preferred for the dances, while the transcriptions and ricercars can be adapted to both instruments. The instrument used for the present recording is an Italian virginal dating from the late sixteenth century. An anthological selection of pieces contained in the Castell’Arquato collection has been made in order to enhance this rare historical specimen with the most suitable pages and to offer an overall survey of the various musical forms present in the manuscripts. The use of early fingerings has served to render more unified and coherent the choices relating to phrasing, articulation and agogic shaping, in a body of compositions as variegated as that presented here. It was decided not to include pieces specifically intended for the liturgy of the Mass, which are more suited to performance on the organ.

The identifiable composers for some of the works recorded here are organists and maestri di cappella of Emilian origin who were esteemed in the most important Italian musical centres: the Bolognese Marco Antonio Cavazzoni; the Modenese Jacopo da Fogliano and his pupil Giulio Segni; the Piacentines Claudio Maria Veggio and Giuseppe Villani. To these authors we owe above all the ricercars, a form considered more worthy of an authorial reference than the dances, which in this manuscript are anonymous. As for the dances, they were probably conceived for an aristocratic patronage connected with the Farnese, on the occasion of nuptial festivities celebrating marriages within this illustrious aristocratic family. With regard to the transcriptions, these too are by unknown hands, but it is possible to identify the original piece and trace the author of the latter. The composers identified for two works recorded here are Adrian Willaert, a Fleming active in northern Italy, and the Bolognese Domenico Maria Ferrabosco.

The ricercari, or ricercade. These are pieces whose formal structure is rather open, diverging from excessively strict vocal models in the direction of a writing already bound to the keyboard instrument. In these pages one finds numerous polyphonic sections, but also other elements such as diminutions, homophonic passages, melodic ideas, embellishments, chordal moments, echo dialogues. The stylistic diversity of the various authors, each in their specificity, highlights some characteristics over others from time to time.

The dances. There are two principal types of dance: the triptychs Pavana–Saltarello–Ripresa (or coda) and short dances each with a specific name. The triptychs have a more aristocratic character; the pavana in particular was the most dignified and poised dance, especially suited to noble dancing. The musical writing of the triptychs employs the right hand for the melody and diminutions, while the left hand presents for the most part parallel motion of chords in bare fifths, as harmonic and rhythmic support. A different case is that of the ‘Pavana de la bataglia – Il saltarello de la bataglia – La tedeschina’. This triptych, which recreates through music the character and certain onomatopoeic features of a battle, results from ideas, influences and adaptations derived from an illustrious model: the celebrated chanson ‘Escoutez tous gentilz’ by Janequin, inspired by the Battle of Marignano, which reached the Po Valley context close to Castell’Arquato through Francesco da Milano’s lute transcription.

The short dances have a more popular and lively character; they are arrangements of melodies, airs and dances then in circulation (some of which are also intabulated for lute in the same manuscripts). Certain titles, through the toponym indicated or the dialect employed, refer to the place of origin of the piece in northern Italy—mostly in Lombardy or the Veneto—or perhaps to the musician who performed them. In these pages the character of the musical writing is frequently chordal and percussive; the motion of the parts often presents parallelisms; the fundamental degrees of the chords in rapid succession sometimes create vivid colouristic effects, yielding particularly felicitous musical results despite the brevity of these pieces.

The transcriptions of vocal music. As examples there are presented a madrigal and a motet, both transcribed by an anonymous hand: Ferrabosco’s madrigal ‘Io mi son giovineta’, at the time extremely famous, and Willaert’s motet ‘O gloriosa domina’. The adaptation of the madrigal follows the design of the original piece faithfully, departing from it only in some diminutions and a few slight modifications. The rewriting of the motet (which is limited to the first part of Willaert’s polyphonic work), by contrast, is very free and little faithful to the original, from which it departs considerably—perhaps owing to particularly lacunose vocal parts available to the transcriber, perhaps also by virtue of a specific musical choice in arranging the work for keyboard instrument. In the case of Veggio’s canzona ‘La fugitiva’ as well, this is probably the version for keyboard instrument of a polyphonic piece, perhaps instrumental, which alternates mutually contrasting musical elements, managing to fuse them effectively in the bright and strongly profiled character proper to the canzona.

The musical section of the Archive of the Collegiate Church of Castell’Arquato places before us a panorama of forms and styles which, despite the rather small corpus that has come down to us, restores a cross-section of Renaissance musical life in Emilia in a small centre such as Castell’Arquato—perhaps peripheral in its location, yet up-to-date and inserted within the more illustrious musical context of its time.

![Bei Bei - Two Moons (2025) [Hi-Res] Bei Bei - Two Moons (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/19/j5lae93g4obtper3un20ilcnv.jpg)