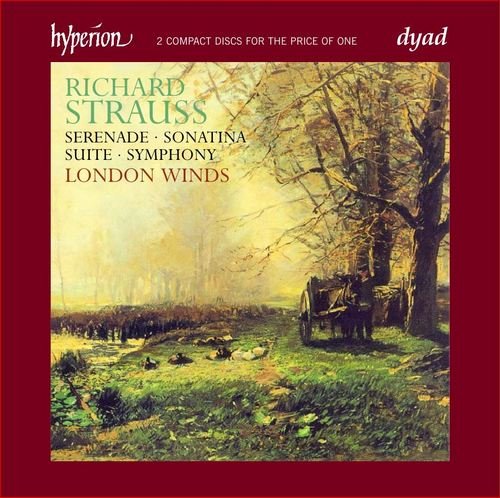

London Winds, Michael Collins - Richard Strauss: Sonatinen 1-2, Suite op. 4, Serenade op. 7 (1997)

Artist: London Winds, Michael Collins

Title: Richard Strauss: Sonatinen 1-2, Suite op. 4, Serenade op. 7

Year Of Release: 1997

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:45:19

Total Size: 421 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Richard Strauss: Sonatinen 1-2, Suite op. 4, Serenade op. 7

Year Of Release: 1997

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:45:19

Total Size: 421 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1:

[01]-[03] Sonatina No. 1 in F major "Aus des Werkstatt eines Invaliden"

[04]-[07] Suite in B flat major op. 4

CD 2:

[01] Serenade in E flat major op. 7

[02]-[05] Sonatina No. 2 in E flat major "Froehliche Werkstatt"

Performers:

London Winds

Michael Collins

The circumstances surrounding the composition and first performance of the Suite in B flat major, Op 4, were to prove enormously significant for Strauss’s career. Von Bülow decided to give the premiere of the new work in Munich in the winter of 1884 during an orchestral tour. Furthermore, since the players had already familiarized themselves with the music in Meiningen that autumn, he thought it would be appropriate if the composer himself conducted this performance according to his own interpretation. Never having directed an orchestra in public before, at short notice and with no rehearsal Strauss was thus launched headlong into his conducting career. Although marred somewhat by von Bülow’s legendary foul temper on the day of the concert (he seemed to be re-living bitter memories of his time in Munich and stamped around the warm-up room throughout the performance, unable to hear the music), Strauss’s unnerving directorial debut had been sufficiently successful to encourage von Bülow to offer him the post of assistant conductor at Meiningen six months later.

Similar in form and style to the Serenade, the opening Praeludium of the Suite has an even briefer ‘development’ section than that of the earlier work; it can only really be described as an intervening episode. Nevertheless, as in the Serenade, references are made here to rhythms and fragments of themes which have played an important role during the opening of the movement. The material of this episode also appears later as part of the coda, a feature which, together with evidence of Strauss’s increasing maturity in idiomatic writing for individual instruments and awareness of texture, mitigates any sense of formal weakness.

The Romanze is a gentle Andante in which a typically terse principal theme is contrasted with a distinctive transitional fanfare idea for horn and lyrical solos for clarinet and oboe forming the second subject. Much of this material was clearly inspired by the distinguished personnel of the Meiningen orchestra. The Gavotte which follows is a lively and appealing rhythmic tour de force, full of colour and the most beguiling and adroit attention to textural detail.

The lyrical second theme from the Romanze appears again in the Introduction of the final movement, after which comes the complex and carefully constructed Fugue. Opinion is divided as to whether or not this Fugue is too contrived. Whatever one’s ultimate view, there can be no doubting the expertise of the youthful composer who employs inversions, augmentations, diminutions, and stretti, and who combines the Fugue subject with episodic themes so successfully in such an audacious display of compositional technique. It is perhaps no wonder that Strauss later commented in connection with this work, ‘Happy days of my youth, when I could still work to order’.

In a letter of 1943 to Willi Schuh, Strauss wrote that he considered his life’s work to have ended with the opera Capriccio (1940/1). However, far from signalling a period of compositional retirement, the 1940s in fact heralded the start of an important final phase of Strauss’s creativity in which works such as the two Sonatinas for wind, the second horn concerto and Metamorphosen for strings figure prominently. Strauss’s somewhat dismissive and certainly over-modest reference to these and other works as ‘exercises for my wrist’ is clearly not applicable.

Similar in form and style to the Serenade, the opening Praeludium of the Suite has an even briefer ‘development’ section than that of the earlier work; it can only really be described as an intervening episode. Nevertheless, as in the Serenade, references are made here to rhythms and fragments of themes which have played an important role during the opening of the movement. The material of this episode also appears later as part of the coda, a feature which, together with evidence of Strauss’s increasing maturity in idiomatic writing for individual instruments and awareness of texture, mitigates any sense of formal weakness.

The Romanze is a gentle Andante in which a typically terse principal theme is contrasted with a distinctive transitional fanfare idea for horn and lyrical solos for clarinet and oboe forming the second subject. Much of this material was clearly inspired by the distinguished personnel of the Meiningen orchestra. The Gavotte which follows is a lively and appealing rhythmic tour de force, full of colour and the most beguiling and adroit attention to textural detail.

The lyrical second theme from the Romanze appears again in the Introduction of the final movement, after which comes the complex and carefully constructed Fugue. Opinion is divided as to whether or not this Fugue is too contrived. Whatever one’s ultimate view, there can be no doubting the expertise of the youthful composer who employs inversions, augmentations, diminutions, and stretti, and who combines the Fugue subject with episodic themes so successfully in such an audacious display of compositional technique. It is perhaps no wonder that Strauss later commented in connection with this work, ‘Happy days of my youth, when I could still work to order’.

In a letter of 1943 to Willi Schuh, Strauss wrote that he considered his life’s work to have ended with the opera Capriccio (1940/1). However, far from signalling a period of compositional retirement, the 1940s in fact heralded the start of an important final phase of Strauss’s creativity in which works such as the two Sonatinas for wind, the second horn concerto and Metamorphosen for strings figure prominently. Strauss’s somewhat dismissive and certainly over-modest reference to these and other works as ‘exercises for my wrist’ is clearly not applicable.

DOWNLOAD LINKS

![Tomasz Stańko - Piece for Diana and Other Ballads (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 1/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stańko - Piece for Diana and Other Ballads (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 1/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765788761_cover.jpg)