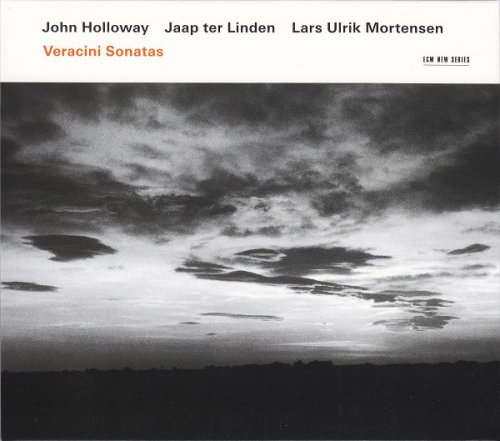

John Holloway, Jaap ter Linden, Lars Ulrik Mortensen - Francesco Maria Veracini: Sonatas (2005)

Artist: John Holloway, Jaap ter Linden, Lars Ulrik Mortensen

Title: Francesco Maria Veracini: Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 60:01

Total Size: 385 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Francesco Maria Veracini: Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 60:01

Total Size: 385 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Sonata No.1 from Sonate a violino solo e basso op.1

01. I. Overtura. Largo - Allegro 05:40

02. II. Aria. Affetuoso 04:41

03. III. Paesana. Allegro 01:52

04. IV. Minuet. Allegro 01:20

05. V. Giga "Postiglione". Allegro 04:35

Sonata No.5 from Sonate a violino, o flauto solo, e basso

06. I. Largo 02:18

07. II. Allegro 02:17

08. III. Largo 02:53

09. IV. Allegro 03:23

Sonata No.1 from Dissertazioni...sopra I'opera guinta del Corelli

10. I. Preludio 03:12

11. II. Allegro 02:42

12. III. Allegro 01:02

13. IV. Adagio 02:52

14. V. Allegro 02:12

Sonata No.6 from Sonate accademiche op.2

15. I. Siciliana. Larghetto 03:07

16. II. Capriccio. Allegro, e con affetto 05:02

17. III. Andante moderato 03:28

18. IV. Largo 05:38

19. V. Allegro assai 03:30

Performers:

John Holloway (violin)

Jaap ter Linden (violoncello)

Lars Ulrik Mortensen (harpsichord)

Vain, arrogant, and eccentric, yet at the same time one of the most dazzling violinists of the age, the Florentine Francesco Maria Veracini (1690–1768) certainly cuts a colorful figure on the stage of 18th-century music. “There is but one God, and one Veracini,” he is said by Charles Burney to have proclaimed. The English music historian also noted the dramatic difference in character between Veracini and his rival Tartini, recording that while Tartini was “humble and timid,” the former was “foolishly vain-glorious.” During the course of an itinerant career stretching over more than 50 years, numerous anecdotes relating to Veracini’s eccentric and ill-mannered behavior circulated throughout Europe, some doubtless apocryphal. Veracini’s playing must have been exceptional, although characterized more by extroversion than finesse, if contemporary accounts are anything to go by. The French traveler Charles de Brosses heard him in Florence in 1739, commenting on playing that was “noble, knowledgeable, and precise, but a little lacking in grace,” while Burney noted that Veracini’s tone was “so loud and clear” that it easily dominated even a large theater band.

There are five sets of violin sonatas by Veracini, from four of which John Holloway has selected representative examples. The earliest, in C Major, is from an unpublished group dating from the composer’s second visit to Venice (1716). Described as appropriate for violin or recorder, they were dedicated to Crown Prince Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who was shortly to persuade his father to engage Veracini in Dresden. In two respects they are unique among Veracini’s sonatas: the optional scoring means they are largely devoid of the technical difficulties found in the other violin sonatas, and they are the only sonatas to adopt the four-movement Vivaldian format, if not style. The C-Major Sonata is an appealing work, particularly in its two largos, the first a gracious, dotted-rhythm movement, elegantly played by Holloway, the second an expressive, elaborately ornamented cantabile over a walking bass.

The remaining sonatas all conform to the Corellian five-movement pattern, both op. 1 of 1721 and op. 2, the Sonate accademiche (1744), which are also dedicated to Frederick Augustus (by this time Elector), paying homage to their model by dividing the publications into groups of six each of sonate da chiesa and sonate da camera. In his final set, composed around 1760, Veracini takes the Corellian link a step further by directly basing his sonatas on Dissertazione, as he called them, on Corelli’s seminal op. 5 violin sonatas. As John Holloway points out in his notes, Veracini’s gloss on Corelli does not consist of ornamental elaboration, but rather on extending the contrapuntal possibilities already inherent in Corelli’s writing, in the case of the D-Major Sonata primarily in the opening and closing movements.

If less in evidence than in the op. 2 Sonatas, those of op. 1 already include some of the bizarre elements for which Veracini was noted. As befits the first work of a published set, it opens with an ambitious French overture succeeded by a moderately paced triple-time dance movement whose natural galant mannerisms are disrupted in its first strain by chromatic slitherings, here most tellingly played. The final Gigue makes colorful use of posthorn calls. The Sonate accademiche remain Veracini’s most enduring publication, noted particularly for their capriccios, movements in which their composer cleverly juxtaposed elements of the bizzarie for which he was famed with his love of counterpoint. They have attracted a number of violinists, most notably the Locatelli Trio’s Elizabeth Wallfisch, whose superb complete set on Hyperion I reviewed in Fanfare 19:2. Comparing the two versions of No. 6, I in fact came away with a distinct preference for Wallfisch, not only because her quicker tempos in the two slower movements seem to me to work better than Holloway’s (his opening Siciliana in particular sounds uncharacteristically labored), but because of her more refined tone and greater sense of nuance.

Notwithstanding this caveat, there is here as much to enjoy, even relish, as one would expect from a player of Holloway’s caliber. Particularly in more virtuosic music, his playing is superbly assured, with chords and double stopping projected with a full, rich tone that one imagines must have been the hallmark of Veracini’s own playing. ECM has matched this with sound of brightly-lit immediacy, although there are times when I wonder if Mortensen’s harpsichord might have been more in the picture. If perhaps not as remarkable as Holloway’s Biber, this still warrants a strong recommendation. -- Brian Robins

There are five sets of violin sonatas by Veracini, from four of which John Holloway has selected representative examples. The earliest, in C Major, is from an unpublished group dating from the composer’s second visit to Venice (1716). Described as appropriate for violin or recorder, they were dedicated to Crown Prince Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who was shortly to persuade his father to engage Veracini in Dresden. In two respects they are unique among Veracini’s sonatas: the optional scoring means they are largely devoid of the technical difficulties found in the other violin sonatas, and they are the only sonatas to adopt the four-movement Vivaldian format, if not style. The C-Major Sonata is an appealing work, particularly in its two largos, the first a gracious, dotted-rhythm movement, elegantly played by Holloway, the second an expressive, elaborately ornamented cantabile over a walking bass.

The remaining sonatas all conform to the Corellian five-movement pattern, both op. 1 of 1721 and op. 2, the Sonate accademiche (1744), which are also dedicated to Frederick Augustus (by this time Elector), paying homage to their model by dividing the publications into groups of six each of sonate da chiesa and sonate da camera. In his final set, composed around 1760, Veracini takes the Corellian link a step further by directly basing his sonatas on Dissertazione, as he called them, on Corelli’s seminal op. 5 violin sonatas. As John Holloway points out in his notes, Veracini’s gloss on Corelli does not consist of ornamental elaboration, but rather on extending the contrapuntal possibilities already inherent in Corelli’s writing, in the case of the D-Major Sonata primarily in the opening and closing movements.

If less in evidence than in the op. 2 Sonatas, those of op. 1 already include some of the bizarre elements for which Veracini was noted. As befits the first work of a published set, it opens with an ambitious French overture succeeded by a moderately paced triple-time dance movement whose natural galant mannerisms are disrupted in its first strain by chromatic slitherings, here most tellingly played. The final Gigue makes colorful use of posthorn calls. The Sonate accademiche remain Veracini’s most enduring publication, noted particularly for their capriccios, movements in which their composer cleverly juxtaposed elements of the bizzarie for which he was famed with his love of counterpoint. They have attracted a number of violinists, most notably the Locatelli Trio’s Elizabeth Wallfisch, whose superb complete set on Hyperion I reviewed in Fanfare 19:2. Comparing the two versions of No. 6, I in fact came away with a distinct preference for Wallfisch, not only because her quicker tempos in the two slower movements seem to me to work better than Holloway’s (his opening Siciliana in particular sounds uncharacteristically labored), but because of her more refined tone and greater sense of nuance.

Notwithstanding this caveat, there is here as much to enjoy, even relish, as one would expect from a player of Holloway’s caliber. Particularly in more virtuosic music, his playing is superbly assured, with chords and double stopping projected with a full, rich tone that one imagines must have been the hallmark of Veracini’s own playing. ECM has matched this with sound of brightly-lit immediacy, although there are times when I wonder if Mortensen’s harpsichord might have been more in the picture. If perhaps not as remarkable as Holloway’s Biber, this still warrants a strong recommendation. -- Brian Robins

DOWNLOAD LINKS

![Bianca Stücker, Mark Benecke - Abysmal Affairs (2026) [Hi-Res] Bianca Stücker, Mark Benecke - Abysmal Affairs (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/09/2typt3jts14d31ka1yq47fdjt.jpg)