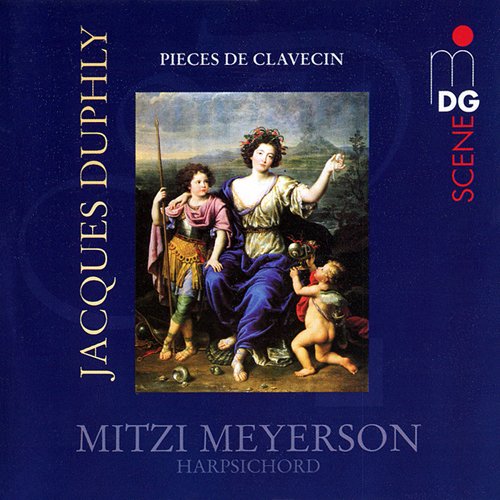

Mitzi Meyerson - Duphly, Jacques: Pieces de Clavecin (2001)

Artist: Mitzi Meyerson

Title: Duphly, Jacques: Pieces de Clavecin

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: MDG

Genre: baroque / harpsichord

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 62:27

Total Size: 514 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Duphly, Jacques: Pieces de Clavecin

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: MDG

Genre: baroque / harpsichord

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 62:27

Total Size: 514 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Chaconne (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

2. La Pothouin, Rondeau, moderement (Quatrieme Livre, 1768)

3. La de la Tour, vivement (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

4. Menuets (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

5. La De Belombre, vivement (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

6. La du Buq (Quatrieme Livre, 1768)

7. La Millettina (Premier Livre, 1744)

8. Allemande en do (Premier Livre, 1744)

9. Medee, vivement et fort (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

10. La Forqueray, Rondeau (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

11. La de Vaucanson (Quatrieme Livre, 1768)

12. La Tribolet, vivement (Premier Livre, 1744)

13. Cazamajor (Premier Livre, 1744)

14. La de Villeneuve, Gavotte, tendrement (Troisieme Livre, 1756)

15. La Lanza, noblement et vif (Deuxieme Livre, 1748)

Jacques Duphly is best known to harpsichordists for the four collections of harpsichord pieces he published in Paris between 1744 and 1768. These are spirited and pungent works, finely crafted in the tradition of Francois Couperin (in the Rondeau in D minor Duphly pays homage to Les Barricades mysterieuses) and emboldened by the manner of the Forquerays (in La Felix as well as La Forqueray). Mitzi Meyerson understands and relishes this music, with its beguiling sequences: her performances are arresting and delightfully unpredictable.

Rather than playing a series of movements from single suites, she has mixed them up, alternating character pieces and dance movements; Italianate and more traditional French-styled movements, in different keys and from different books. On the one hand, she maximizes contrasts of style, tessitura (the pieces exploit different registers of the harpsichord: Les Graces is set in the treble, the Courante in D minor in the middle and La Forqueray in the bass) and mood not otherwise possible; on the other, she builds on the tension between them. Nicholas Anderson's note explores the inscriptions, many of which refer to members of the circle of musicians and artists who congregated around the wealthy, music-loving Alexandre-Jean-Joseph Le Riche de La Poupliniere; Anne-Jeanne Boucon, a pupil of his music master Rameau, was in fact the wife of Mondonville, not Forqueray.

Meyerson is a decisive player, sensitive to the rhetoric of the French classical style. Her command of the dramatic power of silence— from the hairbreadth created by subtle articulation (as in La Boucon and Les Graces) to the grand pause (the opening Legerement and La Vanlo)—is a particular delight. In the menuets she is witty; elsewhere she is flamboyant, never more so than in La Victoire. She indulges in rubato and rits, but does so convincingly. Nicholas Parker's recording is delightfully resonant, as befits the rich harmonic language of the music (enhanced by the variation in temperaments used) and the vitality of Meyerson's performances.'

Rather than playing a series of movements from single suites, she has mixed them up, alternating character pieces and dance movements; Italianate and more traditional French-styled movements, in different keys and from different books. On the one hand, she maximizes contrasts of style, tessitura (the pieces exploit different registers of the harpsichord: Les Graces is set in the treble, the Courante in D minor in the middle and La Forqueray in the bass) and mood not otherwise possible; on the other, she builds on the tension between them. Nicholas Anderson's note explores the inscriptions, many of which refer to members of the circle of musicians and artists who congregated around the wealthy, music-loving Alexandre-Jean-Joseph Le Riche de La Poupliniere; Anne-Jeanne Boucon, a pupil of his music master Rameau, was in fact the wife of Mondonville, not Forqueray.

Meyerson is a decisive player, sensitive to the rhetoric of the French classical style. Her command of the dramatic power of silence— from the hairbreadth created by subtle articulation (as in La Boucon and Les Graces) to the grand pause (the opening Legerement and La Vanlo)—is a particular delight. In the menuets she is witty; elsewhere she is flamboyant, never more so than in La Victoire. She indulges in rubato and rits, but does so convincingly. Nicholas Parker's recording is delightfully resonant, as befits the rich harmonic language of the music (enhanced by the variation in temperaments used) and the vitality of Meyerson's performances.'