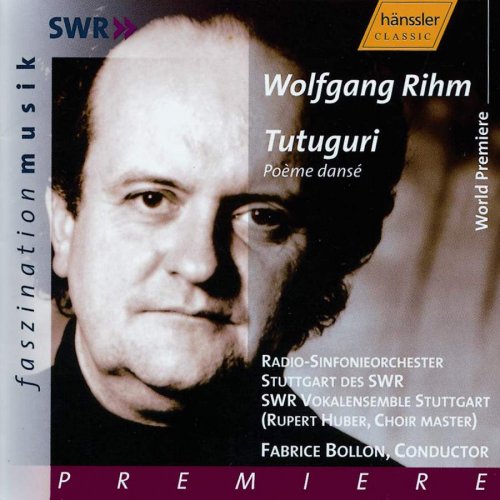

Fabrice Bollon - Rihm: Tutuguri (2002)

Artist: SWR Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Fabrice Bollon

Title: Rihm: Tutuguri

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Hänssler Classic

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

Total Time: 1:56:50

Total Size: 476 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Rihm: Tutuguri

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Hänssler Classic

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

Total Time: 1:56:50

Total Size: 476 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1

Erster Teil

[1]-[2] I. Bild

[3] II. Bild

[4] III. Bild

CD 2

Zweiter Teil

[1] IV. Bild

Performers:

Rupert Huber

David Haller

SWR Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra

Fabrice Bollon

Tutuguri: Poème dansé, after Artaud, is obliquely inspired by Artaud’s poem Tutuguri – Le rite du soleil noir in his radiophonic "play" Pour en finir avec le jugement de Dieu of 1948 as well as by Artaud’s life and work in general. Antonin Artaud (1896 – 1948), actor, playwright and stage director, was once a member of the French surrealist circle which he left when he realised the Surrealists’ Communist leanings. From early on, he suffered from nervous and mental disorders, often cured by various drugs to which he remained addicted throughout his life. In the late 1930s he undertook a trip to Mexico in an attempt to get rid of his drug addiction - an effort only partly successful. All his life he was an independent mind often in conflict with his environment. He wrote fiery, vengeful and sometimes frankly aggressive letters to personalities as Paul Claudel. His writings on the theatre had a lasting influence on many generations of actors and stage directors such as Jean-Louis Barrault. However, his often eccentric behaviour caused by his physical and mental ill-health was such that he spent many years in lunatic asylums. He died of cancer in 1948.

The poem Tutuguri – Le rite du soleil noir is an apocalyptic, if rather enigmatic vision of death and destruction, ending with the blasphemous image of the Cross replaced by a huge horseshoe dipped in the rider’s blood. It calls forth some strong verbal imagery which undoubtedly impressed Rihm and had him thinking about a large-scale piece based on the poem as well as on Artaud’s life and work. (The third tableau alludes to the Peyotl dance, i.e. an episode of Artaud’s Mexican trip.) Rihm describes the poem as the "presentation of a dark, fierce cult". In Artaud’s words: "Now, the key of the Rite is precisely/THE ABOLITION OF THE CROSS". Tutuguri for speaker, chorus and large orchestra with a huge percussion section consists of four sizeable tableaux. The first, bipartite tableau opens with a long introduction. The music arises, as it were, out of the void with a lonely flute soon engulfed in some frantic percussive music. The second part is mostly for orchestra, still with much percussion, alternating almost static episodes and wildly energetic, heavily pounding passages sometimes reminiscent of Varèse or of Xenakis. About halfway into the movement, the chorus has its first entry with rhythmic delivery of vowels and syllables accompanied by hand clapping. (Neither the chorus nor the speaker ever use words or parts of the poem.) Roughly speaking, the second tableau might be seen as the slow movement, though it is full of dynamic extremes (a Rihm characteristic, if ever there was one). Rattling percussion opens the third tableau (The Peyotl dance) in a mysterious, menacing mood leading into an insistent, obstinate dance, again with percussion much to the fore. Halfway through the movement, the chorus has its second brief entry. A slower section slowly leads into the violent coda (again shouts from the chorus with much percussion accompaniment). The fourth tableau, the longest (and, to my mind, the weakest) is a long movement entirely scored for percussion including some shouting (from the chorus? From the players? Or both?).

Rihm’s expressionistic music often makes its point by its sheer volume and its almost visceral energy, and often relies on contrasting dynamic extremes. As such, it is well suited to Artaud’s catastrophic, nihilistic vision. There is no denying the sincerity of Rihm’s response to Artaud’s text. However, the piece is, I think, far too long and even rambling at times. In short, it may be too much of a good thing; and its global impact might have been still greater had the piece been more concise … more incisive. All in all, however, it is a considerable achievement in its own right. A very demanding piece, taxing the players’ and the listeners’ endurance. The percussion players deserve wholehearted praise for their tireless energy, and so does Fabrice Bollon for leading his huge forces with a sure hand throughout this long, cataclysmic work. Quite an experience, I must say, but not one I would want every day. ~ Hubert Culot

The poem Tutuguri – Le rite du soleil noir is an apocalyptic, if rather enigmatic vision of death and destruction, ending with the blasphemous image of the Cross replaced by a huge horseshoe dipped in the rider’s blood. It calls forth some strong verbal imagery which undoubtedly impressed Rihm and had him thinking about a large-scale piece based on the poem as well as on Artaud’s life and work. (The third tableau alludes to the Peyotl dance, i.e. an episode of Artaud’s Mexican trip.) Rihm describes the poem as the "presentation of a dark, fierce cult". In Artaud’s words: "Now, the key of the Rite is precisely/THE ABOLITION OF THE CROSS". Tutuguri for speaker, chorus and large orchestra with a huge percussion section consists of four sizeable tableaux. The first, bipartite tableau opens with a long introduction. The music arises, as it were, out of the void with a lonely flute soon engulfed in some frantic percussive music. The second part is mostly for orchestra, still with much percussion, alternating almost static episodes and wildly energetic, heavily pounding passages sometimes reminiscent of Varèse or of Xenakis. About halfway into the movement, the chorus has its first entry with rhythmic delivery of vowels and syllables accompanied by hand clapping. (Neither the chorus nor the speaker ever use words or parts of the poem.) Roughly speaking, the second tableau might be seen as the slow movement, though it is full of dynamic extremes (a Rihm characteristic, if ever there was one). Rattling percussion opens the third tableau (The Peyotl dance) in a mysterious, menacing mood leading into an insistent, obstinate dance, again with percussion much to the fore. Halfway through the movement, the chorus has its second brief entry. A slower section slowly leads into the violent coda (again shouts from the chorus with much percussion accompaniment). The fourth tableau, the longest (and, to my mind, the weakest) is a long movement entirely scored for percussion including some shouting (from the chorus? From the players? Or both?).

Rihm’s expressionistic music often makes its point by its sheer volume and its almost visceral energy, and often relies on contrasting dynamic extremes. As such, it is well suited to Artaud’s catastrophic, nihilistic vision. There is no denying the sincerity of Rihm’s response to Artaud’s text. However, the piece is, I think, far too long and even rambling at times. In short, it may be too much of a good thing; and its global impact might have been still greater had the piece been more concise … more incisive. All in all, however, it is a considerable achievement in its own right. A very demanding piece, taxing the players’ and the listeners’ endurance. The percussion players deserve wholehearted praise for their tireless energy, and so does Fabrice Bollon for leading his huge forces with a sure hand throughout this long, cataclysmic work. Quite an experience, I must say, but not one I would want every day. ~ Hubert Culot

![Black Flower - Motions EP (2026) [Hi-Res] Black Flower - Motions EP (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772813045_cover.jpg)

![Shabaka - Of The Earth (2026) [Hi-Res] Shabaka - Of The Earth (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772619684_m8nqadiywwn9z_600.jpg)

![Marcelo Callado - Brado (2026) [Hi-Res] Marcelo Callado - Brado (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/05/adfw4sptct8h9asxk5azgqtx0.jpg)

![Aaron Irwin Trio - Spark (2026) [Hi-Res] Aaron Irwin Trio - Spark (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772720004_g7cowfu3nhxss_600.jpg)

![Blue Mitchell - Funktion Junction (2026) [Hi-Res] Blue Mitchell - Funktion Junction (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772758546_waiec07ivtzgr_600.jpg)