Miles Okazaki - Trickster (2017)

Artist: Miles Okazaki

Title: Trickster

Year Of Release: 2017

Label: Pi

Genre: Modern Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 44:41

Total Size: 269.1 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Trickster

Year Of Release: 2017

Label: Pi

Genre: Modern Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 44:41

Total Size: 269.1 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Kudzu

2. Mischief

3. Box in a Box

4. Eating Earth

5. Black Bolt

6. The West

7. The Calendar

8. Caduceus

9. Borderland

Trickster is guitarist Miles Okazaki’s first album in five years and his much anticipated debut on Pi Recordings, having been featured on six other releases in the label’s catalog in groups led by Steve Coleman, Jonathan Finlayson, and Dan Weiss, along with associations with other Pi artists such as Matt Mitchell, Jen Shyu, and Amir ElSaffar. Perhaps best-known as a member of Steve Coleman and Five Elements, with whom he has played for the last eight years, Okazaki has also built a solid reputation for himself as one of the most adventurous composers and guitarists on the current scene. The New York Times says of Okazaki, “Even by the standard of his hyper-literate post-bop peer group, Mr. Okazaki is an unusually calculating musical thinker,” and as a guitarist, “exceedingly skilled with a head for rhythmic convolution.”

Originally from Port Townsend, Washington, Okazaki began playing classical guitar at age six, and was playing regular gigs on electric guitar by age fourteen. He moved to New York after graduating from Harvard University (he also holds degrees from Manhattan School of Music and The Juilliard School) to pursue a career in music. His teacher on guitar at the time was Rodney Jones, who got Okazaki’s career in motion by recommending him for early gigs with Stanley Turrentine, Lenny Pickett, Regina Carter, and studio session work. He has received many awards as a guitarist including placing second in the 2005 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition. Okazaki spent four years on the road with vocalist Jane Monheit and became known as an expert vocal accompanist, but he also started to develop an experimental streak in his own music. His first album as a leader, Mirror (2006), received a “Critics Pick” in the New York Times, who called it “a work of sustained collectivity as well as deep intricacy.” His second album, Generations (2009), was described by pianist Vijay Iyer in Artforum as “the sonic equivalent of Escher or Borges, but with real emotional heft.” His next album, Figurations, was selected as one of the New York Times top ten albums of 2012, described by Ben Ratliff as “slowly evolving puzzles of brilliant jazz logic.”

Okazaki subsequently entered a period of focused guitar study, which resulted in the book Fundamentals of Guitar, published by Mel Bay in 2015. When he began to compose again, he went at it from a fresh perspective, placing greater emphasis on guitar playing and improvisation. Steve Coleman describes Okazaki’s development during this period: Miles has always been a very intense cat. Ive always been impressed with his perseverance and how deep he gets into his research. When he first came to me years ago, all he wanted to talk about was conceptual stuff, but now that hes internalized it, it just comes out organically. You can really hear that in his playing now. For his new music, Okazaki decided to use Anthony Tidd on bass and Sean Rickman on drums, the long-running rhythmic engine and his bandmates in Steve Coleman and Five Elements, with whom he has performed with hundreds of times. Its a fascinating opportunity to hear their unique chemistry — the quicksilver ability to process and internalize complex information, transform musical material

Through improvisation, and do it all while staying “in the pocket” — in a wholly different context. Both Tidd and Rickman have deep roots in funk, R&B, and hip hop, and it is fascinating to hear Okazaki’s music through the filter of these musical sensibilities. Okazaki’s next call went to pianist Craig Taborn, perhaps the most widely-admired pianist on the cutting-edge of jazz, who brings a supremely inventive musical sense to everything he plays. Together they have created a breakthrough statement by Okazaki, a unified book of compositions that grooves from beginning to end.

Trickster was originally inspired by Lewis Hyde’s book Trickster Makes This World. As Okazaki describes it, “The trickster figure is an ancient archetype in human folklore. They are creative in nature, using mischief and magic to disrupt the state of things, breaking taboos and conventions, opening doorways. They exist outside of the mainstream, working from the margins, creating movement across the borders. They cause damage and they heal. They are storytellers and improvisers.” He specifically chose the stories of Eshu, Raven, Krishna, Heyoka, Thoth, and Hermes, with their themes of mischief, disguise, paradox, chaos, illusion, and balance as the basis of musical structures and improvisations. One can get a sense of the trickster narratives by following the rhythms, which have many twists and turns and are not always what they seem to be. For example, “Box in a Box,” which tell a story of Raven, a trickster from the native peoples of the Salish Sea in the Pacific Northwest, in which he disguises himself as a child to steal the light of the world that is hidden in the center of an infinite number of nested boxes. The composition works at this feeling of continual unboxing through a number of musical devices: rotating all-interval tetrachords, their intersection with symmetrical melodies, a perpetually shape-shifting bassline, an illusory drum figure. This machinery all fits into a conventional, square-shaped musical form. In “Eating Earth,” which comes from the Indian tale of Krishna, whose mother asked to look in his mouth when he was accused of eating dirt, only to see the entire universe inside. She even sees herself looking into her son’s mouth — the whole contained within the part. In this composition, each instrument floats through time at different speeds, colliding and combining into sonic constellations, never forming the same shape twice. This method of disguising intricate compositional machinery in a relaxed, earthy rhythmic flow has become Okazaki’s newfound style.

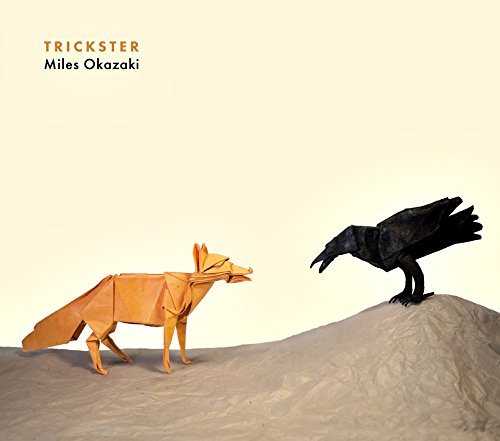

Another inspiration for the music comes from the Japanese art of origami, in which all models are made by folding a single uncut square of paper. According to Okazaki, “I’ve always believed in the idea that working within constraints focuses creativity, sharpens technique, and ultimately leads to greater freedom than having no boundaries at all. The central challenge of origami is to create new forms from one basic shape. All of the compositions on this album are contained within simple shapes - 12 or 16 bars of 4/4 or 3/4. But this fact is largely disguised by various rhythmic illusions and internal ‘folds’ within the form.” His folded models of fox and raven, two trickster animals, appear on the album cover. The back cover shows the papers after the models are unfolded, revealing their internal geometry in a pattern of creases that has a beauty of their own.

The music on Trickster is designed to encourage risk-taking. There are many traps and deceptions, but navigating through these spaces open possibility of discovering new territory. Craig Taborn addresses this idea: “You have to give it up to a trickster. You have to engage with this chaotic element where you really don’t know how it may go. And not only that, trickster deities are very neutral, they don’t really care. That energy doesn’t want you to win or not win. It can go either way, but you have to propitiate it and engage with it, hoping for some kind of beneficial or positive outcome. But you have to be willing to flow with the other thing too, and that’s what it takes to really improvise.”

Originally from Port Townsend, Washington, Okazaki began playing classical guitar at age six, and was playing regular gigs on electric guitar by age fourteen. He moved to New York after graduating from Harvard University (he also holds degrees from Manhattan School of Music and The Juilliard School) to pursue a career in music. His teacher on guitar at the time was Rodney Jones, who got Okazaki’s career in motion by recommending him for early gigs with Stanley Turrentine, Lenny Pickett, Regina Carter, and studio session work. He has received many awards as a guitarist including placing second in the 2005 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition. Okazaki spent four years on the road with vocalist Jane Monheit and became known as an expert vocal accompanist, but he also started to develop an experimental streak in his own music. His first album as a leader, Mirror (2006), received a “Critics Pick” in the New York Times, who called it “a work of sustained collectivity as well as deep intricacy.” His second album, Generations (2009), was described by pianist Vijay Iyer in Artforum as “the sonic equivalent of Escher or Borges, but with real emotional heft.” His next album, Figurations, was selected as one of the New York Times top ten albums of 2012, described by Ben Ratliff as “slowly evolving puzzles of brilliant jazz logic.”

Okazaki subsequently entered a period of focused guitar study, which resulted in the book Fundamentals of Guitar, published by Mel Bay in 2015. When he began to compose again, he went at it from a fresh perspective, placing greater emphasis on guitar playing and improvisation. Steve Coleman describes Okazaki’s development during this period: Miles has always been a very intense cat. Ive always been impressed with his perseverance and how deep he gets into his research. When he first came to me years ago, all he wanted to talk about was conceptual stuff, but now that hes internalized it, it just comes out organically. You can really hear that in his playing now. For his new music, Okazaki decided to use Anthony Tidd on bass and Sean Rickman on drums, the long-running rhythmic engine and his bandmates in Steve Coleman and Five Elements, with whom he has performed with hundreds of times. Its a fascinating opportunity to hear their unique chemistry — the quicksilver ability to process and internalize complex information, transform musical material

Through improvisation, and do it all while staying “in the pocket” — in a wholly different context. Both Tidd and Rickman have deep roots in funk, R&B, and hip hop, and it is fascinating to hear Okazaki’s music through the filter of these musical sensibilities. Okazaki’s next call went to pianist Craig Taborn, perhaps the most widely-admired pianist on the cutting-edge of jazz, who brings a supremely inventive musical sense to everything he plays. Together they have created a breakthrough statement by Okazaki, a unified book of compositions that grooves from beginning to end.

Trickster was originally inspired by Lewis Hyde’s book Trickster Makes This World. As Okazaki describes it, “The trickster figure is an ancient archetype in human folklore. They are creative in nature, using mischief and magic to disrupt the state of things, breaking taboos and conventions, opening doorways. They exist outside of the mainstream, working from the margins, creating movement across the borders. They cause damage and they heal. They are storytellers and improvisers.” He specifically chose the stories of Eshu, Raven, Krishna, Heyoka, Thoth, and Hermes, with their themes of mischief, disguise, paradox, chaos, illusion, and balance as the basis of musical structures and improvisations. One can get a sense of the trickster narratives by following the rhythms, which have many twists and turns and are not always what they seem to be. For example, “Box in a Box,” which tell a story of Raven, a trickster from the native peoples of the Salish Sea in the Pacific Northwest, in which he disguises himself as a child to steal the light of the world that is hidden in the center of an infinite number of nested boxes. The composition works at this feeling of continual unboxing through a number of musical devices: rotating all-interval tetrachords, their intersection with symmetrical melodies, a perpetually shape-shifting bassline, an illusory drum figure. This machinery all fits into a conventional, square-shaped musical form. In “Eating Earth,” which comes from the Indian tale of Krishna, whose mother asked to look in his mouth when he was accused of eating dirt, only to see the entire universe inside. She even sees herself looking into her son’s mouth — the whole contained within the part. In this composition, each instrument floats through time at different speeds, colliding and combining into sonic constellations, never forming the same shape twice. This method of disguising intricate compositional machinery in a relaxed, earthy rhythmic flow has become Okazaki’s newfound style.

Another inspiration for the music comes from the Japanese art of origami, in which all models are made by folding a single uncut square of paper. According to Okazaki, “I’ve always believed in the idea that working within constraints focuses creativity, sharpens technique, and ultimately leads to greater freedom than having no boundaries at all. The central challenge of origami is to create new forms from one basic shape. All of the compositions on this album are contained within simple shapes - 12 or 16 bars of 4/4 or 3/4. But this fact is largely disguised by various rhythmic illusions and internal ‘folds’ within the form.” His folded models of fox and raven, two trickster animals, appear on the album cover. The back cover shows the papers after the models are unfolded, revealing their internal geometry in a pattern of creases that has a beauty of their own.

The music on Trickster is designed to encourage risk-taking. There are many traps and deceptions, but navigating through these spaces open possibility of discovering new territory. Craig Taborn addresses this idea: “You have to give it up to a trickster. You have to engage with this chaotic element where you really don’t know how it may go. And not only that, trickster deities are very neutral, they don’t really care. That energy doesn’t want you to win or not win. It can go either way, but you have to propitiate it and engage with it, hoping for some kind of beneficial or positive outcome. But you have to be willing to flow with the other thing too, and that’s what it takes to really improvise.”

![Eero Koivistoinen - For Children (1970) [2006] Eero Koivistoinen - For Children (1970) [2006]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771615516_ff.jpg)

![Moonchild - Waves (2026) [Hi-Res] Moonchild - Waves (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771498123_a3922124048_10.jpg)