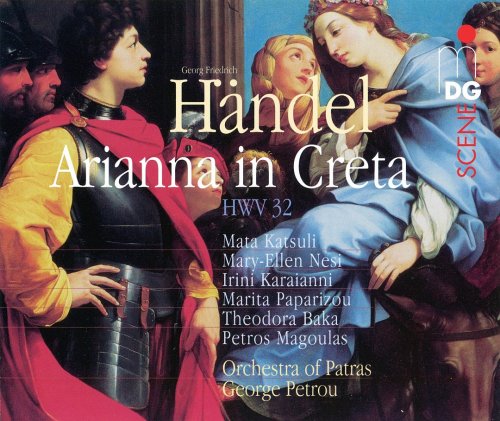

George Petrou - Handel: Arianna in Creta (2005)

Artist: George Petrou

Title: Händel: Arianna in Creta, HWV 32

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Md&G Records

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

Total Time: 2:43:47

Total Size: 777 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: Händel: Arianna in Creta, HWV 32

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Md&G Records

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

Total Time: 2:43:47

Total Size: 777 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

This is the first commercial recording of Arianna in Creta but, just as importantly, it is also the last of Handel’s surviving operas to be issued on CD (now can we please record at least a third of them again in performances they deserve?). Handel, according to his usual practice for the London stage, chose to set an old Italian libretto: Arianna e Teseo set by Leonardo Leo for Rome in 1729, although a few of Handel’s aria texts were instead taken from a pasticcio that his new London rival Porpora had organised at Naples in 1721.

Handel’s opera portrays Theseus’ love affair with the Cretan King Minos’ daughter Ariadne, the hero’s victory over the Minotaur, and his escape from the labyrinth. It ends happily, with the sentiment that love overcomes cruelty. None of the later dejection when Ariadne is forsaken on Naxos is portrayed.

Curiously, Porpora and the ‘Opera of the Nobility’ organised Arianna in Nasso at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on December 29, 1733, just under a month before Handel’s treatment of the Theseus and Ariadne story could make it to the King’s Theatre stage. However, Handel’s opera was a much greater success, notching up 16 performances and earning a prompt revival at the beginning of the following season. Produced between Orlando and Ariodante, Arianna in Creta does not quite match the pinnacles that surround it in the chronology of Handel’s works but this new recording illustrates that it is high time Arianna’s reputation was restored.

The cocky villain Tauride, who spends the opera spouting off at Teseo, opens proceedings with ‘Mirami’ (a marvellous portrayal of swaggering arrogance, not quite captured by the Orchestra of Patras’s elegant phrasing but sung resolutely by Marita Paparizou) and the spectacular ‘Qual leon’ (featuring two magnificent horns, although it is rushed a fraction here). The secondary lovers Carilda and Alceste get a few impressive scenes too, especially Alceste’s sublime ‘Son qual stanco pellegrino’ with a mellifluous cello solo (the soprano castrato Carlo Scalzi might have stolen the show with this in 1734). Soprano Mata Katsuli delivers Arianna’s taxing arias with sensitivity.

However, the towering figure of the opera is Mary-Ellen Nesi’s heroic Teseo. This was the first role Handel composed for the star castrato Carestini and every aria is a gem: ‘Nel pugnar’ is an extensive florid showpiece; sentimental reconciliation is tenderly expressed in ‘Sdegnata sei con me’; and Handel rises to the challenge of the Minotaur scene with a stirring accompanied recitative and a dashing heroic aria (‘Quì ti sfido’).

George Petrou has a firm grasp on Handelian style and presents a persuasive case for the opera’s merits. Overall, this is a more consistent and convincing performance than Nicholas McGegan’s live recording available to members of the Göttingen Handel Society. The predominantly Greek cast and period-instrument orchestra will not be familiar to many but, despite some approximate orchestral intonation, they reveal that Arianna in Creta is well worth investigation. -- David Vickers, Gramophone

Handel’s opera portrays Theseus’ love affair with the Cretan King Minos’ daughter Ariadne, the hero’s victory over the Minotaur, and his escape from the labyrinth. It ends happily, with the sentiment that love overcomes cruelty. None of the later dejection when Ariadne is forsaken on Naxos is portrayed.

Curiously, Porpora and the ‘Opera of the Nobility’ organised Arianna in Nasso at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on December 29, 1733, just under a month before Handel’s treatment of the Theseus and Ariadne story could make it to the King’s Theatre stage. However, Handel’s opera was a much greater success, notching up 16 performances and earning a prompt revival at the beginning of the following season. Produced between Orlando and Ariodante, Arianna in Creta does not quite match the pinnacles that surround it in the chronology of Handel’s works but this new recording illustrates that it is high time Arianna’s reputation was restored.

The cocky villain Tauride, who spends the opera spouting off at Teseo, opens proceedings with ‘Mirami’ (a marvellous portrayal of swaggering arrogance, not quite captured by the Orchestra of Patras’s elegant phrasing but sung resolutely by Marita Paparizou) and the spectacular ‘Qual leon’ (featuring two magnificent horns, although it is rushed a fraction here). The secondary lovers Carilda and Alceste get a few impressive scenes too, especially Alceste’s sublime ‘Son qual stanco pellegrino’ with a mellifluous cello solo (the soprano castrato Carlo Scalzi might have stolen the show with this in 1734). Soprano Mata Katsuli delivers Arianna’s taxing arias with sensitivity.

However, the towering figure of the opera is Mary-Ellen Nesi’s heroic Teseo. This was the first role Handel composed for the star castrato Carestini and every aria is a gem: ‘Nel pugnar’ is an extensive florid showpiece; sentimental reconciliation is tenderly expressed in ‘Sdegnata sei con me’; and Handel rises to the challenge of the Minotaur scene with a stirring accompanied recitative and a dashing heroic aria (‘Quì ti sfido’).

George Petrou has a firm grasp on Handelian style and presents a persuasive case for the opera’s merits. Overall, this is a more consistent and convincing performance than Nicholas McGegan’s live recording available to members of the Göttingen Handel Society. The predominantly Greek cast and period-instrument orchestra will not be familiar to many but, despite some approximate orchestral intonation, they reveal that Arianna in Creta is well worth investigation. -- David Vickers, Gramophone

Related Releases:

![Tim Richards - Tim Richards Hextet Telegraph Hill (2018) [Hi-Res] Tim Richards - Tim Richards Hextet Telegraph Hill (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766996852_rqnxdiia2f5nc_600.jpg)