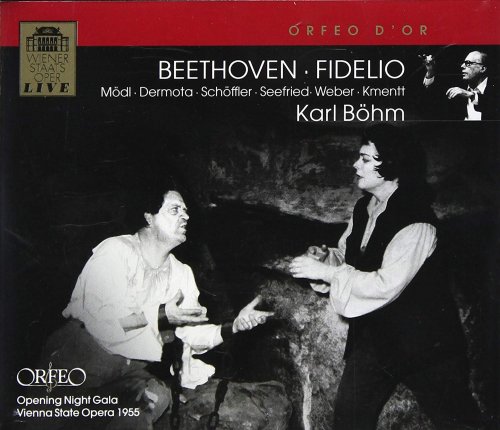

Karl Böhm - Beethoven: Fidelio (2010)

Artist: Karl Böhm

Title: Beethoven: Fidelio

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: Orfeo D'or

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, artwork)

Total Time: 2:07:49

Total Size: 409 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Beethoven: Fidelio

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: Orfeo D'or

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, artwork)

Total Time: 2:07:49

Total Size: 409 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

CD1

1. Ouvertüre

Act 1

2. Duett. Jetzt Schätzchen, jetzt sind wir allein

3. Dialog und Arie. Fidelio... O wär' ich schon mit dir vereint

4. Dialog. Marzelline! Ist Fidelio noch nicht zurück?

5. Quartett. Mir ist so wunderbar

6. Dialog. Höre, Fidelio!

7. Terzett. Gut, Söhnchen, gut, hab' immer Mut

8. Marsch

9. Arie. Hat Welch ein Augenblick!

10. Fidelio, opera, Op. 72: Act 1. Dialog. Rocco! Die Depeschen!

11. Duett. Jetzt, Alter, hat es Elle!

12. Rezitativ und Arie. Abscheulicher!... Komm, Hoffnung, laß den letzten Stern

13. Dialog. Rocco! Ich ersuchte Euch

14. Finale. O welche Lust

15. Finale. Nun sprecht, wie ging's

16. Finale. Ach Vater, eilt!... Verweg'ner Alter!

17. Finale. Leb wohl, du warmes Sonnenlicht

CD2

Act 2

1. Orchestervorspiel, Rezitativ und Arie. Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!... In des Lebens Frühlingsta

2. Melodram und Duett. Wie kalt ist es... Nur hurtig fort, nur frisch gegraben

3. Dialog. Er erwacht!

4. Terzett. Euch werde Lohn in besser'n Welten

5. Dialog. Ich geh'

6. Quartett. Er sterbe!... Es schlägt der Rache Stunde

7. Dialog und Duett. Leonore!... O namenlose Freude!

8. Leonoren-Ouvertüre No. 3, Op. 72a

9. Finale. Heil sei dem Tag

10. Finale. Des besten Königs Wink und Wille

11. Finale. Wer ein holdes Weib errungen

“The immediacy of expression, the dramatic tension and the vitality achieved not only by the singers but also by the full-throated chorus, the wonderful orchestra and, last but not least, Karl Böhm himself all set standards by which other performances must be judged and found wanting.” So sayeth the liner notes to this first official release of the original broadcast tapes of the Fidelio that reopened the Vienna State Opera in 1955. While I agree that the dramatic tension is there, I do not believe it is “found wanting” in all other performances. The Metropolitan Opera broadcast of February 1941, with Kirsten Flagstad, Marta Farell, René Maison, and Alexander Kipnis, conducted by Bruno Walter, also has a similar tension, as does Böhm’s magnificent and highly underrated 1968 commercial recording and the Met broadcast of January 7, 1980, with Marton, Peters, Vickers, and Plishka, conducted by Klaus Tennstedt. Where it is not palpable is in the overrated 1961 EMI studio recording with Ludwig, Vickers, and Klemperer, but that is another story.

That being said, there is no question that Martha Mödl throws herself into the role of Leonore in a way that gives an undercurrent of tension, even to the spoken recitatives. From the first, she sounds like a woman on the edge, so highly wound up that she is on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Unfortunately, this same edginess that gives her performances dramatic veracity also afflicts her singing. From the entrance of the horns in the stretta section of the “Abscheulischer” to the end, she is pushing the voice far too hard, which leads to a strident final high note, and in the confrontation scene with Pizarro in act II her high note is less than that, merely a scream. On the other hand, I’ve never heard any soprano sustain so much drama in the voice and phrase continuously as she does in the trio “Gut, Sönchen, gut,” and earlier in the “Abscheulischer” her voice assumes almost the identical color and timbre as Lilli Lehmann in her 1906 recording.

Paul Schöffler is his usual excellent self as Pizarro and Weber’s dark tone uncannily resembles Gottlob Frick in more than a few moments. Anton Dermota, a famed Mozart tenor who sang Florestan for the first time here, captures the character much better than in his broadcast performance (c.1946) of “Gott, welch dunkel hier.” Many of his dramatic accents, and the way he interprets the text, remind me of Jon Vickers, though one must remember that this is before Vickers ever sang the role. Waldemar Kmentt pares down his large voice to sing a splendid Jacquino, and Irmgard Seefried is absolutely sparkling as Marzelline.

Böhm’s conducting here is curious. Although one hears a full-bodied sound in the basses and percussion, the upper strings sound particularly bright and lean, almost as though he were leading a stripped-down orchestra to the dimensions of Beethoven’s time. He creates a wonderfully dark mood for the opera, as he usually did, but in some instances his tempos are slower than on his commercial recording. He compensates for this slowness by introducing accelerandi at the end of arias and duets. I’m sure this was effective in the theater, but on a record where you can hear it again and again I can see where it would become wearing. Following a Viennese tradition that went back to Mahler, he inserts the Leonore Overture No. 3 into the second act (Walter and Tennstedt did the same), but arbitrarily cuts Rocco’s first-act aria, “Hat man nicht auch Gold beneiben.” The violins sound unexpectedly ragged in the middle of the Leonore No. 3, but otherwise, the orchestra plays very well and the chorus is excellent.

As mentioned, the sound is broadcast mono quality, the orchestra more clearly recorded than the singers. Every time a singer is at the back of the stage the voice is recessed (as is Mödl in the opening lines of “Abscheulischer”), and even when forward the resonance of the theater tends to dull the ring of the voices. Taking all things into consideration, it is indeed interesting to hear this Fidelio for Böhm’s lean string sound and the intensity of Mödl’s Leonore, but I’d only recommend this as a third or fourth Fidelio, never a first choice. -- FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

That being said, there is no question that Martha Mödl throws herself into the role of Leonore in a way that gives an undercurrent of tension, even to the spoken recitatives. From the first, she sounds like a woman on the edge, so highly wound up that she is on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Unfortunately, this same edginess that gives her performances dramatic veracity also afflicts her singing. From the entrance of the horns in the stretta section of the “Abscheulischer” to the end, she is pushing the voice far too hard, which leads to a strident final high note, and in the confrontation scene with Pizarro in act II her high note is less than that, merely a scream. On the other hand, I’ve never heard any soprano sustain so much drama in the voice and phrase continuously as she does in the trio “Gut, Sönchen, gut,” and earlier in the “Abscheulischer” her voice assumes almost the identical color and timbre as Lilli Lehmann in her 1906 recording.

Paul Schöffler is his usual excellent self as Pizarro and Weber’s dark tone uncannily resembles Gottlob Frick in more than a few moments. Anton Dermota, a famed Mozart tenor who sang Florestan for the first time here, captures the character much better than in his broadcast performance (c.1946) of “Gott, welch dunkel hier.” Many of his dramatic accents, and the way he interprets the text, remind me of Jon Vickers, though one must remember that this is before Vickers ever sang the role. Waldemar Kmentt pares down his large voice to sing a splendid Jacquino, and Irmgard Seefried is absolutely sparkling as Marzelline.

Böhm’s conducting here is curious. Although one hears a full-bodied sound in the basses and percussion, the upper strings sound particularly bright and lean, almost as though he were leading a stripped-down orchestra to the dimensions of Beethoven’s time. He creates a wonderfully dark mood for the opera, as he usually did, but in some instances his tempos are slower than on his commercial recording. He compensates for this slowness by introducing accelerandi at the end of arias and duets. I’m sure this was effective in the theater, but on a record where you can hear it again and again I can see where it would become wearing. Following a Viennese tradition that went back to Mahler, he inserts the Leonore Overture No. 3 into the second act (Walter and Tennstedt did the same), but arbitrarily cuts Rocco’s first-act aria, “Hat man nicht auch Gold beneiben.” The violins sound unexpectedly ragged in the middle of the Leonore No. 3, but otherwise, the orchestra plays very well and the chorus is excellent.

As mentioned, the sound is broadcast mono quality, the orchestra more clearly recorded than the singers. Every time a singer is at the back of the stage the voice is recessed (as is Mödl in the opening lines of “Abscheulischer”), and even when forward the resonance of the theater tends to dull the ring of the voices. Taking all things into consideration, it is indeed interesting to hear this Fidelio for Böhm’s lean string sound and the intensity of Mödl’s Leonore, but I’d only recommend this as a third or fourth Fidelio, never a first choice. -- FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Related Releases:

![Tõnu Naissoo - Nordic Suite (2026) [Hi-Res] Tõnu Naissoo - Nordic Suite (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/27/9so2z3ab1rjo0qkgwhwre1np0.jpg)