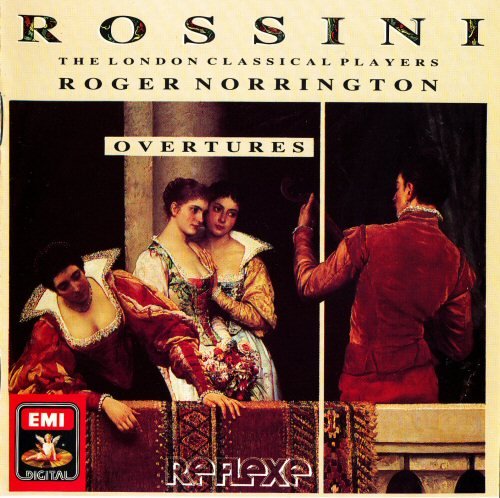

Roger Norrington - Rossini Overtures (1991)

Artist: Roger Norrington

Title: Rossini Overtures

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: EMI Records Ltd

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 1:00:24

Total Size: 242 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Rossini Overtures

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: EMI Records Ltd

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 1:00:24

Total Size: 242 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. La scala di seta (Allegro vivace - Andantino - Allegro)

02. Il signor Bruschino (Allegro)

03. L'Italiana in Algieri (Andante - Allegro)

04. Il barbiere di Siviglia (Andante maestoso - Allegro con brio - Più mosso)

05. La gazza ladra (Maestoso marziale - [Allegro] - Più mosso)

06. Semiramide (Allegro vivace - Andantino - Allegro)

07. Guillaume Tell (Andante - Allegro - Andantino - Allegro vivace)

Review by Richard Osborne, The Gramophone

Roger Norrington is a man who has smelt grease-paint in his time. Before he became the urbane megastar of the international period-instrument circuit, he plied his trade, figuratively speaking, in the opera pit—though being Norrington he invariably rejoiced in the fact that many of the venues visited by Kent Opera in its halcyon years were bereft of those subterranean dungeons that do nothing but harm to the interplay of voices and orchestra in the operas of Mozart and Rossini. In fact, the Rossini revival was in its infancy in the 1970s and I don't recall Norrington bringing his forensic genius to bear in the theatre on anything other than Il barbiere di Siviglia.

So, this disc of Rossini overtures hints at what might have been. In the event, it is perhaps the cheekiest, most shocking, most uproarious, and in some ways the most revelatory collection of Rossini overtures yet put on record. It is not, though, a record for the knit-two pearl-two sisterhood or for lovers of Muzak or for those in search of a quiet time. The spiritual descendants of Rossini's contemporary foe, Lord Mount-Edgcumbe, will grimace at the very sound of it and may even hold up perfectly manicured hands in wan gestures of dismay. ''Who is this brute?'' they will ask of Norrington as they asked of Rossini all those years ago.

We forget nowadays that Rossini was a contemporary of Beethoven and that his music was considered by dilettantes and followers of Paisiello to be appallingly noisy. Even I had forgotten how noisy it can be until Norrington and his merry men bludgeoned me out of my study with the L'italiana coda and then sent me reeling—expletive deleted—with a really murderous thwack on the drum at the end of the Overture to Il barbiere. Re-creating Rossini's capacity to shock and disturb to this degree is the work of a true Authenticke.

In fact, the Overture to Il barbiere is wonderfully well characterized here. It reeks of feminine wiles, of storms and backstairs conspiracy. And if you think this so much critical moonshine given the fact that this is the overture's third incarnation, I would submit that such an argument offers the real moonshine. The secret of this particular overture is that it was born to preface Il barbiere and, once there, it has found it the easiest thing in the world retrospectively to absorb the opera's variegated moods.

Of course, we expect high drama in some of the later overtures. La gazza ladra's is magnificently done here with the wide stereophonic disposition of the side-drums not only making a terrific effect at the start but also adding colour and real drama to the famous crescendo sequence. I thought Norrington's way with the main allegro material of the Semiramide Overture curiously underpowered (no one has ever equalled Toscanini in this piece). This is particularly disappointing after the hair-raising drum-led opening onrush and the fabulous period-instrument brass sonorities in the Andantino where the supporting voices and chords etch into the music a real sense of menace, as though Assur, the Iago-figure, is there lurking in the shadows.

Once or twice the old instruments, the natural horns in particular, bellow and burb uncontrollably; but this is all part of the fun and it is no worse, I suspect, than the kind of thing Rossini would have heard in Senigallia or Rome or even, occasionally, from the virtuosos of the San Carlo orchestra in Naples. By and large, the wind playing is a joy. In the Overture to La scala di seta the soloists emerge as an unstoppable gaggle of egregious gossips. Beecham's famous 1933 Columbia recording (nla) sounds tame by comparison. Indeed, I don't recall a wind section bitching—musically speaking— quite as virulently as this one, though there is an old Philharmonia recording of the Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka under Karajan that runs it close. Modern strings can sometimes make an icier sul ponticello effect than Norrington's players do but modern winds cannot match the kind of sound we get here from horns, from the crusty Rumpole-like bassoons, or even the oboes.

Indeed, one of the primary delights of the disc is the astonishing array of fleeting instrumental asides that are usually muted in latter-day performances—a flute briefly cooing in the background or a sudden sharp sting of muted brass tone. The recapitulation of the second subject in the L'italiana Overture is always a wonderful moment, piccolo and bassoon coming together like Laurel and Hardy (track 3 at 6'13'') but I've never heard the oboe's riposte five seconds later sound so scabrous. In the Overture to Il Signor Bruschino the dramatically played bow-taps seem to be on wooden stands rather than metal candle-holders. Presumably the latter are not easy to come by, even in St John's Wood where EMI's splendidly buxom recordings were made. Like Scimone in his complete recording for Erato (3/81—nla), Norrington goes to town with the Banda Turca in L'italiana. Perhaps it is too much of a good thing; on the other hand, it is good to have a distinctly audible triangle in the pastoral section of a finely played account of the Guillaume Tell Overture.

It is also good to have the overtures presented in chronological order. Not the least of the drawbacks of many Rossini overture discs is their philistine disregard for a running-order that is based either on key sequences or chronology. Marriner's 1989 EMI disc was a prime offender in this respect with Guillaume Tell plonked down in the middle of the disc immediately before an apprentice piece of 1810.

A rival collection has recently come from that master Rossinian, Claudio Abbado, with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. That may well give us clearer sense of Rossini the urbane wit and classical stylist. What no one is likely to do in the foreseeable future is to upset the Rossini apple-cart quite as spectacularly as Norrington and his players do in this uncomfortable—and richly revelatory—new disc.'

Roger Norrington is a man who has smelt grease-paint in his time. Before he became the urbane megastar of the international period-instrument circuit, he plied his trade, figuratively speaking, in the opera pit—though being Norrington he invariably rejoiced in the fact that many of the venues visited by Kent Opera in its halcyon years were bereft of those subterranean dungeons that do nothing but harm to the interplay of voices and orchestra in the operas of Mozart and Rossini. In fact, the Rossini revival was in its infancy in the 1970s and I don't recall Norrington bringing his forensic genius to bear in the theatre on anything other than Il barbiere di Siviglia.

So, this disc of Rossini overtures hints at what might have been. In the event, it is perhaps the cheekiest, most shocking, most uproarious, and in some ways the most revelatory collection of Rossini overtures yet put on record. It is not, though, a record for the knit-two pearl-two sisterhood or for lovers of Muzak or for those in search of a quiet time. The spiritual descendants of Rossini's contemporary foe, Lord Mount-Edgcumbe, will grimace at the very sound of it and may even hold up perfectly manicured hands in wan gestures of dismay. ''Who is this brute?'' they will ask of Norrington as they asked of Rossini all those years ago.

We forget nowadays that Rossini was a contemporary of Beethoven and that his music was considered by dilettantes and followers of Paisiello to be appallingly noisy. Even I had forgotten how noisy it can be until Norrington and his merry men bludgeoned me out of my study with the L'italiana coda and then sent me reeling—expletive deleted—with a really murderous thwack on the drum at the end of the Overture to Il barbiere. Re-creating Rossini's capacity to shock and disturb to this degree is the work of a true Authenticke.

In fact, the Overture to Il barbiere is wonderfully well characterized here. It reeks of feminine wiles, of storms and backstairs conspiracy. And if you think this so much critical moonshine given the fact that this is the overture's third incarnation, I would submit that such an argument offers the real moonshine. The secret of this particular overture is that it was born to preface Il barbiere and, once there, it has found it the easiest thing in the world retrospectively to absorb the opera's variegated moods.

Of course, we expect high drama in some of the later overtures. La gazza ladra's is magnificently done here with the wide stereophonic disposition of the side-drums not only making a terrific effect at the start but also adding colour and real drama to the famous crescendo sequence. I thought Norrington's way with the main allegro material of the Semiramide Overture curiously underpowered (no one has ever equalled Toscanini in this piece). This is particularly disappointing after the hair-raising drum-led opening onrush and the fabulous period-instrument brass sonorities in the Andantino where the supporting voices and chords etch into the music a real sense of menace, as though Assur, the Iago-figure, is there lurking in the shadows.

Once or twice the old instruments, the natural horns in particular, bellow and burb uncontrollably; but this is all part of the fun and it is no worse, I suspect, than the kind of thing Rossini would have heard in Senigallia or Rome or even, occasionally, from the virtuosos of the San Carlo orchestra in Naples. By and large, the wind playing is a joy. In the Overture to La scala di seta the soloists emerge as an unstoppable gaggle of egregious gossips. Beecham's famous 1933 Columbia recording (nla) sounds tame by comparison. Indeed, I don't recall a wind section bitching—musically speaking— quite as virulently as this one, though there is an old Philharmonia recording of the Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka under Karajan that runs it close. Modern strings can sometimes make an icier sul ponticello effect than Norrington's players do but modern winds cannot match the kind of sound we get here from horns, from the crusty Rumpole-like bassoons, or even the oboes.

Indeed, one of the primary delights of the disc is the astonishing array of fleeting instrumental asides that are usually muted in latter-day performances—a flute briefly cooing in the background or a sudden sharp sting of muted brass tone. The recapitulation of the second subject in the L'italiana Overture is always a wonderful moment, piccolo and bassoon coming together like Laurel and Hardy (track 3 at 6'13'') but I've never heard the oboe's riposte five seconds later sound so scabrous. In the Overture to Il Signor Bruschino the dramatically played bow-taps seem to be on wooden stands rather than metal candle-holders. Presumably the latter are not easy to come by, even in St John's Wood where EMI's splendidly buxom recordings were made. Like Scimone in his complete recording for Erato (3/81—nla), Norrington goes to town with the Banda Turca in L'italiana. Perhaps it is too much of a good thing; on the other hand, it is good to have a distinctly audible triangle in the pastoral section of a finely played account of the Guillaume Tell Overture.

It is also good to have the overtures presented in chronological order. Not the least of the drawbacks of many Rossini overture discs is their philistine disregard for a running-order that is based either on key sequences or chronology. Marriner's 1989 EMI disc was a prime offender in this respect with Guillaume Tell plonked down in the middle of the disc immediately before an apprentice piece of 1810.

A rival collection has recently come from that master Rossinian, Claudio Abbado, with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. That may well give us clearer sense of Rossini the urbane wit and classical stylist. What no one is likely to do in the foreseeable future is to upset the Rossini apple-cart quite as spectacularly as Norrington and his players do in this uncomfortable—and richly revelatory—new disc.'

![Paul Desmond - Complete Quartet Recordings with Jim Hall [4CD] (2022) Paul Desmond - Complete Quartet Recordings with Jim Hall [4CD] (2022)](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770567500_pltny8nj8icra_600.jpg)

![Oulu All Star Big Band, Ingá-Máret Gaup-Juuso and Jukka Eskola - Davvi Oktavuohta - Pohjoinen yhteys (2026) [Hi-Res] Oulu All Star Big Band, Ingá-Máret Gaup-Juuso and Jukka Eskola - Davvi Oktavuohta - Pohjoinen yhteys (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770364798_k6yo0dxz10jkv_600.jpg)