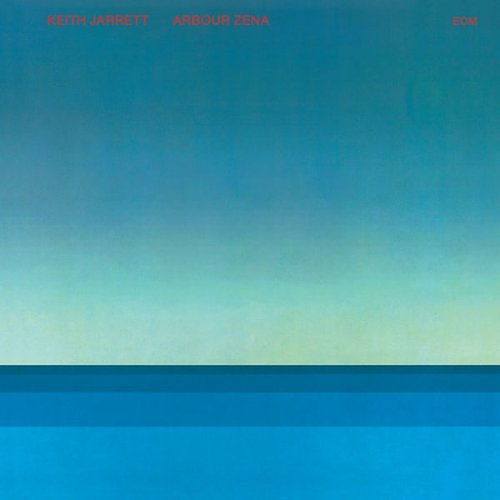

Keith Jarrett - Arbour Zena (2015) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Keith Jarrett

Title: Arbour Zena

Year Of Release: 1975 / 2015

Label: ECM Records

Genre: Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks, booklet) [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 53:00

Total Size: 1.01 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Arbour Zena

Year Of Release: 1975 / 2015

Label: ECM Records

Genre: Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks, booklet) [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 53:00

Total Size: 1.01 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

1 Runes (15:20)

2 Solara March (9:40)

3 Mirrors (27:47)

“I consider this one of my most richly lyrical and consistently inspired works,” wrote Keith Jarrett of “Mirrors”, the almost half-hour long concluding piece on Arbour Zena. “Jan Garbarek’s contribution is irreplaceable and ecstatic.” It is easy to agree that Arbour Zena as a whole is one of Jarrett’s most exceptional albums. Evocative writing for strings, beautiful playing by Keith and Jan and by Charlie Haden at his most soulful, and a glowing panoramic production make this 1975 recording one of the finest of the early ECMs.

The moment I lie in bed and begin listening to this album in my dorm room for the purposes of this review, my suitemate launches into a volatile argument with his girlfriend. As their loud verbal match breaches the gap under my door, I trace its implications across the geography of Arbour Zena. I think about the fallibility of relationships, about the trials and rewards of a musical life, and about the often contrived ways in which we attempt to validate our own experiences through the art of others.

Against a backdrop of accusations of infidelity, “Runes” blooms to quiet life with a slow orchestral tremolo. Jarrett disturbs the crystalline stillness with shafts of light and the bass falls like thick droplets as the orchestra turns to the morning sun, treading lightly upon the water so as not to disrupt its surface tension. The piano fades, leaving Haden to amble along the banks, skirting the limits of our visible world. Jarrett returns as if back from a foraging expedition, peering carefully into the scene laid before us as he unfurls a background of epic dimensions. He then pulls the orchestra in a new direction, leaving the bass to contemplate the fate of its own path. At first, we aren’t sure if the two are even connected. Perhaps they will join again, we wonder. Jarrett’s intimate piano improvisations dip their toes into waters familiar to fans of his solo work. Yet for all the music’s scope, we don’t so much travel as burrow deeper into the recesses of indecision until Garbarek’s entrance wakes us. In its own strange way, the music does resolve itself as these disparate voices achieve harmony over time. Where Luminessence was a conversation, “Runes” feels more like a narrative that jumps from one character’s head to another. It is also very difficult to picture the music, for Jarrett works in emotions here rather than in images. These aren’t simply the antagonistic ramblings of a polemicist, but rather the careful scripts of one whose relationship to determinacy is as complex as life itself, fragile as the flutter of breath over reed that ends the piece.

“Solara March” draws its plaintive curtains back to reveal an orchestra and bass. This is but the preamble to some stunning passages in which the piano touches off a lush tripping of orchestral sound while the bass seems only to meander, as if content to face an oncoming storm. As Jarrett plays a linear melody on the keyboard’s higher register, the bass continues to murmur in the background, as if unaware of its own critical potential. Garbarek injects some liveliness halfway through the “March.” With a characteristic buoyancy, Jarrett nudges us toward an opulent climax. The music finds its stride and renders worthwhile our disjointed path to getting there.

The third and final piece, entitled “Mirrors,” reflects a keening orchestral introduction, segueing into an extended meditation for piano and strings. As improviser over his own orchestral writing, Jarrett draws from the same threads and with the same colors, whereas his other improvisers mix their hues on an entirely different palette, if on the same canvas. With Jarrett leading the way, Garbarek has a much easier time fitting into the constantly shifting puzzle of the former’s evocative presence: the din of a distant flock of birds conveyed by the wind from an unseen field, or perhaps the sound of waves flitting in and out of our audible range. The lack of bass here is somehow comforting, leaving Jarrett and Garbarek to glide ever more assuredly across the album’s opaque surface. During this movement my suitemate’s girlfriend shouts, “That’s it! We’re through,” leaving behind not only a silent partner, but also emptiness in what would otherwise be a Saturday evening filled with laughter and sounds of lovemaking bleeding through these hollow walls.

This album is strangely recorded. The orchestra is given very little breathing room while Haden stands aloof, sounding as if he were recorded in a separate room and eased in later at the mixing board. In many ways, the bass is our mediator, our interpreter between languages and worlds, operating as it does a subliminal space. The music on Arbour Zena is diffuse, composed of blurry snatches of memory. There is nothing incredibly arresting about it. It doesn’t invite the listener and only barely acknowledges that it is being heard, playing not even for itself. It is like a dance missing a few steps, a garden with a trampled flowerbed and only a few unblemished specimens holding fast to their roots. It is the liberation of desire from the trappings of its own desire to be desired. Jarrett’s fellow musicians are rather well suited to this project, for to provide such continual commentary must be a challenge to even the most skilled.

Since writing this review, I am happy to report that my suitemate and his girlfriend have gotten back together, and I have taken to listening to Arbour Zena anew as an expression of hope—a musical talisman of emotional harmony in an unsympathetic world.

Keith Jarrett, piano

Jan Garbarek, soprano and tenor saxophones

Charlie Haden, double bass

String Orchestra (Members of the Radio Symphony Orchestra, Stuttgart)

Mladen Gutesha, conductor

Recorded October 1975 at Studio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineered by Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Digitally remastered by ECM.

The moment I lie in bed and begin listening to this album in my dorm room for the purposes of this review, my suitemate launches into a volatile argument with his girlfriend. As their loud verbal match breaches the gap under my door, I trace its implications across the geography of Arbour Zena. I think about the fallibility of relationships, about the trials and rewards of a musical life, and about the often contrived ways in which we attempt to validate our own experiences through the art of others.

Against a backdrop of accusations of infidelity, “Runes” blooms to quiet life with a slow orchestral tremolo. Jarrett disturbs the crystalline stillness with shafts of light and the bass falls like thick droplets as the orchestra turns to the morning sun, treading lightly upon the water so as not to disrupt its surface tension. The piano fades, leaving Haden to amble along the banks, skirting the limits of our visible world. Jarrett returns as if back from a foraging expedition, peering carefully into the scene laid before us as he unfurls a background of epic dimensions. He then pulls the orchestra in a new direction, leaving the bass to contemplate the fate of its own path. At first, we aren’t sure if the two are even connected. Perhaps they will join again, we wonder. Jarrett’s intimate piano improvisations dip their toes into waters familiar to fans of his solo work. Yet for all the music’s scope, we don’t so much travel as burrow deeper into the recesses of indecision until Garbarek’s entrance wakes us. In its own strange way, the music does resolve itself as these disparate voices achieve harmony over time. Where Luminessence was a conversation, “Runes” feels more like a narrative that jumps from one character’s head to another. It is also very difficult to picture the music, for Jarrett works in emotions here rather than in images. These aren’t simply the antagonistic ramblings of a polemicist, but rather the careful scripts of one whose relationship to determinacy is as complex as life itself, fragile as the flutter of breath over reed that ends the piece.

“Solara March” draws its plaintive curtains back to reveal an orchestra and bass. This is but the preamble to some stunning passages in which the piano touches off a lush tripping of orchestral sound while the bass seems only to meander, as if content to face an oncoming storm. As Jarrett plays a linear melody on the keyboard’s higher register, the bass continues to murmur in the background, as if unaware of its own critical potential. Garbarek injects some liveliness halfway through the “March.” With a characteristic buoyancy, Jarrett nudges us toward an opulent climax. The music finds its stride and renders worthwhile our disjointed path to getting there.

The third and final piece, entitled “Mirrors,” reflects a keening orchestral introduction, segueing into an extended meditation for piano and strings. As improviser over his own orchestral writing, Jarrett draws from the same threads and with the same colors, whereas his other improvisers mix their hues on an entirely different palette, if on the same canvas. With Jarrett leading the way, Garbarek has a much easier time fitting into the constantly shifting puzzle of the former’s evocative presence: the din of a distant flock of birds conveyed by the wind from an unseen field, or perhaps the sound of waves flitting in and out of our audible range. The lack of bass here is somehow comforting, leaving Jarrett and Garbarek to glide ever more assuredly across the album’s opaque surface. During this movement my suitemate’s girlfriend shouts, “That’s it! We’re through,” leaving behind not only a silent partner, but also emptiness in what would otherwise be a Saturday evening filled with laughter and sounds of lovemaking bleeding through these hollow walls.

This album is strangely recorded. The orchestra is given very little breathing room while Haden stands aloof, sounding as if he were recorded in a separate room and eased in later at the mixing board. In many ways, the bass is our mediator, our interpreter between languages and worlds, operating as it does a subliminal space. The music on Arbour Zena is diffuse, composed of blurry snatches of memory. There is nothing incredibly arresting about it. It doesn’t invite the listener and only barely acknowledges that it is being heard, playing not even for itself. It is like a dance missing a few steps, a garden with a trampled flowerbed and only a few unblemished specimens holding fast to their roots. It is the liberation of desire from the trappings of its own desire to be desired. Jarrett’s fellow musicians are rather well suited to this project, for to provide such continual commentary must be a challenge to even the most skilled.

Since writing this review, I am happy to report that my suitemate and his girlfriend have gotten back together, and I have taken to listening to Arbour Zena anew as an expression of hope—a musical talisman of emotional harmony in an unsympathetic world.

Keith Jarrett, piano

Jan Garbarek, soprano and tenor saxophones

Charlie Haden, double bass

String Orchestra (Members of the Radio Symphony Orchestra, Stuttgart)

Mladen Gutesha, conductor

Recorded October 1975 at Studio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineered by Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Digitally remastered by ECM.

![Ex Novo Ensemble - Claudio Ambrosini: Chamber Music (2020) [Hi-Res] Ex Novo Ensemble - Claudio Ambrosini: Chamber Music (2020) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/22/z541qb9ul4q390uxlw1d9iak3.jpg)