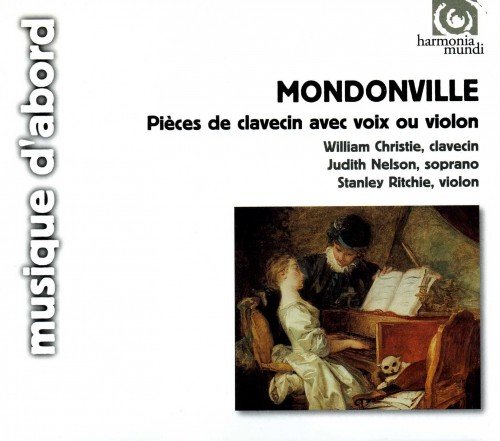

William Christie, Judith Nelson & Stanley Ritchie - Mondonville: Pieces de clavecin avec voix ou violon (2008)

Artist: William Christie, Judith Nelson, Stanley Ritchie

Title: Mondonville: Pieces de clavecin avec voix ou violon

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks + .cue)

Total Time: 52:52 min

Total Size: 314 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Mondonville: Pieces de clavecin avec voix ou violon

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks + .cue)

Total Time: 52:52 min

Total Size: 314 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Regna terrae, Cantate Deo

2. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: In decachordo psalterio

3. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Benefac, Domine

4. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Laudate Dominum

5. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Paratum cor meum

6. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: In Domino laudabitur

7. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Quare tristis es, anima mea

8. Pieces de clavecin, violon ou voix, Op. 5: Protector meus

Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville, although little known, was much less of a petitmaître than Boismortier or Michel Corrette, for instance. Born in 1711, he occupied quite an important place in early eighteenth-century French musical life. He was a fine violinist, a successful composer of church music and an active personality in the "Concerts Spirituels", public concerts which became established in Paris in 1725. Most of his chamber music belongs to the first half of the eighteenth century—his harpsichord sonatas with violin accompaniment (Op. 3, cl 734) are examples of an individuality of mind—and these eight Pièces de Clavecin at'ec Voix ou Violon (Op. 5) were published in 1748. After that, Mondonville composed almost entirely for the Paris Opéra, so his Op. 5 appear to be his last pieces of chamber music.

The harpsichord works with voice or violin recorded here display no less individuality than Mondonville's Op. 3 Sonatas; in fact they are, if anything bolder though perhaps, in the end, the interest lies more in their singularity than in their intrinsic musical worth. Two forms predominate here, rondeau and aria dal segna, and there is also a fairly well defined distinction between Italian and French styles. Mondonville is happier with the rondeau, I think, and this can be readily heard in the engaging "Benefac Domine" which evokes most delicately the rococo taste and manners of the period. Whether or not he added the words to existing music or whether he composed these pieces with such a combination in mind is open to question; the idea is so experimental that we might forgive him the occasional lapsus sub.

Judith Nelson sings with sensitivity though with less assurance than I usually associate with her; intonation is a little shaky in places, and the same goes for the violinist, Stanley Ritchie, whose contribution in other respects is admirable. William Christie is excellent. Despite this small criticism I enjoyed this musical backwater enormously; some or the melodies are haunting and no-one with a taste for Messrs Duphly or Balbastre should miss the "Benefac Domine", or indeed the "Protector meus" which has a ritornello curiously reminiscent of an Albinoni oboe concerto (Op. 9 No. It in B flat. I think!). Fascinating. -- Gramophone

The harpsichord works with voice or violin recorded here display no less individuality than Mondonville's Op. 3 Sonatas; in fact they are, if anything bolder though perhaps, in the end, the interest lies more in their singularity than in their intrinsic musical worth. Two forms predominate here, rondeau and aria dal segna, and there is also a fairly well defined distinction between Italian and French styles. Mondonville is happier with the rondeau, I think, and this can be readily heard in the engaging "Benefac Domine" which evokes most delicately the rococo taste and manners of the period. Whether or not he added the words to existing music or whether he composed these pieces with such a combination in mind is open to question; the idea is so experimental that we might forgive him the occasional lapsus sub.

Judith Nelson sings with sensitivity though with less assurance than I usually associate with her; intonation is a little shaky in places, and the same goes for the violinist, Stanley Ritchie, whose contribution in other respects is admirable. William Christie is excellent. Despite this small criticism I enjoyed this musical backwater enormously; some or the melodies are haunting and no-one with a taste for Messrs Duphly or Balbastre should miss the "Benefac Domine", or indeed the "Protector meus" which has a ritornello curiously reminiscent of an Albinoni oboe concerto (Op. 9 No. It in B flat. I think!). Fascinating. -- Gramophone

![Willie Colón - El Baquiné de Angelitos Negros (Remastered 2026) (2026) [Hi-Res] Willie Colón - El Baquiné de Angelitos Negros (Remastered 2026) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/12/cq8tfu6dh9eaj042k3ycd5lv0.jpg)

![Ricardo Ribeiro - A Alma Só Está Bem Onde Não Cabe (2026) [Hi-Res] Ricardo Ribeiro - A Alma Só Está Bem Onde Não Cabe (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/12/wncr8qeaew3niwkr96kcidaf3.jpg)