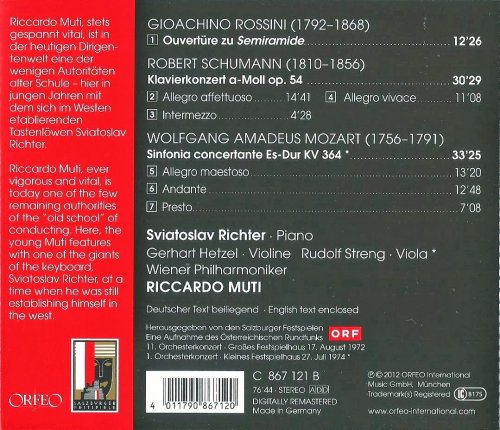

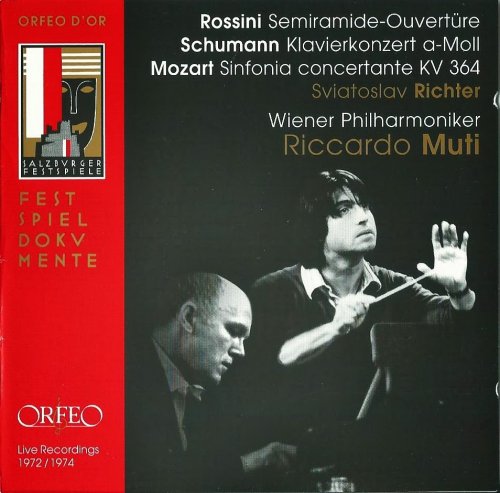

Sviatoslav Richter, Riccardo Muti - Schumann: Piano Concerto, Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante (2012)

Artist: Sviatoslav Richter, Riccardo Muti

Title: Schumann: Piano Concerto, Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Orfeo

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 76:44

Total Size: 385 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Schumann: Piano Concerto, Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Orfeo

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 76:44

Total Size: 385 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Rossini - Overture "Semiramide" [0:12:39.13]

02. Schumann - Piano concerto in A minor - I. Allegro affettuoso [0:14:54.34]

03. Schumann - Piano concerto in A minor - II. Intermezzo [0:04:28.36]

04. Schumann - Piano concerto in A minor - III. Allegro vivace [0:11:15.10]

05. Mozart - Sinfonia concertante in E flat major K 364 - I. Allegro maestoso [0:13:28.71]

06. Mozart - Sinfonia concertante in E flat major K 364 - II. Andante [0:12:48.07]

07. Mozart - Sinfonia concertante in E flat major K 364 - III. Presto [0:07:08.26]

Performers:

Sviatoslav Richter - piano

Gerhart Hetzel - violin

Rudolf Streng - viola

Wiener Philharmoniker

Riccardo Muti - conductor

Orfeo has done it again: The label has released a disc that we should all want. The first two pieces are special indeed, as they mark Riccardo Muti’s conducting debut at the Salzburg Festival, now well over 40 years ago. The year 1972 was special for Muti, as it also marked the very first time he conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra, an ensemble which he would head just a few years later. The Mozart comes from a later appearance, in 1974 recorded at the Kleines Festspielhaus; it replaces the original finale to that debut concert—Cherubini’s Requiem in D Minor—as no recording of it survives. The same way one would describe Muti at his best can already be seen here, when the conductor was but 31 years of age—his approach is dramatic, yet refined in quality; it is intelligent music-making at its finest.

The program begins with Rossini’s Overture to Semiramide . The pacing from the onset is perfect and each section is characterized beautifully. There are particular moments which stand out to me: the reticent yet glowing horn playing near the work’s beginning with its sense of yearning; the delicate sections of string pizzicatos, which gently accompany the winds; and not least of all the grand and climactic ending. It is a fitting way to begin the recital. The Schumann is far different than I expected: Richter’s approach is understated. The pianist, known for his bombastic way in certain works—the Prokofiev Fifth Concerto for example!—plays not the passionate aspects of this work to the fullest, but rather the poetic, idyllic ones. Does Muti or the Vienna Philharmonic have something to do with this approach? Perhaps, though at times I miss the more aggressive aspects of this concerto, especially in the orchestral parts. The Vienna players have a suaveness to them, a beautiful flowing sound—they understand the inherent drama in this music, perhaps because they perform so very many operas—though they are a little less grand in this concerto than, for example, the Berlin Philharmonic under Abbado in Perahia’s recording (Sony 64577). The tempo chosen for the Intermezzo works well in this performance. Again they capture the spirit of the music perfectly. The outer sections are playful, even effervescent in effect, while the central portion’s transparent sound—the vibrato used by the strings adds a special glow to this section—contrasts beautifully with the more lively sections, which frame it. The finale is a bit sluggish at its opening, though the artists push the tempo throughout the movement. Richter’s passagework is crisp and clean; it sparkles at its best. The opening of the Mozart is tender in effect. It is obvious that these players love the work. The soloists in particular seem to breathe every phrase and feel every pause together. And though they play it in a very 19th-century way, sounding a bit heavy in certain places—over the years my ears have become more attuned to the lighter period-practice sound—this is one of those works that can take this type of treatment. The Andante is a bit slower than the norm (anywhere from 0:30 to about 1:00 slower than Perlman/Zukerman, Mutter/Bashmet, or Dumay/Caussé) though the tempo never drags. Remarkably the Vienna Philharmonic knows just when to pull back, creating a cushion of sound on top of which the soloists can gently place their material. The finale provides that necessary breath of fresh air after the two serious movements that it follows. The orchestra is as light here as they were in the Rossini—amazing how consistent their sound can remain after a few years!

Whether one is interested in Muti, in Richter, in the Vienna Philharmonic, in the two phenomenal soloists Hetzel and Streng, in Mozart, Schumann, or Rossini (and how can’t one be in at least one of them?), this is a recording you’ll want in your collection. The energy that each of these phenomenal musicians brings is palpable. The excellent recorded sound, the tiniest amount of audience noise, and the very fine program notes all add to the overall enjoyment of this disc. Grab it and enjoy! Discs like this don’t come around that often.

The program begins with Rossini’s Overture to Semiramide . The pacing from the onset is perfect and each section is characterized beautifully. There are particular moments which stand out to me: the reticent yet glowing horn playing near the work’s beginning with its sense of yearning; the delicate sections of string pizzicatos, which gently accompany the winds; and not least of all the grand and climactic ending. It is a fitting way to begin the recital. The Schumann is far different than I expected: Richter’s approach is understated. The pianist, known for his bombastic way in certain works—the Prokofiev Fifth Concerto for example!—plays not the passionate aspects of this work to the fullest, but rather the poetic, idyllic ones. Does Muti or the Vienna Philharmonic have something to do with this approach? Perhaps, though at times I miss the more aggressive aspects of this concerto, especially in the orchestral parts. The Vienna players have a suaveness to them, a beautiful flowing sound—they understand the inherent drama in this music, perhaps because they perform so very many operas—though they are a little less grand in this concerto than, for example, the Berlin Philharmonic under Abbado in Perahia’s recording (Sony 64577). The tempo chosen for the Intermezzo works well in this performance. Again they capture the spirit of the music perfectly. The outer sections are playful, even effervescent in effect, while the central portion’s transparent sound—the vibrato used by the strings adds a special glow to this section—contrasts beautifully with the more lively sections, which frame it. The finale is a bit sluggish at its opening, though the artists push the tempo throughout the movement. Richter’s passagework is crisp and clean; it sparkles at its best. The opening of the Mozart is tender in effect. It is obvious that these players love the work. The soloists in particular seem to breathe every phrase and feel every pause together. And though they play it in a very 19th-century way, sounding a bit heavy in certain places—over the years my ears have become more attuned to the lighter period-practice sound—this is one of those works that can take this type of treatment. The Andante is a bit slower than the norm (anywhere from 0:30 to about 1:00 slower than Perlman/Zukerman, Mutter/Bashmet, or Dumay/Caussé) though the tempo never drags. Remarkably the Vienna Philharmonic knows just when to pull back, creating a cushion of sound on top of which the soloists can gently place their material. The finale provides that necessary breath of fresh air after the two serious movements that it follows. The orchestra is as light here as they were in the Rossini—amazing how consistent their sound can remain after a few years!

Whether one is interested in Muti, in Richter, in the Vienna Philharmonic, in the two phenomenal soloists Hetzel and Streng, in Mozart, Schumann, or Rossini (and how can’t one be in at least one of them?), this is a recording you’ll want in your collection. The energy that each of these phenomenal musicians brings is palpable. The excellent recorded sound, the tiniest amount of audience noise, and the very fine program notes all add to the overall enjoyment of this disc. Grab it and enjoy! Discs like this don’t come around that often.