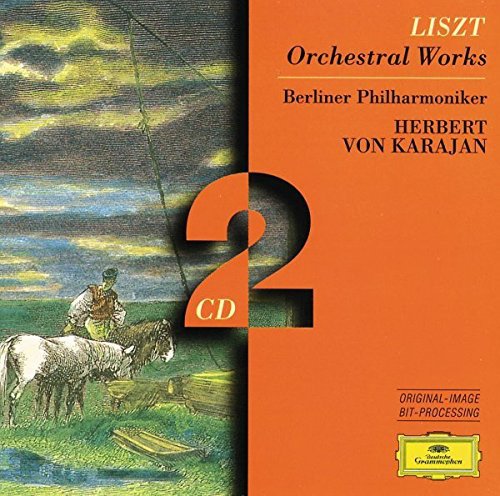

Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, Shura Cherkassky - Liszt: Orchestral Works (1998)

Artist: Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, Shura Cherkassky

Title: Liszt: Orchestral Works

Year Of Release: 1998

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:01:11

Total Size: 560 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Liszt: Orchestral Works

Year Of Release: 1998

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:01:11

Total Size: 560 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

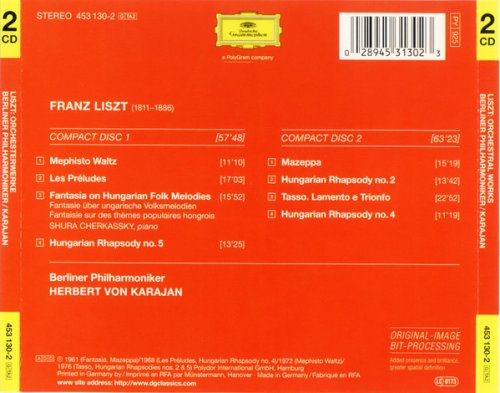

CD 1

01. Mephisto Waltz: 2. Dance at the Village Inn, from "Two Episodes from Lenau's Faust" [11:18]

02. Les Préludes, Symphonic Poem no. 3 [17:07]

03. Fantasia on Hungarian Folk Melodies, for piano and orchestra [15:58]

04. Hungarian Rhapsody no. 5 [13:25]

CD 2

01. Mazeppa, Symphonic Poem no. 6 [15:25]

02. Hungarian Rhapsody no. 2 [13:45]

03. Tasso, Lamento e Trionfo, Symphonic Poem no. 2 [22:54]

04. Hungarian Rhapsody no. 4 [11:19]

Just as Haydn is often called the "father of the symphony", so Franz Liszt is usually credited with the invention of the orchestral tone-poem. Like most simple statements about music history, however, this one probably needs some qualification. Programme music – instrumental music seeking to convey a meaning that is literary or visual – goes back as far as ancient Greece and the Pythic Nome of 586 BC depicting a fight between Apollo and a dragon. In the 16th century more instrumental "battles" were portrayed by Clément Jannequin in France and William Byrd in England, while later still, to give another example, Beethoven composed a piece called Wellington's Victory. So Liszt was hardly breaking new ground when he depicted his hero's "Struggles and Victory" in the final section of his Les Préludes in 1848. Still, it was Liszt who gave the symphonic tone-poem – a poem in sound instead of words – its full musical status, in a series of orchestral works composed between 1848 and 1882; and it was he too who first used the name, in German Symphonische Dichtung, applying it to Tasso in 1854. Les Préludes is the best known of these works, and takes its inspiration from a poem by Lamartine. In his preface to the music Liszt asked: "What is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown song of which death sounds the first solemn note?" The four sections of this music evoke different stages of life, and are linked thematically so that we hear the music as a single movement consisting of four contrasting mood-sections. The very first three notes (C falling to B and then rising to E) signal the main theme or motto, which is subsequently heard in various transformations. The first, marked maestoso (majestic), is called "Spring and Love"; then comes the wilder "Storms of Life". Gradually the music calms to a pastoral mood for "Consolations of Nature", in which the theme is given out in gentle woodwind solos, and, finally, "Struggles and Victory" has a martial trumpet version. Melodious and rousing by turns, Les Préludes, which was among the composer's first purely orchestral works, surely deserves its great and lasting popularity.

Tasso had a double inspiration. Liszt directed the orchestra at the German city of Weimar where the great writer Goethe had lived for over half a century and died in 1832. For a Goethe centenary, on 28 August 1849, he composed an overture to the play Torquato Tasso; later he revised and added to this music and conducted the final version in 1854. The subtitle is "Lament and Triumph" and the music portrays the life of the historical Tasso, an unstable but brilliant Italian poet (1544–95). Liszt, who acknowledged the influence not only of Goethe but also of Byron's poem on Tasso, begins this work darkly; then the slow music gives way to an Allegro that is no happier in mood and reflects the poet's sufferings "at the hands of the Italian princes who did not understand his genius". Some sort of transition to the triumphal section was needed, as Liszt realized when making his revision, and this is a minuet introduced by two solo cellos. After a further section depicting the poet's troubles (he actually died in custody after a knife brawl at a banquet), the final grandiose section suggests his well-earned posthumous fame and the victory of genius over adversity.

The remaining works in this set are all arrangements by the composer of music which he originally wrote for piano. Mazeppa, the sixth of his symphonic poems, derives from a famous "transcendental study" for piano, and indeed the story seems to have been attached later with suitable modifications to the music. It tells of a young Polish nobleman (honoured in poems by Byron and Hugo) who paid for an illicit love affair by being tied to a wild horse which galloped madly into the Ukraine. When it finally collapsed after many days, Mazeppa was rescued by Cossacks of whom he in time became the chief. The galloping horse is depicted with much skill, with varying versions of a D minor theme heard after the furiously rushing introduction. A quieter episode (cor anglais, trumpets) evokes the hero's loneliness, while the story's happy outcome is suggested by the triumphal march near the end of the piece.

The Hungarian Rhapsodies nos. 2, 4 and 5 are orchestral versions of the twelfth, second and fifth, respectively, of his piano series with the same title. No. 2 is initially marked "mesto" (sad) but quite soon abandons that emotion. No. 4 is the celebrated piece that begins in slow gypsy fashion but moves on to a rousing conclusion; and the Heroide-Elegiaque (no. 5) is a dignified funeral march.

Finally the Mephisto Waltz, subtitled "Dance at the Village Inn", tells a Faust story. The hero and his supernatural guide Mephistopheles listen to the dance music at a country inn. When Mephisto himself takes up the fiddle the dance becomes wild and feverish, and at the end, as a nightingale sings, Faust and the innkeeper's daughter vanish into the darkness outside.

The Fantasia on Hungarian Folk Melodies (to give it its full title) is an extended version for piano and orchestra of Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody no. 14 for piano solo, and dates from 1852. As well as a section in A minor marked "in gypsy style" (alla zingarese), the music makes much use of a tune called Mohac's Field, with a long-short-short-long rhythm: towards the end of the work it returns (Allegro eroico) in a broad and triumphant form.

Tasso had a double inspiration. Liszt directed the orchestra at the German city of Weimar where the great writer Goethe had lived for over half a century and died in 1832. For a Goethe centenary, on 28 August 1849, he composed an overture to the play Torquato Tasso; later he revised and added to this music and conducted the final version in 1854. The subtitle is "Lament and Triumph" and the music portrays the life of the historical Tasso, an unstable but brilliant Italian poet (1544–95). Liszt, who acknowledged the influence not only of Goethe but also of Byron's poem on Tasso, begins this work darkly; then the slow music gives way to an Allegro that is no happier in mood and reflects the poet's sufferings "at the hands of the Italian princes who did not understand his genius". Some sort of transition to the triumphal section was needed, as Liszt realized when making his revision, and this is a minuet introduced by two solo cellos. After a further section depicting the poet's troubles (he actually died in custody after a knife brawl at a banquet), the final grandiose section suggests his well-earned posthumous fame and the victory of genius over adversity.

The remaining works in this set are all arrangements by the composer of music which he originally wrote for piano. Mazeppa, the sixth of his symphonic poems, derives from a famous "transcendental study" for piano, and indeed the story seems to have been attached later with suitable modifications to the music. It tells of a young Polish nobleman (honoured in poems by Byron and Hugo) who paid for an illicit love affair by being tied to a wild horse which galloped madly into the Ukraine. When it finally collapsed after many days, Mazeppa was rescued by Cossacks of whom he in time became the chief. The galloping horse is depicted with much skill, with varying versions of a D minor theme heard after the furiously rushing introduction. A quieter episode (cor anglais, trumpets) evokes the hero's loneliness, while the story's happy outcome is suggested by the triumphal march near the end of the piece.

The Hungarian Rhapsodies nos. 2, 4 and 5 are orchestral versions of the twelfth, second and fifth, respectively, of his piano series with the same title. No. 2 is initially marked "mesto" (sad) but quite soon abandons that emotion. No. 4 is the celebrated piece that begins in slow gypsy fashion but moves on to a rousing conclusion; and the Heroide-Elegiaque (no. 5) is a dignified funeral march.

Finally the Mephisto Waltz, subtitled "Dance at the Village Inn", tells a Faust story. The hero and his supernatural guide Mephistopheles listen to the dance music at a country inn. When Mephisto himself takes up the fiddle the dance becomes wild and feverish, and at the end, as a nightingale sings, Faust and the innkeeper's daughter vanish into the darkness outside.

The Fantasia on Hungarian Folk Melodies (to give it its full title) is an extended version for piano and orchestra of Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody no. 14 for piano solo, and dates from 1852. As well as a section in A minor marked "in gypsy style" (alla zingarese), the music makes much use of a tune called Mohac's Field, with a long-short-short-long rhythm: towards the end of the work it returns (Allegro eroico) in a broad and triumphant form.

Download Link Isra.Cloud

Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, Shura Cherkassky - Liszt: Orchestral Works (1998)

My blog

Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, Shura Cherkassky - Liszt: Orchestral Works (1998)

My blog

![Posey Royale - The Real Low-Down (2025) [Hi-Res] Posey Royale - The Real Low-Down (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765494723_zbd6vfngwwskb_600.jpg)