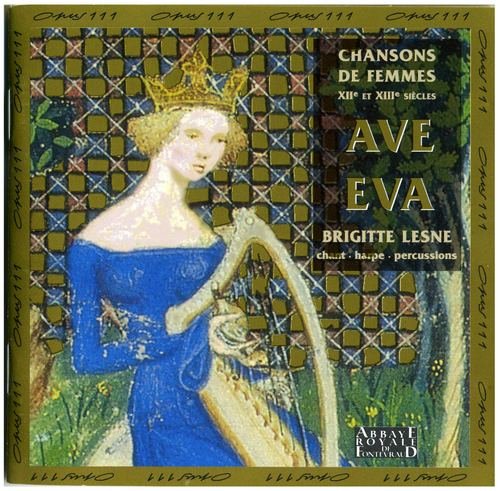

Brigitte Lesne - Ave Eva (1995)

Artist: Brigitte Lesne

Title: Ave Eva

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Opus 111

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:00:49

Total Size: 280 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Ave Eva

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Opus 111

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:00:49

Total Size: 280 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

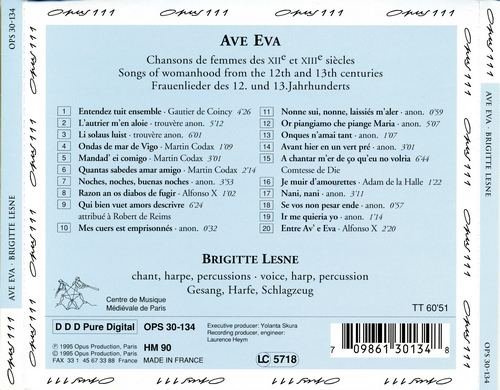

1. Entendez Uit Ensemble 4:26

2. L'autrier M'en Aloie 5:12

3. Li Solaus Luist Et Clers Et Biaus 6:01

4. Ondas de Mar de Vigo, Cantiga de Amigo (music Missing) 1:09

5. Mandad' Ei Comigo, Cantiga For Voice And Accompaniment 3:01

6. Quantas Sabedes Amare Amigo, Cantiga For Voice And Accompaniment 2:14

7. Noches, Noches, Buenas Noches, Sephardic Chanson 3:53

8. Cantiga de Santa María 109, Razon An Os Diabos de Fogir 1:02

9. Qui Bien Vuet Amors Descrivre 6:24

10. Mes Cuers Est Emprisonnés, Rondeau 0:32

11. Nonne Sui, Nonne, Laissiés M'aler 0:59

12. Or Piangiamo Che Piange Maria (Lauda) 5:07

13. Onques N' Amai Tant Con Je Fui Amée 1:07

14. Avant Hier En Un Vert Pre, Chanson de Malmariée 3:01

15. A Chantar M'er de So Qu'en No Volria, Song 6:44

16. Je Muir, Je Muir D'amourete, Rondeau For 3 Voices 1:22

17. Nani Nani, Sephardic Cradle Song 3:11

18. Se Vos Non Pesar Ende 0:57

19. Ir Me Quieria Yo, Sephardic Greeting Song 1:14

20. Cantiga de Santa María 60, Entre Av' E Eva 2:20

Performers:

Harp, Percussion, Voice – Brigitte Lesne

The Cultural Landscapes of medieval society sometimes cause people today to be afflicted with a sort of semi-blindness. The so-called 'dark ages' seem to be covered in a layer of fog which is occasionally pierced by deeds of chivalry, infinite wars, countless heresies, the Inquisition - a very masculine world.

But there is another side to this universe, that of a gigantic matriarchy as evidenced by the manifold faces of medieval womanhood. With Queen Isolde 'ki muert pour amours fine' (Lai d'Yseut), the Virgin crying out at the foot of the Cross 'al cor venuto m'e si grande cotello' (Or piangiamo) and the nun confessing in her cell that 'de riens ne mi plaist tel vie a demener' (Nonne sui), the poems reflect many aspects of femininity in medieval civilisation.

When seeking out the long-lost medieval woman, one must take into account one of the key concepts of medieval literature, that of fin'amor, courtly love. The question is, did this code of poetic communication amount to anything more than a stylistic convention? Was it a social game?

It is 'clear that everyone must strive to serve the Lady so that he can be illuminated with her grace: and she must do her best to maintain the hearts of the righteous on the paths of good deeds and honour the righteous for their merits.' Were it not for the fact that these words by Andre le Chaplain are taken from his Traite de Vamour (twelfth century), we could almost attribute their style to a sermon on the Virgin Mary. And we should not be wrong in this: in the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, an entire code of ethics was derived from this set of attitudes towards women.

In its uplifting surge, the medieval soul raised woman to the rank of a strange goddess by endowing love with an artistic, philosophic and, finally, religious dimension. The feelings of fidelity and the homage of a vassal expressed in the poetry of the troubadours and the trouveres are clothed in a codified language. A whole range of images of womankind is distilled by these poetic conventions, from scenes from pastoral life (L'autrier m'en aloie) to the avowals of women saddled with impossible husband; (Avant bier en un vert pre). The woman who is worshipped could in her turn become a worshiper, as did Queen Isolde, who sang her lay just before dying (Li solans luist) and the Countess of Die (A chantar).

The gradual transformation of this profane love into sacred - i.e. into devotion to the Virgin Mary - is a characteristic trend in thirteenth century poetry and music. Poets anxious to prove the purity of their love did not endeavour to modify their language, and simply by substituting the name of Mary for that of their lady, who was thus sanctfied and cleansed of sex, they bore witness to the common source of their inspiration. It was in this spirit of devotion to the Virgin that the trouvere Gautier de Coincy (1177-1226) dedicated his Miracles to the celestial 'Lady' and in the process creating in his work an almost inextricable puzzle of melodies and texts bound together by the general practice of borrowing from other sources. His poem Entendez tuit ensemble, for example, makes use of the melody from Perotin's well-known conductus Beata viscera.

When King Alfonso X of Castille (1221-1284), known as 'the Wise', set about collecting and copying the Cantigas de Santa Maria, it was his intention to set himself up as the troubadour of Our Lady. The celestial protectress in these poems, which are written in Galician (Entre Av'e Eva, Razon an os diabos de fugir), brings help to lost souls, saves young maidens who have suffered betrayal in love and answers the prayers of a host of picturesque characters. Beneath the shade of this 'mariarchy', there flourished during the same century a secular poetico-musical genre which was curiously similar to it, the Cantiga de amigo. Several Galician-Portuguese poems by Martin Codax (Quantas sabedes, Ondas do mar de Vigo, Mandad' ei comigo) draw back the curtain on scenes from an enclosed and refined lyrical society in which women await the return of their swains along the seashore.

There is another fundamental characteristic inherent in virtually all these different repertoires: the fact that they all spring from an oral tradition. Indeed, most of the manuscript sources available to us were compiled at a very late stage, long after the works in them came into existence. Sephardic songs (Nani, nani, Noches, noches, Ir me queria) provide an excellent example of this phenomenon. They were collected and published only recently, mostly during the course of the present century, and represent nothing more than fragments of the Judeo-Spanish world, which was scattered far and wide after the exile inflicted on Jewish communities in the thirteenth century. Although this vast repertoire did not benefit from the ministrations of copyists during the course of the Middle Ages, its language, which is close to that of the medieval poetic repertoires of the Iberian Peninsula (it should not be forgotten that the court of King Alfonso X was a cultural and artistic meeting-ground for Christian, Muslim and Jewish scholars) remained remarkably stable. Such stability is typical of all traditions that are handed down by word of mouth in civilisations in which the voice is the medium for the transmission of cultural identity, the messenger of power and the incarnation of memory.

But there is another side to this universe, that of a gigantic matriarchy as evidenced by the manifold faces of medieval womanhood. With Queen Isolde 'ki muert pour amours fine' (Lai d'Yseut), the Virgin crying out at the foot of the Cross 'al cor venuto m'e si grande cotello' (Or piangiamo) and the nun confessing in her cell that 'de riens ne mi plaist tel vie a demener' (Nonne sui), the poems reflect many aspects of femininity in medieval civilisation.

When seeking out the long-lost medieval woman, one must take into account one of the key concepts of medieval literature, that of fin'amor, courtly love. The question is, did this code of poetic communication amount to anything more than a stylistic convention? Was it a social game?

It is 'clear that everyone must strive to serve the Lady so that he can be illuminated with her grace: and she must do her best to maintain the hearts of the righteous on the paths of good deeds and honour the righteous for their merits.' Were it not for the fact that these words by Andre le Chaplain are taken from his Traite de Vamour (twelfth century), we could almost attribute their style to a sermon on the Virgin Mary. And we should not be wrong in this: in the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, an entire code of ethics was derived from this set of attitudes towards women.

In its uplifting surge, the medieval soul raised woman to the rank of a strange goddess by endowing love with an artistic, philosophic and, finally, religious dimension. The feelings of fidelity and the homage of a vassal expressed in the poetry of the troubadours and the trouveres are clothed in a codified language. A whole range of images of womankind is distilled by these poetic conventions, from scenes from pastoral life (L'autrier m'en aloie) to the avowals of women saddled with impossible husband; (Avant bier en un vert pre). The woman who is worshipped could in her turn become a worshiper, as did Queen Isolde, who sang her lay just before dying (Li solans luist) and the Countess of Die (A chantar).

The gradual transformation of this profane love into sacred - i.e. into devotion to the Virgin Mary - is a characteristic trend in thirteenth century poetry and music. Poets anxious to prove the purity of their love did not endeavour to modify their language, and simply by substituting the name of Mary for that of their lady, who was thus sanctfied and cleansed of sex, they bore witness to the common source of their inspiration. It was in this spirit of devotion to the Virgin that the trouvere Gautier de Coincy (1177-1226) dedicated his Miracles to the celestial 'Lady' and in the process creating in his work an almost inextricable puzzle of melodies and texts bound together by the general practice of borrowing from other sources. His poem Entendez tuit ensemble, for example, makes use of the melody from Perotin's well-known conductus Beata viscera.

When King Alfonso X of Castille (1221-1284), known as 'the Wise', set about collecting and copying the Cantigas de Santa Maria, it was his intention to set himself up as the troubadour of Our Lady. The celestial protectress in these poems, which are written in Galician (Entre Av'e Eva, Razon an os diabos de fugir), brings help to lost souls, saves young maidens who have suffered betrayal in love and answers the prayers of a host of picturesque characters. Beneath the shade of this 'mariarchy', there flourished during the same century a secular poetico-musical genre which was curiously similar to it, the Cantiga de amigo. Several Galician-Portuguese poems by Martin Codax (Quantas sabedes, Ondas do mar de Vigo, Mandad' ei comigo) draw back the curtain on scenes from an enclosed and refined lyrical society in which women await the return of their swains along the seashore.

There is another fundamental characteristic inherent in virtually all these different repertoires: the fact that they all spring from an oral tradition. Indeed, most of the manuscript sources available to us were compiled at a very late stage, long after the works in them came into existence. Sephardic songs (Nani, nani, Noches, noches, Ir me queria) provide an excellent example of this phenomenon. They were collected and published only recently, mostly during the course of the present century, and represent nothing more than fragments of the Judeo-Spanish world, which was scattered far and wide after the exile inflicted on Jewish communities in the thirteenth century. Although this vast repertoire did not benefit from the ministrations of copyists during the course of the Middle Ages, its language, which is close to that of the medieval poetic repertoires of the Iberian Peninsula (it should not be forgotten that the court of King Alfonso X was a cultural and artistic meeting-ground for Christian, Muslim and Jewish scholars) remained remarkably stable. Such stability is typical of all traditions that are handed down by word of mouth in civilisations in which the voice is the medium for the transmission of cultural identity, the messenger of power and the incarnation of memory.

![Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip] Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771860317_5.jpg)

![The Messthetics & James Brandon Lewis - Deface The Currency (2026) [Hi-Res] The Messthetics & James Brandon Lewis - Deface The Currency (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771424652_1.jpg)